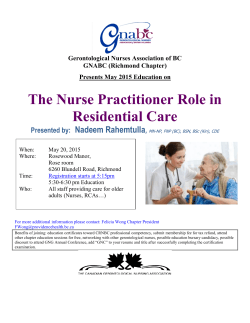

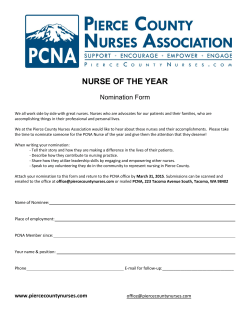

fulltext