DNA Damage Differences in Non-Smokers Exposed to ETS

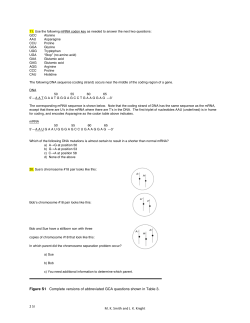

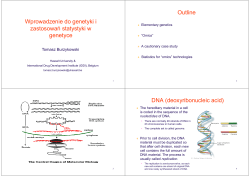

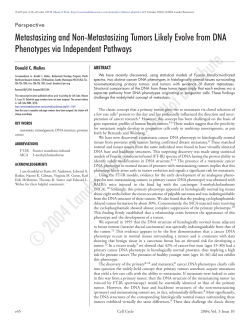

ffi ELSEVIER Availableonline at www.sciencedirect.com acrE ""= @DrREcro Toxicology Letters ToxicologyLetters158 (2005) I 0-19 www.elsevier.com/locate/toxlet Differencesin DNA-damagein non-smokingmen and women exposedto environmental tobaccosmoke(ETS) Abby C. Collier8,c,SachinD. Dandgeb,JamesE. Woodrowa,c, ChrisA. Pritsos&'c'* u Department of Nutrilion, University of Nevada, 1664 N l4rginia/MS I42, Reno, NV Bg557, USA b Department of Biochemistry, University of Nevada, Reno, NV gg557, USA c Environmental Sciencesand Health Program,lJniversity of Nevatla, Reno, NV BgSS7,USA Received29 December 2004; receivedin revisedform l0 February2005; acceptedI I February 2005 Available online 24Mav 2005 Abstract There is much data implicating environmentaltobaccosmoke(ETS) in the developmentand progressionof disease,notably cancer,yet the mechanismsfor this remain unclear.As ETS is both a pro-oxidant stressorand carcinogen,we investigatedthe relationshipof ETS exposureto intracellular and serum levels of DNA-damage, both oxidative 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8OHdG) and general,in non-smokersfrom non-smokinghouseholds,occupationallyexposedto ETS. GeneralDNA-damage consistingof singleand doublestrandbreaks,alkali-labilesitesand incompletebase-excision repair,increasedsignificantlyin a d o s e - d e p e n d e n t m a n n e r w i t h E T S e x p o s u r e i n m e n ( P : 0 .n0:135l ,,P e a r s o n ) b u t n o t w o m e n( P : 0 . 7 3 6 , n = 1 7 ) . l n t r a c e l l u l a r SOHdG-DNA-damage and generalDNA-damagewere both greaterin men than women (P:0.0005 and 0.016,respectively) but SOHdG seru-nlevels did not differ betweenthe genders.Neither 8OHdG-DNA-damagenor serum levels correlatedwith increasingETS exposure.This is the first studyto demonstrate dose-dependent increasesin DNA-damagefrom workplaceETS exposure.Perhapsmost interestingwas that despiteequivalentETS exposure,significantlygreaterDNA-damageotcurred in men thanwomen. Thesedatamay begin to providea mechanisticrationalefor the generallyhigher incidenceof some diseases in malesdue to tobaccosmokeand/orothergenotoxicstressors. O 2005 ElsevierIrelandLtd. All rights reserved. Keyv'ords:Environmental tobaccosmoke;DNA-damage; DNA repair;8-Hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine Abbreviatiorts.' 8olJdG, B-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine;ELISA, enzyme-limited immuno sorbent assay;ETS, environmentaltobacco smoke; Fpg, formamidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase;HPLC/ECD, high pressureliquid chromatographywith electro coulometric detection;hoGGl, human8-oxoguanineDNA glycosylase " C o r r e s p o n d i nagu t h o r T . e l . :+ l 7 7 5 3 2 7 5 0 9 5 ;f a x : + l 7 7 5 7 9 4 l l 4 Z . E-rttailoddresses. [email protected] (A.C. Collier), [email protected] (C.A. pritsos). 0378-4214ts seefront mattero 2005 Elsevierlreland Ltd. All rishts reserved. d o i :I 0 .I 0 I 6 / i . t o x 1 e t . 2 0 0 5 . 0 2 . 0 0 5 A.C. Collier et al. / Toxicologt Letters I 5S (2005) t 0-t 9 1. Introduction Recently,non-smoking areas in bars and sports clubshavebeenshownto providelittle or no protection for patrons(Cains et al., 2004), corroboratinganecdotal medicalreportsand previousstudiescontending that legislationis themosteffectivetool to reduceenvironmentaltobaccosmoke (ETS) exposureand smoking behaviour(l{eloma et a1.,2001).While ETS exposurehas been linked to a number of disorderssuch as asthma,intra-uterinegrowth restriction,suddeninfant deathsyndrorneand coronaryheartdisease,it has beenmost consistentlyand strongly implicatedin the initiationandprogressionof cancer(Anon, 1996).Despitethis, the temporalrelationshipsand mechanisms by which cigarettesmoke causesinitiation and progressionof diseaserernainsrelatively unknown. Furthermore,althoughsocial ETS exposureis relatively controllable(an individual may choosenot to enter premisesw,heresmokersarepresent),employeeshave little or no inffuenceover ETS and may be exposedfor a largepart of their working day. Havingpreviouslyidentifiedsignificantlyhigher8hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8OHdG) levels in nonsmokingworkersoccupationallyexposedto ETS compared to non-smokingworkers who are not exposed to ETS (Howarcict al., 1998),the goal of this study wasto assess a quantitativerelationshipbetweenDNAdamageand workplaceETS exposure,and to investigate the contributionof the oxidative DNA lesion 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8OHdG) to total ETSinducedDNA-darnagein the blood of non-smokers. Differencesin DNA-darnagewith respectto SOHdG werealsoassessed in relationto ETS exposureand demographicvariables. 2. llethods 2.L Par"ticipcutts rurclrecruitment Non-smokers,living in non-smokinghouseholds who work at casiuosand bars in Reno and Las Vegas,NV were recrLlitedfor the NevadaEnvironmental TobaccoSrnokeStudy(NETSS).Fifty baselineblood samplesfiorn NETSS were randomly selectedfor the currentstudy.All parlicipantsprovidedinformedconsentandthestudywereapprovedby theBiomedicalIn- ll stitutional Review Board at the University of Nevada, Reno. Participantdemographicsand baselinecharacteristicsare shownin Table l. 2.2. Cotinine analvsis Cotinine levels were determined to verify selfreportednon-smokingstatusand to quantitateETS exposure.Plasmasamples,I mL from NETSS filtered throughOasis@MCX (Waters,Milford, MA) cationexchangesolid phase extractioncartridgesand cotinine elutedprior to GC/lvIS analysis,as describedin the Product Insert. Briefly, acidified plasma samples (0.05meq HCI) were filtered through separateprepared cation-exchangecartridges,washed with 2 mL 0.1M HCI then 2mL methanol and cotinine eluted with 1.5mL ammoniumhydroxide(5% in methanol). Eluateswere vacuumedto dryness,60"C (l h), redissolvedin 0.2 mL ethyl acetateand filteredthrough 0.45 pm membranefilters into autosampler vials.Samples were chromatographed on an Agilent 6890 plus gas chromatograph(San Femando, CA) and detected with an Agilent 5973N mass spectrometeroperating in selectedion mode (EI: 70 eV). An aliquot (2 p"L) of each sample was injected onto a 30 x 0.25mm (i.d.) DB5-MS fusedsilica opentubularcolumn(J&W Scientific) and chromatogramsdevelopedusing the following GC/MSD program: 60"C (lmin), rhen 25"lmrn to 300"C (hold I min); a post-runhold of l0min at 300oC was imposedafter eachsample(total run time : 21.6min). Cleansolventinjectionswere made betweenstandardand sampleinjections to minimize carry over of the cotinine analyte.The fragment at mlz:98.1 was used for quantitation,and retention time for the cotinine analytewas 7.68min. Averagerecovery from clean, spiked plasma (0.3-4 ng/ml,) was 100.7+ .1.6%w i th a C V of 8.0+ 4.4% .The concentration range for the standardcurves was l-80 nglmL with limits of detectionand quantitationof 0.I nglmL and 0.3 nglmL, respectively. 2.3. Single cell gel electrophoresis(Comet)assay DNA-damage was assessedby the Comet assay in whole blood sampleswith or without inclusionof human 8-oxoguanineglycosylase(hOGGl) enzyme, which cleaves8OHdG-DNA lesionsand allows them to run under electrophoresisand thus be detected.This ll A.C. Collier et al. / Tbxicolog,,Letters I Sg (2005) l0_t g fable I Baselinedenrographics of study participantsfor the whole studypopulation and for male and femaleparticipants - ,Mv a r ol e, Lsr 33 nla 17 q88+es (2s44) nla 28'9 + 4'3 (20'4-37 '8) 29.6+.4.0 (2334;.8) Females Mea..,ro i- ctor.l.-,J ,1^,,:^+:.-- /. - ,, ffi;;::,;T,x',ilii';':,:::jfi"*) x a stanoaro deviatiorr(range) Ethnicity Caucasian Larino Asian Black/AfricanArnerican A m e r i c a nI n d i a no r A l a s k an a t i v e N a t i v eH a r v a i i a n o r o t h e rp a c i f i cI s l a n d e r other Education S o n e h i g h s c h o o t( 9 - l l y e a r s ) H i g h S c h o o dr i p r o r n o ar G'E'D' "Ti::ilij,::ffi:ilffij;:" Sornecollegeor associatedegree C o l l e g eg r a d u a t eo r B a c c a l a u r e a d r ee g r e e S o m ec o l l e g eo r 1 r r - o f e s s i o n a l schoolaftercollegegraduation M a s t e r ' sd e g r e e 26 (52%) n e2%) 2 (4%) 3 (6%) 4 $%) 2 (4%) 2 g%) | e%) n Q6%) 482t102(2s-64) 5'+ 8.4(2s_.62) g 67.6%) 7 el.z%) | Q'0%) 2 g.o%) 3 eJ%) ", 0.''' 2 6.0%) | (3.0%) 6 (r8.r%) widorvecl Presently.narried Lir''ingin a marliage-like rike relationship rerarionqhin 2g.0+ 4.g (20.4-37.7) 7 gt.2%) 4e3.5%) | 6.9%) | 69%) | 6.9%) z (ll.g%) 0 0 7 @r.2%) 602%) 3e%) 3(,76%) 22 g4%) 6 (12%) I e \-'%-/ ) n 64.s%) 4 (12.1%) 0 u 4 e3'%) 2 (ll.g%) I (5.9%) I e%) | G%) o 8(16%) s(ts.2%) Marital status ilffiil':T::pararcd u nJa ila nla 12(24%) 3(17.6%) o o 8 Q4'2%) 4 e3.s%) 24 (48%) 6 (12%) l5 g5.5%) S (15.2%) g o 62.9%) | 6.9%) }:':':::';1*['Hffij',',:u'.''n.characteristicsofage,BMI,ethnicbackground,educationleve|andmarita|.ffi wasperfbnnedr-rsing a commerciallyavairableFlareTM assaykit (Trevigen,Gaithersburg, MD) asper the manufacturer'sinstructions. Briefly,ceilswereplatedin low meltingpoint agarose,slideswere lysedand DNA un_ windingoccurrcclfbr l h at pH >13. Slideswere elec_ trophoresedfor 30 min (0.g5V/cm) and dried down beforestainingwith SyBR greenTMand visualization usinga ffuorescent microscopeat 400x magnification. Threeblocldsamplesper personwere assessed and 50 cells werc scoredranclornlyby eye in eachsample, on a scaleof 0-4, basedon fluorescencebeyond th. nucleusandwerepreviouslydescribedby Kobayashi et al. ( 1995).Thescaleusedwasasfollowsr0: no cometing; I : Cornet< 0.5 times the width of nucleus;2: Co.Ji equalto width ofnucleus;3: Cometgreaterthan width of nucleus;4 : Comet> two times the width of the nu_ cleus.Scoringcellsin this mannerhasbeenshown to be as.accurate and preciseas using computerimageanal_ ysis (Kobayashiet al., 1995).The individual sclring of theslideswasblindedto anydemographicor biochJmi_ calaspectsofthe bloodsamples.GeneralDNA_damage was calculatedfrom the sampleswith no hOGGI ei_ zymeadded,while specificgOHdG-DNA-damage was calculatedby subtractinggeneral DNA_du-ugJ frorn in correspondingsamplescontainingnbCCf . 9-.T".g: Variabilitycausedspecificallyby the Cometissay pro_ cedurewas controlled by running one loading.ontrot sampleforeveryparticipant.Loading controls werenot lysedand unwound,but were electrophoresed with ex_ perimentalsamplesand developedwith ethidium bro_ mide. Every loading control was checked visually on a microscopeand a picture was taken with a Geidoc A.C. Collier et al. / Toxicologt Letters I58 (2005) 10-19 (Biorad,Hercules,CA) to ensureloading of a similar numberof white blood cellsand therebycontrolfor retardationin DNA rnigration due to over-loading.Sampleswherewhite blood cellswere overloadedwere repeated.Loadingcontrolsalsoservedto measurelevels of arlifactr"ral DNA-damagecausedby electrophoresis alone. thawed,appliedto spinfilters(10,000Mw cut-off,Millipore,Billerica,MA) and centrifugedat 12,000x g in a benchtopcentrifugefor 30 min. Flow-throughwasapplied to OXYcheckhigh sensitivitycompetitiveELISA plates(Genox,Baltimore, MD) and quantitationproceededas per the manufacturer'sinstructions. 2.5. Statistical analysesand data manipulation t, r rrr "rninat i ott oJ'BOH dG concentratio ns in /,.r,l All analyseswere performed with GraphPadprism 3.0 (GraphPadSoftware,San Diego, CA). Data analysis showedthat DNA-damageresultsapproximateda Gaussiandistribution;thus; unpairedStudent's/-tests with Welch's correction for unequal varianceswhere appropriate,linear regressionand Pearson'scorrelation and one way ANOVA with Tukey's post test were usedas detailedin Figs. I and 2 andTable2. Statistical analysiswas performed in a post hoc manner after all biochemicalanalyseswere completed. Concentrationsof SOHdG were determined in serum sarnplesdrawn from participantsat the same time as plasma and whole blood samples.Blood was drawn into a SST vacutainer,allowed to clot at room temperaturefor 45 min-l h and centrifuged at 1000rprnfor l0min. Serum was aliquotedinto cryovialsandstoredat -70 until use.Before 8OHdGconcentrationswere determinedin serum, sampleswere * 1'4i a b 1'o'i . P fi o'si r A I l r n ^-i A { 0.6j I z : l nri r8QH'JGDartageP=0.s779 A Gen€ral DNAdamage P- 0.00a! a H r"j (E "- i t O a I $ "''l I ra U t-^* i Io.ai r I I n raaa l r S:{*ri'",*': 3l $ r"; 0 1 2 3 (A) t, o A t,4 {r 1,0 $t o's * 0.6 a 0.4 d n c (B) r r tra .a^ 1.4 1.2 1.0 female I BOtjdG O;rmageP * 0.310 A 0eneral DNA clamageP= 0.716 I a ' I z ",* cl o.o aS0HctGDarrageP-0.70t A 6eneral OFiAclanragep= t).001S I r 4 s Hlosd cotinine concentration {ug/mL) male 1.4 l3 A c ItrA I 0 1 2 3 4 5 Blood cantinlne concentration (ug/ml) 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 0 1 2 3 4 5 Blood continine concentration (c) (us/ml) Fig. I Gencralbut not SOHdG-DNA-damageis significantlycorrelatedto workplaceETS exposurein the blood of male non-smokers.(A) Oxidative8OHdG (I) and generalDNA-damage(A) in the srudypopulation @:a\.(B) OxidativegOHdG lesions(l) andtotal DNA_damage (A) in malesonly (n:32). (C) Oxidative 8OHdG lesions(l) and total DNA-damage(A) in females only (n: l7). p-valuespresentedare Pearson'scorrelationcoefficients. A.C. Collier et al. / Toxicologt Letters I 5S (2005) t O-19 2g I c l S .g rA Eai- 80H2dc r = 0.9359 I s8 El; o I I I eE 6 $8; 0 (A) .b:16 I E€ t,l 39'l k r c 2 0 .g ls r 80HdG r = 0.8557 0 r UOHdG r = 0.4473 E :irs fiE gll 9to I I i sI t st 6 fie : U" {B) Fernale Male E 2 0 fr -:18 UPra 1 2 3 4 Gontinine concentralion (ng/mL) t r I { l ) 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 Contininaconcentration{ng/mL) (C) 0 1 2 3 4 5 Continine concenrration (ng/mL) Fig. 2' 80HdG levelsin the serumof non-smokersarenot correlatedto workplaceETS exposure.(A) Serum8OHdG concentrations (l) in the whole studypopulation@ - a9).(B) Serum8OHdG concentrations (I) in malesonly (n : 32). (C) Serum80HdG concentrations (I) in females o n l y( r : l 7 ) . 3. Results One participantwas excludedbecauseits cotinine value(l37ngAnl-) represented an activesmoker;subsequentstatisticalanalysis was performed with 49 individuals(32 rnenand l7 women).Analysisofthe rernainingparticipantsindicatedthat cotininelevelsdid not differ significantly between or within any demographic sub-group(Table 2). General DNA-damage in the Comet assaycorrelated significantly with increasingcotinine levels in the whole population(P:0.0042, Pearson,Fig. lA) but 8OHdG damagedid not. Further sub-groupanalyses showed that general DNA-damage increased Table2 Relationships of gencralDNA-damage,SOHdG-DNA-damage, serum8OHdG concentrations and cotinineto demographicsub-groupsin the studypopulation Non-oxidativeDNA-daurage 8OHdG-DNA-darnage 8OHdG serumconcentration Cotinine Gender (t-test) Caucasianvs. other (l-test) Latino vs. other (l-test) BMI (Pearson) Age (Pearson) Marital status (ANOVA) ** 0.0163 0.0005" 0.0707 0.4230 Education (ANOVA) 0.7531 0.7467 0.1138 0.309r 0.5282 0.98',72 0.6102 0.7028 0.6477 0.s282 0.8092 0.9276 0.8587 0.9s06 0.0289* 0s602 0.9203 0.4398 0.6002 0.6863 0.6221 0.8512 0.4846 0.3977 Note. tlte lack of sigrtificaltceof cotinine levels betu'eenor within any demographicparameters,indicating equivalent ETS exposurein this population. * P < 0.05. "'P<0.01. A.C. Collier et al. / ToxicologyLetters l5S (2005) l0-19 significantlywith ETS exposurein males but not fem a l e s( P : 0 . 0 15 , n : 3 2 , F i g . l B a n dP : 0 . 7 3 6 , n : 1 ' ,l Fig. lC respectively).The average general DNAdamagescorefor males(0.27+ 0.47)was significantly higherat t han i n fe ma l e s(0 .0 6 + 0 .0 8 , P:0 .016, rtest).In contrast,SOHdG-DNA-damagedid not correlateto increasingETS exposurein the whole population nor in eithergender(P:0.79, male; P:0.31 female, Fig. lA-C). Despitethis, the averagedamagescores for SOHdG-DNA-damagewere significantly higher in males (0.31+ 0.34) than females(0.059+ 0.I l, respectively, P: 0.0005,r-test). Concentrations of SOHdG in serumdid not correlate to ETS exposure(Fig. 2A-C) and did not differ significantlybetweenmen than women (P:0.0756). The 8OHdG levelsin serumdid correlatesignificantly with age(P:0.0289) but did not differ with any other demographicvariable(Table2). No other demographics showedsignificantdifferencesor corelations with DNA-damage(oxidativeor otherwise),SOHdGserum concentrations or cotininelevels(Table2). To eliminateconfoundingof our resultscausedby baselinemi smatching,analysisof baselinedemographics (age, body mass index, educationlevel, marital status,and ethnic background)was performed. There were no statisticallysignificantdifferencesin baseline demographicsbetween male and female participants (Table 1), strengtheningthe apparentgender-specific differencesin DNA-damage.Furthermore,althoughno samplewas thawed more than once prior to theseexperiments,we assessed whetheror not the numberof freeze-thawcyclesaffectedthe averageDNA-damage scorefrom the Cometassay.No significantrelationbetween the numbersof freeze-thaw cycles and general DNA-damageor SOHdG-DNA-damage was observed (P:0.778 and P :0.97, respectively, Pearson).In addition, although actual numbers were not recorded. DNA-damageattributedto electrophoresis in the control slideswas checkedat random and was very low with few cellsexhibitingany cometing(2-3 Comets/50 c ells ) . 4. Discussion GeneralDNA-damagein the blood of non-smoking men increasedin a dose-dependent mannerwith exposureto ETS in the workplace(P:0.015) and was l5 significantlyhigher than in women (P:0.0163). In contrast,neither oxidative 8OHdG-DNA-damagenor SOHdG concentrationsin serum correlatedwith ETS exposure.In addition,althoughSOHdG-DNA-damage levels were significantlyhigher in men than women (P:0.0005), serumconcentrations of SOHdGdid not differ betweengenders. One of the most important aspectsof this study is that cotinine levels were the same between males and females (Table 2). Cotinine also did not differ between or within any other demographic group or stratification,which is further evidencefor equivalent ETS exposureamong all the participants.Different cotinine levels may be ascribedto differentialtimes since exposure and/or genetic polymorphism in CYP2A6, althoughthis polymorphismdoesnot exist at significantlevelsin the populationsampled(yang et aL,200l). In addition,confoundingvariablesfor foodrelated nicotine levels in experimentalparticipants have been previously investigatedand cauliflower, eggplant,tomatoes,potatoes and black tea contain measurablelevelsof cotinine(Benowitz,1996).While it hasbeensuggested that the dietaryintakeof nicotine throughthesesourcescould confoundstudiesof ETS, especiallywith respectto genderbecauseof fruit and vegetablesintake (Glynn et al., 2005); using pharmacokinetic analysisand typical American vegetable consumptiondata,Benowitz(1996)placesthe average dietary nicotine intake at around to 0.7 pg daily (Benowitz,1996).Additionally,thereareno othersexrelateddifferencesin cotinine clearanceswith gender (Gries et a1.,1996).Up to 80% of a dose of nicotine is convertedto cotinine via a C-oxidation pathway, and the resultingcotininemetabolitehas a half-life of l5-I7 h. In comparison,nicotine has a much shorter half-life of 2.6h and has different clearanceratesin smokersandnon-smokers(Benowitzand.Iacob,1993; Kyerematenet al., 1990). Hence, due to its longer half-life, cotinine is readily identified in samples, which may have been drawn relatively long periods of time after ETS exposureand the methodsusedto detectand quantify it (generallyGC/MS or LCIMS) are rapid, sensitive, precise and accurate (Tricker, 2003). Another issue relating to the timing of procuring blood samplesis the rate of SOHdG-DNA lesion repair. The kinetics of hOGGI for 8OH2dG follow Michaelis-Mentenkinetics and have a V^u* of l6 A.C. Collier et al. / Toxicologi Leuers l 5B (2005) I0-19 0.51+ 0.17nM/min 8OH2dG(Asagoshiet al., 2000). Thus,at high 8OH2dGlevels,the enzymemay become saturated,indicating that the length of time from ETS exposureto DNA repair may also be dependenton the levelof exposure.Despitethis,the ftss1 forhOGGl with respectto8OH2dGis 0.034min, which is relativelyfast (Asagoshiet al.,2000).This is complicatedby a distinct sequenceaffinity of hOGGI for 8OH2dG in certain portions of the genetic code, whereby sometimesthe rateand efficiencyof hOGG I for SOHdG is alteredby thepositionon the lesion.The sameis truefor the other enzymethat removesSOH2dG,formamidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase(Fpg). This enzymehas a V^u* of 2.1+ 0.7nM and a ksil of 1.8min (resultingin similar intrinsicclearances to hOGGI) and also demonstrates a DNA-sequence specificaffinity for lesions(Asagoshi et al. ,2000) . This study was designed to determine whether a dose-dependent relationshipbetweenDNA-damage and increasingoccupationalETS exposureexists.Previous researchfrom our laboratory has demonstrated significantly higher 8OHdG levels in non-smoking workersoccupationallyexposedto ETS comparedto non-smokingworkerswho are not exposed(Howard et al., 1998),andwe wishedto follow on from this finding and investigatedose-responserelationshipsbetween levels of ETS exposureand levels of DNA-damage. It has also been shown that self-reportedETS exposure significantlyunderestimates the actual exposure of studyparticipantsto ETS (Delorenze et a1.,2002) and that ethnicity, marital status, education and age (Iribanen et al., 2004; Kurtz et al., 2003; Reynolds et al.,2004;SolimanetaL.,2004)canaffectexposurelevels.In ordertoaddressthis,thecurrentstudyusedblood cotininelevelsas a marker of ETS exposurenot selfreporting,andthe datapresentedin Table2 demonstrate that no significantdifferencesin cotinine levelswere observedbetweenor within these demographicsubgroups.This indicatesthat our findingsarenot skewed by mismatchingbetweenmales and females and further,that the measuredETS exposureis likely to comprise almost exclusivelyof workplace ETS exposure and not exposurethrough the home (often correlated with marital status(Kurtz et al. 2003; Reynolds et al. 2004)) or social exposure(often correlatedwith age (Reynoldset al., 2004)). Although previous studies have reported higher 8OHdGin smokersthannon-smokers(Loft et al., IggZ) and for workers in smoking comparedto smoke-free workplaces(Howard et al., l99B), dose-dependent effectsof ETS on either 8OHdG lesionsor other forms of DNA-damagehave not been reportedin humans.It hasbeenshownby HPLC with electro-chemical detection methodthat SOHdG-DNAlesionsaresignificantly higher in pooled male blood samplesthan pooled female blood samples,and that large geographicaldifferencesin damagelevelsoccur (Collins et al., 1998). Our study is in agreementwith thesefindings regarding the gender-differencesin SOHdG-DNA adducts. althoughall of our sampleswere from a similar geographicregion.Becausewe employeda Comet assay approach,individual blood samplescould be assessed (blood volume is the limiting factor for HPLCiECD analysis),therebyincreasingthe power of the experiment.The advantages of usingthe Cometassayinclude the small number of cells required,the high sensitivity of the procedure(DNA-damagecausedby <5 cGy gammarays canbe observed)and the economical,fast and simplenatureof the assay(Rojaset al., 1999).The disadvantages of the Comet assayas it was usedhere mostly relate to technicalvariability in scoringcells and interpretationof results and the sample sizesper assay,which havebeencriticisedfor causingsampling bias.Theseconcernsare somewhatmitigatedby having all of the cell scoringperformedby onepersonand scoring large numbersof cells (50 cells per determination,in triplicate)(Kobayashiet al., 1995;Rojaset al., 1999).In addition,samplingbias relatesmore to solid tissueswhere resultsmay be skewedby regionspecificdifferencesin DNA-damage.In a circulating tissuesuchasblood,regio-specificityin DNA-damage is lesslikely to be observedand unlikely to havebeen a factor in this study. Finally, our manner of scoring cells usingthe 0-4 scaleand assessing damageby eye has beenshownby previousinvestigatorsto be as accurate,more sensitiveand fasterthan computerimage analysisand to correlatealmostexactlywith computertzed analysesof ratio (DNA% in tail) and tail moment (productofratio andtail distance)whengradedconcentrations of known DNA damaging agentswere tested and scoredby doubleblinded investigators(Kobayashi et al ., 1995). Sincemost ofthe damagecausedby cigarettesmoke is believedto occur through DNA adducts,the power of the Comet assayin detectingDNA-damagecaused by smokingand/orETS hasbeenquestioneddueto the A.C. Collier et al. / ToxicologyLetters l5B (2005) l0-19 fact that DNA crosslinks and adductsretardthe migration in the assay(Sram et al., 1998).Theseproperties of DNA migrationunder electrophoresis are likely to be responsible, at leastin paft, for many conflictingreportson DNA-damagecausedby cigarettesmokewhen the Comet assaywas used as the only form of analysis and may be accountablefor the resultsof the lone studywhere Comet assaysreportedlessDNA-damage in smokersthan non-smokers(Speit et a1.,2003).The pH of DNA unwinding and electrophoresisand the lengthof time unwinding and electrophoresis are performed are also critical to the amount of cometing observed.For example,as pH increasesso do the amount and typesof DNA-damagedetected.Therefore,differencesin DNA-damagereportedby different laboratories could be due to variancein the pH of DNA unwinding and/orrunning buffers. In the presentstudies, as well as using an enzymeto cleaveDNA at 8OHdGadductssites and comparing theseresultsto assaysin the same participantswhere enzyme was not added, unwindingwas carriedout at pH >13 where the assay detectsthe most possibleforms of DNA-damage.Additionally,as discussedabove,our use of loadingand running controlsenabledchangesin DNA migration dueto the numberof cellsloadedand cometingcaused by themethoditselftobe eliminatedasvariables.Moreover,becauseSYBR greenTMwas usedas the detector fluorophore,the assayis extremelysensitive.This is importantas a recent investigationof differencesin DNA-damagebetweensmokersand non-smokersusing ethidiumbromideasa fluorophorereportedthatdetectionof smoke-induced DNA-damagewas limited in the Cometassay(Sramet al., 1998).When comparing fluorophores, ethidiumbromideshows3O-foldfluorescenceenhancement uponbindingto DNA while SYBR greenrMexhibits1000-foldfluorescence enhancement (MolecularProbes,2004\. Despite equivalentworkplace ETS exposure,both intracellular 8OHdG and general DNA-damage were greaterin males than females,but there were no significantdifferencesbetweenmen and women in serum levelsof extracellular(repaired)8OHdG. Some caution is neededin interpretingtheseresultsbecauseit is possiblethat if theseexperimentswere expandedto a largerpopulation,differencesin extracellularSOHdG serum concentrationsbetween the men and women would becomesignificant,asthe P-valuebetweenmen and women in the current study was low (0.07). In t7 addition,when discussingaspectsof DNA repair in this study,it is important to note that DNA repair was not measureddirectly, thus attributing differencesbetween DNA-bound 8OHdG lesions and free plasma SOHdG to repair remainsa hypothesismeaningthat concreteconclusionsregarding gender-relateddifferencesin DNA repair are difficult to substantiatewithin the sizeandpower of this study.Despitethis, thesedata may indicate gender-differencesin DNA-damage and repair capacityand speculativelyprovide a rationale for the higher incidencesof somesyndromes(notably most cancersand heartdisease)in malescomparedto females(Manton, 2000). Although women are more susceptibleto certain forms of cancersuch as cancers of the breast,these cancersare predominantlyhormonal and not mechanisticallygenotoxic(Wingo et a1.,2003).Inaddition,althoughwomen haveovertaken men with respectto incidenceof lung cancerssincethe 1980s,this has largely been attributedto behavioural and social factorsnot biochemicalor cellular events (Levi et al., 2004; Wingo et al., 2003). For cancers where initiation is predominantlythrough genotoxic and mutagenicmeans,such as liver, gastro-intestinal, bladderand colo-rectalcancers,epidemiologicalstudies have uniformly reportedgreaterincidencesin men thanwomenin both EuropeandUSA overthe lastcentury (Levi et al., 2004;Manton, 2000 p. I l; Wingo et al., 2003).Recentresearchhas demonstrated a constitutive polymorphismof the hOGGI genethat results in reducedability to repair SOHdGlesions.This polymorphism is also associatedwith higher lung cancer risk (Park et al., 2004).Also, Gackowskiet al. (2003) have reportedthat levelsof 8OHdG in DNA isolated blood of lung cancerpatientswas significantlyhigher than that in DNA isolated from healthy smokersand non-smokers(Gackowskiet a1.,2003).Itis, therefore, possiblethat data presentedshowing higher BOHdG lesionsin the blood of men exposedto ETS may be associated with lung cancerrisk. The distinction between excisedbasesand intracellular,bound DNA-damage is particularly important in terms of long-termaffectson homeostasis, cell cycling and the developmentof disease.For example, incompletebase-excisionrepair sites,which are detected in nuclear DNA by the Comet assayand likely make up some of the generalDNA-damage observed here, frequently leads to inappropriatetranscription, cell cycling and metastasis(Gantt et al., l986). It is l8 A.C. Collier et al. / TbxicologyLetters 155(2005) l0-19 difficult to say preciselyhow detrimentalthe general DNA-damagedetectedhereinwill be in the long-term becausedouble and single strandbreaks,incomplete base-excision repair sitesand alkali-labilesitesare all detectedby the Comet assay,but their relativefrequenciesin the presentstudy are unknown. In contrast,a direct measureof the amount of 8OHdG-DNA-damage was measuredand the amount of SOHdG in serum (which is more indicativeof DNA repair capacity)was also measuredproviding a direct gaugeof repair capacity. ETS is known to be a carcinogen,pro-oxidantstressor and genotoxicagent.Here we haveshown a significant,positivecorrelationof greaterDNA-damagewith increasingETS exposure.A directcorrelationbetween ETS exposureandnon-8OHdGdamagewould be even more conclusivein the presenceof either a control group(suchasnon-smokers not exposedto ETS) showing a lack of suchcorrelationor in a longitudinalgroup showing increasingDNA-damage levels with time. However,perhapsthe most interestingfinding was the gender-specific differencesin DNA-damageand potential differencesin repair observed.These results provide a "snapshot" of the interplay betweenDNAdamageand ETS exposure,and along with other recent findings, further evidencethat gene-environment interactionsof DNA repair enzymes may be important in cancerrisk and mutagensensitivity(Ito et al., 2004; Tuimala et al., 2002). The dose-dependency observedfor generalDNA-damage and ETS, suggestsa dynamic equilibrium betweendamageand repair with respectto ETS exposureovertime, while discrepancies betweenhigher levels of intracellularDNA-damage (both general and 8OHdG) in men than women but comparableamountsof (repaired)serum8OHdG, may imply genderdisparitiesin the expressionand activity of DNA repair enzymes.This study may provide insight into the genotoxic, mutagenic and carcinogenicmechanismsof ETS and also may also help explain gender-differences in the susceptibilityto cancer and other diseasescausedor exacerbatedby tobacco smoke. Acknowledgement Funding for this project was supplied by NIEHS grantnumberES09520. References Anon, 1996.Cigarettesmokingand health.Am. J. Respir.Crit. Care M e d . 1 5 3 ,8 6 1 - 8 6 5 . Asagoshi,K., Yamada,T., Terato,H., Ohyama,Y., Monden,y., Arai, T., Nishimura,S., Aburatani,H., Lindahl, T., Ide, H.,2000. Distinct repairactivitiesof human 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase and formamidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase for formamidopyrimidine and 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine.J. Biol. Chem.275,49564964. Benowitz,N., 1996.Cotinine as a biomarkerof environmentaltobaccosmokeexposure.Epidemiol.Rev. 18, 188*204. Benowitz, N., Jacob, P., 1993. Nicotine and cotinine elimination pharmacokineticsin smokers and non-smokers.Clin. pharmac o l . T h e r . ,5 3 . Cains,T.,Cannata,S.,Poulos,R., Ferson,M., Stewart,B.,2004.Designated"no smoking" areasprovide from partial to no protection from environmentaltobaccosmoke.Tob. Control 13,17-22. CoilinsA , . , G e d i k ,C . , O l m e d i l l a 8 , . , S o u t h o nS, . ,B e l l i z z i ,M . , 1 9 9 8 . Oxidative DNA-damage measuredin human lymphocytes:large differencesbetween sexesand between countries,and correlations with heart diseasemortality rates.Federationof Soc. Exp. Biol. J. 12.1397-1400. Delorenze, G., Kharrazi, M., Kaufman, F., Eskenazi,B., Bernert, J.,2002. Exposureto environmentaltobaccosmokein pregnant women: the associationbetweenself-reportand serumcotinine. E n v i r o n .R e s .9 0 , 2 l - 3 2 . Gackowski,D., Speina,E., Zielinska,M., Kowalewski,J., Rozalski, R., Siomek,A., Paciorek,T., Tudek,B., Olinski, R., 2003.products of oxidative DNA-damage and repair as possiblebiomarkers of susceptibility to lung cancer. Cancer Res. 63, 4999_ 4902. Gantt, R., Parshad,R., Price, F., Sanford,K., 1986. Biochemical evidencefor deficient DNA repair leading to enhancedG2 chromatid radiosensitivityand susceptibility to cancer.Radiat. Res. t08,tt7-126. Glynn, L., Emmett,P.,Rogers,I.,2005. ALSPAC StudyTeamFood andnutrientintakesof a populationsampleof 7-year-oldchildren in the south-westof England in 199912000-what differencedoes gendermake?J. Hum. Nutr. Diet 18,7-19. Gries,J., Benowitz,N., Verotta,D., 1996.Chronopharmacokinetics of nicotine.Clin. Pharmacol.Ther. 60, 389-395. Heloma, A., Jaakkola,M., Kahkonen, 8., Reijula, K., 2001. The short term impact of nationalsmoke-freeworkplacelegislation on passivesmoking and tobaccouse. Am. J. public Health 91, t4t6-1418. Howard, D., Ota, R., Briggs, L., Hampton, M., pritsos,C., 1999. Environmentaltobacco smoke in the workplace inducesoxidative stressin employees,including increasedproductionof 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers P r e v . 7 2 l. 4 l - 1 4 6 . Iribarren,C., Darbinian,J., Klatsky, A., Friedman,G., 2004. Cohort study of exposureto environmentaltobaccosmoke and risk of first ischemicstroke and transientischemic attack.Neuroepidemiology23,3844. lto, H., Matsuo,K., Hamajima,N., Mitsudomi,T., Sugiura,T., Saito, T., Yasue,T., Lee, K.-M., Kang, D., Yoo, K.-y., Sato,S., Ueda, A.C. Collier et al. / TbxicologyLetters 155(2005) l0-19 R., Tajima, K., 2004. Gene-environmentinteractions between the smoking habit and polymorphisms in the DNA repair genes, APE I AspI 4BGlu andXRCC I Arg399Gln,inJapaneselung canc e r r i s k .C a r c i n o g e n e s2i s5 , 1 3 9 5 - 1 4 0 1 . Kobayashi,H., Sugiyama,C., Morikawa,Y., Hayashi,M., Sofuni,T., 1995.A comparisonbetweenmanual and microscopicanalysis and computerizedimage analysisin single cell electrophoresis a s s a yM . M S C o m m u n .3 , 1 0 3 - l 1 5 . Kurtz, M., Kurtz, J., Contreras,D., Booth, C.,2003. Knowledgeand attitudesof economicallydisadvantagedwomen regardingexposure to environmentaltobacco smoke: a Michigan, USA study. E u r .J . P u b l i cH e a l t h1 3 . 1 ' 1 1 - 1 7 6 . Kyerematen,G., Morgan, M., Chattopadhyay,8., de Bethizy, J., Vesell,E., 1990.Dispositionof nicotine and eight metabolites in smokersand non-smokers:identificationin smokersof two metabolitesthat are longerlived than cotinine.Clin. Pharmacol. T h e r . 4 8 ,6 4 1 6 5 1 . Levi, F., Lucchini,F., Negri, 8., Vecchia,C.L.,2004. Trendsin mortaliry fiom major cancersin the EuropeanUnion, including accedingcountries,in 2004. Cancer101,2843-2850. Loft, S., Vistisen, K., Ewertz, M., j-onneland,A., Overvad, K., Poulsen, H., 1992. Oxidative DNA-damage estimated by 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosineexcretion in humans: influence of smoking, gender and body mass index. Carcinogenesis13, 2241-224',7. Manton, K., 2000. Gender-differences in the cross-sectionaland cohort age dependenceof cause-specificmortality: the United States,1962-1995.J. Gend. Specif.Med. 3, 4i-54. MolecularProbes,2004. Nucleic Acid Detectionand euantitation in E,lectrophoretic Gelsand Capillaries.MolecularProbesIncorporated,FosterCity, CA. Park,J.,Chen,L., Tockman,M., Elahi,A.,Lazarus,P.,2004.Thehuman 8-oxoguanineDNA N-glycosylaseI (hOGGl) DNA repair enzymeand its associationwith lung cancer risk. pharmacogen e t i c s1 4 ,1 0 3 1 0 9 . l9 Reynolds,P.,Goldberg,D., Hurley, S., 2004. Prevalenceand pattems of environmental tobacco smoke exposuresamong California teachers;California TeachersStudy SteeringCommittee.Am. J. HealthPromot. 18, 358-365. R o j a s , 8 . , L o p e z , M . , V a l v e r d e ,M . , 1 9 9 9 . S i n g l e c e l l g e l e l e c trophoresis.Methodology and applications.J. Chromatogr.B t-2,225-254. Soliman,S., Pollack,H., Warner,K.,2004. Decreasein the prevaIenceof environmentaltobaccosmoke exposurein the homeduring the 1990sin familieswith children.Am. J. public Health94, 3t4-320. Speit,G., Witton-Davies,T., Heepchantree, W.,Trenz,K., Hoffmann, H., 2003. Investigations on the effectof cigarettesmokingin the Comet assay.Mut. Res.542, 3342. Sram, R., Rossner,P., Peltonen,K., Podrazilova,K., Mrackova, G., Demopoulos,N., Stephanou,G., Vlachodimitropoulos,D., Darroudi,F., Tates,A., 1998.Chromosomalaberrations,sisterchromatid exchanges,cells with high frequencyof SCE, micronuclei and Comet assayparametersin 1,3-butadiene-exposed workers.Mut. Res. 419,145-154. Tricker, A., 2003. Nicotine metabolism,human drug metabolism polymorphisms and smoking behaviour. Toxicology 183, l5l-153. Tuimala, J., Szekely,G., Gundy, S., Hirvonen, A., Norppa, H., 2002. Genetic polymolphisms of DNA repair and xenobioticmetabolizingenzymes:role in mutagensensitivity.Carcinogene s i s2 3 , 1 0 0 3 - 1 0 0 8 . Wingo,P.,Cardinez,C., Landis,S.,Greenlee,R., Ries,L., Anderson, R., Thun, M., 2003. Long-termtrendsin cancermortality in the United States,1930-1998.Cancer9i, 3133-32i5. Yang,M., Kunugita,N., Kitagawa,K., Kang, S.,Coles,B., Kadlubar, F., Katoh, T., Matsuno,K., Kawamoto,T., 2001. Individualdifferencesin urinary cotinine levels in Japanesesmokers:relation to geneticpolymorphism of drug-metabolizingenzymes.Cancer Epidemiol.BiomarkersPrev. 10, 589-593.

© Copyright 2026