Judicial Involvement in the Plea Bargaining Process . The American perspective

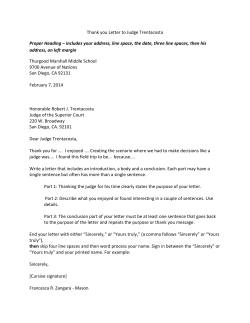

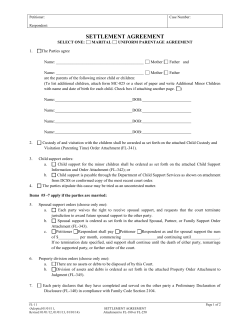

Judicial Involvement in the Plea Bargaining Process The American perspective Scope of judicial involvement during the process. Federal Judges are not allowed to participate in the plea negotiation process- Section 11 Federal Rule of Criminal Prosecution. United States v. Bruce1 provides case authority. State Judges may follow Section 11 as a guideline but it is non-binding. However, they should as far as possible do so to avoid raising a constitutional issue. If: 1. the judge’s involvement does not coerce or cause the defendant to misunderstand the nature of the charges/consequences against him; and 2. the judge agrees to remove himself from further participation in judicial duties on the matter; and 3. his involvement is “moderate” in the sense that he does not opine on the merits of the case or comment on the possibility of conviction, the agreement may stand given that the judge’s involvement has no constitutional implications. State of Kansas v John McCray)2. Refining these exceptions further, State of Wisconsin v Corey D. Williams3 lays down the precedent that judicial participation in the bargaining process that precedes a defendant’s plea raises a conclusive presumption that the plea was involuntary. 1 976 F.2d 552, 557-58 (9th Cir. 1992). 2 Decided on 9 April 2004 3 2003 WI App 116 1 Arguments for judicial non-intervention 1. Such involvement makes it difficult for a judge to objectively assess the voluntariness of the plea entered by the defendant; 2. judicial participation in plea discussions resulting in failure inherently risks the loss of a judge’s impartiality during trial, because he has become aware of the defendant’s possible interest in pleading guilty, and because he may have viewed unfavorably the defendant’s rejection of the proposed agreement; 3. involvement in plea negotiations diminishes the judge’s objectivity in post-trial matters such as sentencing and motions for a judgment of acquittal Plea Agreements – judicial involvement post-bargaining Plea bargains in the States, if an agreement is reached, must be recorded in a Plea Agreement document which fully sets out the terms of the agreement. The Defendant must state that such agreement is reached without coercion and that by agreeing to the terms he waives certain constitutional rights otherwise available to him. The agreed factual basis of what would have been proved should a trial have taken place are also recorded. This is to assist the judge in sentencing. (It is unclear how much of it is left out as part of concessions made during negotiations if at all). The agreement also contains a clause which stipulates that the terms of the agreement do not necessarily bind the courts who merely have to take it under advisement. All parties to the agreement sign it and it must be ratified by a judge to have legal effect. 2 The Australian perspective Scope of judicial involvement during the process Proceedings in Australia must be conducted publicly and in open court4. No exception, statutory or otherwise, applies for in camera bargaining. Judicial involvement post-bargaining From the sources considered, it seems that plea bargains are never expressly referenced in open court; the judge merely officiates the result without knowing the process behind it or considering the substantive merits of it. DPP Policy Guidelines outline the circumstances in which a plea bargain may be tendered and on what terms. So long as the agreement reached is in all the circumstances reasonable, the judge will as a matter of course accept the plea and proceed to sentencing based upon the facts agreed to be disclosed. These agreed facts must not be such as to create an artificial basis for sentencing which does not reflect upon the criminality of the offence. 4 McPherson v McPherson [1936] AC 177, 200 3 Towards a Formal Structure of Plea Bargaining If any formal structure of plea bargaining were to be proposed, we must consider the manner in which we can implement the system and maximize the benefits flowing from it while minimizing as much as possible the inherent drawbacks. Pros Cons • Faster disposal of cases resulting in a reduced backlog. • Risk of alienating victims (though this is not a pre-existing consideration in Malaysia) • Lesser time spent in remand for the accused. • Bargaining parties may be perceived to be exercising quasi-judicial functions. • Higher conviction rate with less cases falling through for want of evidence. • Absurdly lenient punishment relative to the original offence charged may result. • Spare witnesses from the stresses endemic to trials. Reduce the risk of unsuccessful trials for want of testimony from witnesses withdrawing/not co-operating. • Risk that justice is perceived to be merely an economic consideration thus bringing the profession to disrepute and undermining confidence in the system. • Greatly reduced strain on logistics (time, money, human capital) = happier and hence more efficient employees in the administration of justice. • Lack of legal representation in general means that there is a risk of, or apparent risk of, ‘coercion’ especially amongst the poorest and the least intellectually equipped members of society. • An invaluable bargaining tool with which to catch Ikan Tuna using Ikan Bilis as bait. • Process not governed by strict rules of evidence; the bargaining chips may be tainted hence unfairly coercive. 4 From the classic arguments for and against plea bargaining, it can be argued that a formalized (hence regulated and transparent system), if properly drafted and implemented, can meaningfully reduce the inherent drawbacks given that some of those are matters relating to perception rather than substantive justice. Issues relating to fairness too have been proven time and again to be best served by rendering the relevant processes as transparent as possible, which (should) flow naturally with formal regulation. Factors which affect the possibility and outcome of a plea bargain Enumerated below are measures that can influence the likelihood of an agreement on plea being reached as well as encourage the parties to consider plea-bargaining as a satisfactory alternative to trial. Disclosure – Malaysian position Before any meaningful negotiations as to plea could be held, a basis for tabling suggestions and concessions must first be established. In this respect, Section 51A of the CPC requires that the prosecution disclose, in essence, the entirety of the investigation papers generated. Caselaw bars the disclosure of 112 statements however, and given that this makes up the bulk of prosecution evidence against the accused, it is likely that any ‘disclosure’ of information contained therein would be through oral representations made by the DPP during negotiations. Already it has been stated that the strict rules of evidence do not apply when bargaining. Added to the imperfect disclosure regime in our current system and the lack of legal representation for many offenders, it wouldn’t require any imagination to see the potential abuses which may accrue over the bargaining table. Disclosure under the Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act 1996 Crown Prosecutors are under a duty to disclose (meaning to provide copies of, or access to) materials that may undermine the prosecutions case or assist the case for the accused5. The CPS is further required to list any unused material on a separate schedule for the defence to vet. The latter may request inspection of these materials. Sensitive materials are to be listed on a separate schedule for the prosecutor’s consideration. Should the prosecutor contend that the material should be withheld from 5 Section 3 CPIA 1996 5 inspection by the accused, the matter of whether to grant inspection is the discretion of the judge (contrast with Malaysian position) and shall be dealt with pre-trial in open court. Traditionally this privilege is exercised to protect the identity of informants. Following that, the defence must issue a Defence Statement to the prosecution within 14 days of the initial disclosure setting out, as is reasonably practicable at this stage of the proceedings: • Particular defences to be relied on at trial; • Facts which the accused takes issue with the prosecution and why; • Points of law and authorities relied on; and • Any and all witnesses the Defence proposes to call in support of their case. Caselaw has been consistent in insisting that the defence provide as full an account of their case as possible to ensure that issues are quickly brought out into the open. Even after initial disclosure has been complied with, both defence and prosecution are under a continuing duty to review the question of disclosure as the case progresses. The regime of disclosure created by the CPIA 96 therefore seems to be more conducive to reaching an agreement over plea as both parties are afforded a complete view of the transaction. The preparation of defence statements at an early stage in the proceedings further focuses the issues in contention. Charges and sentences Whether the proffered alternative charge (and consequently the associated sentences) would appeal to the offender depends firstly upon what the original charge is. In general terms, the following factors forseeably affect the choice of plea: • Whether the alternative sentence afforded by the amended charge is subject to a minimum period of detention; • Discretionary leeway given to the sentencing court for passing sentence; • How much of a discount the accused is entitled to when pleading guilty; and • When the death penalty is involved. Bargaining for lower charges is one thing, but that wouldn’t amount to much if there is uncertainty in sentencing practice. This concern is more pronounced if the upper sentencing band of the bargained charge comes close or even overlaps with the lower 6 sentencing band of the original offence. Thus, any formal structure of plea-bargaining should be accompanied with parallel efforts on standardizing the latter. Sentencing Trends and Alternative Sentencing Options Excepting mandatory sentences, the judge’s choice of sentence is carte blanche. Considering that some alternative sentences recently enacted move away from punitive and custodial measures to rehabilitative ones, it would be seen as desirable from the point of view of the accused to plead guilty to a charge which avails him to non-custodial sentences. From this point on, the prosecution and defence can agree certain sentence proposals to be put forward during the plea in mitigation stage. Whether the judge would be minded to give effect to these proposals is another matter, but as has been demonstrated in Australia and America, sentencing judges more often than not would agree to a proposal provided that it is not manifestly unjust. Lessons learned from cross-jurisdictional comparisons 1. Judicial involvement during negotiations has been seen to increase the coercive effect of bargains, especially in the United States where this has formed the basis of successful appeals. 2. In plea agreements already reached, making the process open and referring to it in express terms ensures that the judge knows what he is dealing with and thus may make enquiries as required before coming to a decision. 3. Tighter sentencing guidelines help along the bargaining process by promoting greater certainty in the eventual outcome and at the same time lessen the chances of the case going on appeal for ‘misrepresentation’. 4. DPP’s and Defence Counsel sometimes agree to hide facts which then creates an artificial base for sentencing. Transparency and regulation would thus hold the parties to make ethical and sound agreements. 5. Plea bargains done in the back-room do not at all help with public confidence much less the DPP’s relationship with the police. 6. In foreign jurisdictions, the importance of disclosure vis a vis plea bargaining is not at all talked about; this is because they already enjoy full disclosure. It therefore follows that implementing a regime of full and frank disclosure as in the 7 UK CPIA Code of Practice is a necessary stepping stone before we can speak meaningfully of bargaining. By: Farhan Read 8

© Copyright 2026