Document 45558

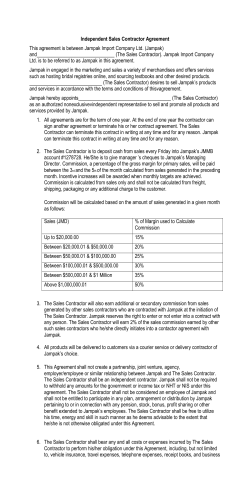

Platform supply vessels battle the blazing remnants of the offshore oil rig Deepwater Horizon (Image credit: US Coast Guard) Chidi Egbochue Herbert Smith Freehills, London Reviewing ‘knock for knock’ indemnities following the Macondo Well blowout In the oil and gas world, contractual ‘knock for knock’ indemnities (otherwise known as ‘mutual hold harmless’ or ‘bury your own dead’ indemnities) seem to be a way of life. However, recent oil rig disasters have brought them sharply into focus. The Piper Alpha, Montara and Macondo oil rig disasters Piper Alpha It is just over 24 years since the Piper Alpha disaster shocked the world. On 6 July 1988, the Piper Alpha oil platform was operating in the CONSTRUCTION LAW INTERNATIONAL Volume 7 Issue 4 January 2013 North Sea, 120 miles off the north east coast of Scotland with 229 people on board when an explosion occurred. The explosion and the resulting fires claimed the lives of 167 people, with all the survivors suffering injuries. Most of the dead and the survivors were employed by contractors, against whom the operator 7 FEATURE ARTICLE brought claims for indemnity in respect of payments it made to settle the resulting death and personal injury claims. The disaster led to an insurance loss of US$1.4bn.1 Piper Alpha remains the world’s most catastrophic oil rig disaster in terms of fatalities. Montara In the last few years, there have been two oil pollution environmental catastrophes. On 21 August 2009, an uncontrolled release of oil and gas (ie, a blowout) from the Montara Wellhead platform operating 250km off the north west coast of Australia resulted in oil and gas spilling into the Timor Sea for almost 11 weeks at a rate of 400 barrels (64 tonnes) a day (but the initial discharge may have been as much as 1,000 to 1,500 barrels a day). The area affected by the spill was around 90,000 square kilometres.2 The operator was fined AU$510,0003 and is also facing a US$2.4bn compensation claim from the Indonesian government.4 Montara was Australia’s worst petroleum industry disaster. ‘A central cause of the Macondo Well blowout was found to be the failure of a cement barrier in the production casing string’ Macondo Just eight months after the Montara disaster, the ‘worst environmental disaster America has ever faced’5 occurred. On 20 April 2010, a blowout from the Macondo exploratory well in the northern Gulf of Mexico, off the coast of Louisiana, triggered a number of explosions and a huge fire which raged unabated for two days. The well was being drilled by the Deepwater Horizon drilling vessel, which was abandoned shortly after the fire started. Of the 126 people on board the vessel, 11 were killed and 17 others were injured. The vessel sank 36 hours after the fire started. The riser and the drill pipe inside it bent and broke off at the top of the subsea blowout preventer, spewing gas and oil into the sea.6 Over the next 87 days, almost five million barrels of oil were discharged from the well into the Gulf of Mexico. The US government responded by imposing a six month moratorium on all 8 deepwater offshore drilling on the Outer Continental Shelf, and introducing stringent new regulations.7 A central cause of the Macondo Well blowout was found to be the failure of a cement barrier in the production casing string. This allowed hydrocarbons to flow up the wellbore through the riser and onto the rig.8 The Deepwater Horizon was owned by Transocean and leased to BP, as the operator on behalf of itself and its joint venture partners, Anadarko and Mitsui (through its subsidiary MOEX); their respective shares in the Macondo Prospect were 65 per cent, 25 per cent and 10 per cent. Halliburton was BP’s cement contractor (through its subsidiary Sperry Sun) and the Deepwater Horizon’s blowout preventer was designed by Cameron.9 In the two weeks following the explosions, 70 lawsuits were filed by commercial fishermen, property owners, area businesses, municipalities, seafood processors and recreational users against BP, Transocean, Halliburton and Cameron.10 Following an extensive investigation, US regulators issued environmental and safety violation notices to BP, Transocean and Haliburton.11 BP launched multi-billion dollar suits against Transocean, Halliburton and Cameron.12 Recently, BP agreed a US$7.8bn deal to settle 100,000 claims by individuals and businesses, covering economic, property and medical claims,13 and it has been reported that the US Department of Justice is nearing settlements with BP and Transocean that could involve civil fines ranging from US$5bn to US$21bn, and criminal fines of up to US$28bn.14 A common feature of the litigation that ensued from the Piper Alpha and the Macondo disasters was the reliance placed by the operator (in the case of Piper Alpha) and by the vessel owner and contractors (in the case of Macondo) on knock for knock indemnities (‘KK Indemnities’) to limit their financial exposure to third parties’ claims for negligence and breach of statutory duty, and to statutory fines and penalties. What are knock for knock indemnities? The basic form of a knock for knock indemnity In the oil and gas sector, a KK Indemnity in its most basic form provides that party A (eg, an CONSTRUCTION LAW INTERNATIONAL Volume 7 Issue 4 January 2013 operator) indemnifies party B (eg, a drilling contractor) against claims in respect of any: • death of, or personal injury to, party A’s employees; • loss of, or damage to, party A’s property (but, with regard to KK indemnities given under construction contracts, excluding loss of, or damage to, the works being constructed); and • pollution emanating from party A’s property. The above are all notwithstanding that party B’s negligence or breach (whether of contract or of statutory duty) may have caused or contributed to the death, personal injury, loss, damage or pollution in question. In return, party B provides a reciprocal indemnity in favour of party A. ‘KK Indemnities should be expressly carved out from any cap on the indemnitor’s aggregate liability and from any exclusion of its liability for “consequential loss”’ Extension of benefit of knock for knock indemnity to party’s group A knock for knock indemnity will usually also cover a party’s ‘group’, which may include a party’s affiliates, contractors, subcontractors and its and their respective officers, employees and agents. In many jurisdictions, the members of the group may have express rights to enforce such indemnities despite not being parties to the contract.15 Recovery of legal costs under knock for knock indemnities It is commonplace for KK Indemnities expressly to provide for recover y of the indemnitee’s reasonable legal costs or attorney fees. However, in Case 2:10-md-02179CJB-SS Document 5446 Filed 01/26/12 (BP/ Transocean), which was a case arising out of the Macondo disaster, a Louisiana District Court construed such a provision as not covering Transocean’s legal costs of establishing a right to indemnification. Aggregate liability cap and consequential loss exclusion carve-outs KK Indemnities should be expressly carved out from any cap on the indemnitor’s aggregate liability and from any exclusion of its liability for CONSTRUCTION LAW INTERNATIONAL Volume 7 Issue 4 January 2013 ‘consequential loss’ (as defined in the relevant contract) to forestall arguments as to whether or not the indemnities were intended to provide full coverage for the claims in question. This is exemplified by the consequential loss and aggregate liability cap arguments which were raised, albeit unsuccessfully, in Caledonia North Sea Ltd v London Bridge Engineering Ltd [2002] UKHL 4, known as the London Bridge case (which was a House of Lords’ Scottish case relating to the Piper Alpha disaster), and Westerngeco Ltd v ATP Oil & Gas (UK) Ltd [2006] EWHC 1164 (COM), respectively. The interplay between knock for knock indemnities and insurance Any obligation of the indemnitor to insure against the risk under a KK Indemnity is likely to be construed as being independent from the indemnity itself, although this is often expressly stated in contracts. Insurance policies may not cover gross negligence or wilful misconduct, or civil or criminal fines or penalties. Where the indemnitee, notwithstanding that it has the benefit of a KK Indemnity, effects insurance to cover the risk, the indemnitor will still have primary liability and the insurer will have only secondar y liability and will be subrogated to the rights of the indemnitee (this is the position under English law – see the London Bridge case – but not necessarily other jurisdictions). The justification for knock for knock indemnities KK Indemnities are a particular feature of the oil and gas industry. The alternatives are ‘guilty party pays’ (ie, fault based) indemnities or staying silent in the contract (in which case applicable law – that is, statutor y duties and, under English law, the law of negligence – will determine liability). However, these alternatives may be impractical in view of the complexity and delay (both to the resolution of claims and to production; for example, rig downtime due to in situ investigations) involved in establishing cause and attributing fault where hazardous operations and numerous interfacing parties are involved and the substantial financial risks that the supply chain would be exposed to. Furthermore, contractors and subcontractors would have to insure against those risks, which would give rise to multiple overlapping layers of 9 FEATURE ARTICLE insurance and high insurance premiums that would be passed on ultimately to the operator. Under a KK Indemnity regime, each party is only required to insure against the death of, or personal injury to, its own employees (which insurance is mandatory for employers in many jurisdictions in any case) and loss of or damage to, and pollution emanating from, its own property. Indemnities in respect of liability to third parties With respect to third parties (excluding third parties that are defined as being part of either party’s group), it is common for oil and gas service contracts to provide for ‘guilty party pays’ reciprocal indemnities. This means that party A indemnifies party B and party B’s group against claims in respect of any: • death of, or personal injury to, third parties; and • loss of or damage to the property of third parties (excluding pollution damage, which will be addressed in the KK Indemnities). Again, the above are to the extent caused by the negligence, breach of statutory duty or breach of contract of party A or its group. Conversely, Party B provides a reciprocal indemnity in favour of party A and party A’s group. Alternatively, contractors may give an indemnity in respect of third parties’ claims arising out of the contractor’s operations except to the extent caused by any negligence, breach of statutory duty or breach of contract by the operator or any member of its group. This puts the onus on the contractor to prove such negligence or breach and therefore fills a gap where it is difficult to prove which party (if any) caused the death, personal injury, loss or damage in question. Are knock for knock indemnities enforceable? There are only a few instances where KK Indemnities have been considered by the courts. In the London Bridge case, Lord Bingham referred to a KK Indemnity that covered employees as a ‘market practice [that] has developed to take account of the peculiar features of offshore operations’. It was held that the KK Indemnity, properly construed, entitled the operator to indemnity from the contractors even where they were not liable at common law, or liable for breach of statutory duty, in respect of the fatalities and injuries. 10 However, there was no discussion in the London Bridge case of the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 (‘UCTA’) which applies to UK jurisdictions and which provides that a party cannot exclude or restrict its liability ‘Certain jurisdictions may have public policy objections to certain aspects of KK Indemnities’ for death or personal injury caused by negligence and which can only exclude or restrict its liability for any other loss or damage if the relevant contract term or notice is reasonable. It is noted that UCTA does not apply to contracts where the governing law of the contract would not be English law (or another UK jurisdiction) but for the choice of law made by the parties. However, even where contracts come within the scope of UCTA, it can be argued that KK Indemnities do not operate as exclusions of, or limitations on, liability for death and personal injury, rather they ‘simply shift the source of compensation without restricting the injured party’s right to cover’ (a quotation by Judge Barbier in BP/Transocean), in the same way as this can be transferred to an insurer. Further, with regard to liability for property loss and damage, KK Indemnities can be considered to be reasonable due to the impracticability of the alternatives, as discussed above, and the fact that they are negotiated between parties who have the benefit of legal advice and who do not have disproportionately unequal bargaining power. Also, it appears from the Macondo cases that KK Indemnities will generally be enforced by US courts. This was affirmed by American maritime lawyer LeRoy Lambert in an article in Standard Bulletin following the Macondo disaster and other articles in the same publication asserted that KK Indemnities would be effective under Brazilian law and Mexican law.16 KK Indemnities are also commonly used in oil and gas contracts for the North West Shelf of Western Australia (WA) and there is no reason to believe that they would not be enforced by WA courts. South/South East Asia has also widely adopted KK indemnities17 and again they should be enforceable in the relevant jurisdictions. However, certain jurisdictions may have public policy objections to certain aspects CONSTRUCTION LAW INTERNATIONAL Volume 7 Issue 4 January 2013 Standard form Death/personal injury & loss/ damage KK Indemnities Pollution KK Indemnity Extension to party’s group Consequential loss LOGIC Construction Contract Ed, 2 Oct 2003 Company also indemnifies Contractor Group in respect of loss/damage to permanent third party oil and gas production facilities, and consequential losses (as defined) therefrom. Contractor indemnifies Company Group against claims in respect of pollution occurring on or emanating from Contractor Group’s premises, property or equipment. Company Group does not include Company’s other contractors. Each party indemnifies the other against claims for Consequential Loss (as defined) from its party Group. Company Group includes Company’s other contractors. Neither party is responsible to the other for Consequential Damages (as defined). Expressly stated that all of these indemnities and the pollution indemnities apply irrespective of cause and notwithstanding negligence or breach of duty of indemnified party. AIPN Model Well Services Contract 2002 Operator also indemnifies Contractor in respect of Contractor Group equipment lost or damaged Down Hole. Indemnities do not apply to death, personal injury, loss or damage caused by gross negligence or wilful misconduct of the other party. BIMCO Time Charter Party for Offshore Service Vessels 2005 Expressly stated that indemnities apply even if caused by the act, neglect or default of other party Group or un-seaworthiness of any vessel. Company indemnifies Contractor Group against claims in respect of pollution emanating from the reservoir or Company Group’s property. Operator indemnifies Contractor against claims arising from a Work Site fire or explosion or blowout, cratering or uncontrolled well condition, regardless of cause. Alternative two also adds an indemnity in respect of each Party’s Group Consequential Damages claims. Another Alternative carves out gross negligence. Alternative two carves out gross negligence (including wilful misconduct), and Alternative three also carves out Negligence up to a stated monetary cap. Owners indemnify Charterers against claims for pollution damage arising from acts or omissions of Owners or their personnel which cause discharge, spills or leaks from vessel other than emanating from cargo thereon. Charterer Group includes Charterer’s contractors. Each party indemnifies the other against claims for consequential damages (as defined) from its party Group. Charterers indemnify Owners against claims in respect of all other pollution damage, even if caused by the act, neglect or default of Owners Group or un-seaworthiness of any vessel. of KK Indemnities (see below) or specific legislation that imposes limitations on KK Indemnities (for example, Texas, Louisiana, New Mexico and Wyoming have in place ‘Oilfield Anti-Indemnity Acts’,18 and Part 1F of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (a Western Australian statute) undermines the ‘loss lies where it falls’ principle of KK Indemnities). CONSTRUCTION LAW INTERNATIONAL Volume 7 Issue 4 January 2013 A survey of knock for knock indemnity regimes Knock for knock indemnities in standard forms of contract KK Indemnities are incorporated in many standard forms of contract that are widely used in the oil and gas and marine sectors worldwide. The following table highlights particular KK Indemnity provisions in certain LOGIC, AIPN and BIMCO standard forms. 11 FEATURE ARTICLE As can be seen from the table above, KK Indemnities may: • include a carve-out of gross negligence or wilful misconduct; • exclude the operator’s other contractors from the definition of the operator group; • include a modified KK Indemnity whereby a contractor carries the risk of pollution damage (or loss of, or damage to, the operator’s property) caused by its group’s negligence or breach up to a stated cap (which may be intended to cover the operator’s deductible under its insurances); and • include indemnities against each party group’s claims for ‘consequential loss’ (as defined in the relevant standard form). Indemnities against ‘consequential loss’ claims by the other party’s group may be regarded as ‘belts and braces’ drafting,19 as such claims are only likely to arise out of the negligence of a contractor that results in physical damage and economic loss consequential on that damage (at least this is the position under English law – see the judgment of Lord Denning MR in Spartan Steel and Alloys Ltd v Martin & Co (Contractors) Ltd, 1972 ABC L R 06/22). Accordingly, such loss should fall within the scope of a properly drafted KK Indemnity. Separate knock for knock indemnity schemes for operator’s other contractors Where the operator’s other contractors are not included in its group they will fall to be treated as ordinary third parties (see above). However, the contract may make specific provision for such contractors. For example, in the Western Australian oil and gas sector, contractors may exchange reciprocal indemnities in their respective contracts to cover their respective groups’ claims for death and personal injury, property loss and damage and ‘consequential loss’ (as defined in the relevant contracts). The contracts will usually provide that a contractor group can only enforce such indemnity if the contractor has provided a reciprocal and enforceable indemnity in favour of the defaulting contractor and its contractor group. Ten years ago, LOGIC introduced a voluntary ‘IMHH’ (industry mutual hold harmless) deed scheme which was updated this year. The scheme applies to contractors 12 working on the UK continental shelf, and is similar to the contractor reciprocal indemnity scheme mentioned above. Excluding liability in knock for knock indemnities – how far can you go? In the few cases where KK Indemnities have been considered by the courts, certain principles have emerged that apply to the jurisdictions concerned. Express statement of applicability to negligence required It is clear that English and US courts will not construe a KK Indemnity as applying where the indemnified party’s negligence has caused the death, personal injury, loss, damage or pollution in question (even if the clause states that it applies whatsoever the cause) unless the clause expressly states that it applies notwithstanding such negligence.20 Public policy In BP/Transocean, the Louisiana District Court held that public policy does not prohibit a party benefiting from an indemnity against claims arising from its own gross negligence (which some legal systems, but not English law, recognise as a distinct concept from negligence). However, the Court also held that where the objectives of civil penalties are to punish and deter (rather than to compensate), then, similar to punitive damages, public policy prohibits contractual indemnification of such penalties. It is also clear that public policy in many jurisdictions will not allow indemnities to extend to criminal fines and penalties or indemnitees who have committed fraud. In a separate Macondo case, Case 2:10-md02179–CJB-SS Document 5493 Filed 01/31/12, in response to BP’s allegation that Halliburton had made fraudulent statements and fraudulently concealed material information, the Louisiana District Court agreed ‘that fraud could void an indemnity clause on public policy grounds’. See also the English cases of Askey v Golden Wine Company Limited and Others [1948] 2 All ER 35, and HIH Casualty and General Insurance Ltd & Ors v Chase Manhattan Bank & Ors [2003] UKHL 6 regarding criminal fines and penalties, and fraud respectively. Can an indemnitee’s breach of contract invalidate a knock for knock indemnity? One area of uncertainty is whether a breach of contract can invalidate an indemnity. In the English case of Smedvig Ltd v Elf Exploration UK Plc (The Super Scorpio II) [1998] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 659, a drilling contractor damaged an ROV which was a Company Item covered by a KK Indemnity in favour of the contractor. However, the operator argued that the damage was caused by the contractor breaching an express contractual obligation to take all necessary care of Company Items and that such breach invalidated the indemnity. The Court decided that this obligation was not irreconcilable with the KK Indemnity, which it upheld. The English case of A Turtle Offshore SA & Anor v Superior Trading Inc [2008] EWHC 3034 (Admlty) concerned a tug that was hired to tow an offshore rig from Brazil to Cape Town, but ran out of fuel. The rig was scuttled and its owners brought a claim for damages against the tug owners for the loss of the rig. The Court held that whilst the tug owners were in breach of their obligations under the tow contract (TOWCON) to ensure that the tow carried sufficient fuel and to use best endeavours to perform the towage, the KK Indemnity in favour of the tug owner covered the type of loss that was the subject of the rig owners’ claim. However, the Court also stated obiter dicta that the KK Indemnity should be ‘construed in the context of the TOWCON as a whole and to give effect to the main purpose of the CONSTRUCTION LAW INTERNATIONAL Volume 7 Issue 4 January 2013 13 FEATURE ARTICLE TOWCON’, and should be construed as ‘applying so long as the tug owners are actually performing their obligations under the TOWCON, albeit not to the required standard’ to ensure that the tug owners’ obligations are ‘more than a mere declaration of intent’. In BP/Transocean, BP argued that Transocean had breached the contract and/ or acted in a way such as to materially increase BP’s risk as indemnitor, thereby voiding the indemnity. The Louisiana District Court accepted that it was ‘possible that a breach of ‘The supply chain must be incentivised to ensure that risks are effectively identified and managed to avoid environmental damage’ a fundamental, core obligation of the contract could invalidate this indemnity clause’ but was not prepared to decide the issue in a summary judgment application. Conclusion KK Indemnities seem to be an integral part of the oil and gas industry worldwide (although the courts limit their scope – primarily on public policy grounds). It may be queried whether, given BP’s huge pollution liabilities as a result of the Macondo disaster, operators should tr y to apportion more pollution risk to the supply chain. Contractors may counter that the oil companies (rather than the contractors) have the financial resources to carry and insure pollution risk and they are therefore best-placed to manage this risk (since they are in overall control operationally) and should shoulder this risk as they stand to make substantial profits from the exploitation of oil and gas fields. However, the supply chain must be incentivised to ensure that risks are effectively identified and managed to avoid environmental damage. It is arguable whether the prospect of criminal fines and penalties (these being unlikely to be caught by KK Indemnities), which may arise only in the severest cases, and possible reputational damage provide sufficient motivation. Whilst 14 KK Indemnities are likely to remain market practice for the foreseeable future, in relation to pollution risk operators may increasingly insist on contractors bearing a proportion of this risk where they are negligent and on a gross negligence carveout from KK Indemnities. Notes 1 See, www.lloyds.com/news-and-insight/news-andfeatures/geopolitical/geopolitical-2008/twenty_ years_on_piper_alphas_legacy_23072008. 2 Report of the Montara Commission of Inquir y, June 2010. 3 ‘Thai company fined $510,000 over Montara’, The Australian (newspaper), 31 August 2012. 4 ‘It’s Claim and Counterclaim in Battle Over Timor Oil Spill’, Jakarta Globe, 30 August 2010. 5 Remarks by the President [President Obama] to the Nation on BP Oil Spill, 15 June 2010; see: www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarkspresident-nation-bp-oil-spill. 6 Final Report on the Investigation of the Macondo Well Blowout, Deepwater Horizon Study Group, 1 March 2011. 7 US Department of the Interior: Secretary Salazar’s Statement Regarding the Moratorium on Deepwater Drilling, ‘Interior Issues Directive to Guide Safe, Six-Month Moratorium on Deepwater Drilling’, 30 May 2010. 8 Report regarding the causes of the April 20, 2010 Macondo Well Blowout, The [US] Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement, 14 September 2011. 9 Ibid. 10 ‘Tide of oil spill lawsuits begins to rise’, Chicago Tribune, 18 May 2010. 11‘BP, Halliburton, Transocean Get U.S. Violation Notices’, Bloomberg, 13 October 2011. 12 ‘BP sues Halliburton and Transocean for $80bn over Gulf of Mexico disaster’, The Telegraph, 21 April 2011. 13 ‘BP’s $7,8 billion Gulf spill pact wins initial court ok’, Reuters.co.uk, 3 May 2012. 14 ‘US Nears BP Settlements’, US Edition of the Wall Street Journal, 29 June 2012. 15 For example, see the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 which applies to English law contracts and the Western Australian Property Act 1969. 16 The Standard Bulletin (Offshore Special Edition): www.standard-club.com/docs/16180Standard_ OffshoreBulletin_10.11_AW_PF10.pdf. 17Toby Hewitt, ‘An Asian perspective on model oil and gas services contracts’, Herbert Smith, March 2009. 18‘Oilfield Anti-Indemnity Acts and Their Impact on Insurance Coverage’, Insurance Journal, 22 August 2005. 19 Guidance Notes – International Model Contracts – Well Services and Seismic Acquisition, AIPN, 2002. 20 See, for example, BP/Transocean and the English case of EE Caledonia Ltd Orbit Valve Co Europe [1993] 1 WLR. Chidi Egbochue is a senior associate at Herbert Smith Freehills in London. The author is qualified in English law only and this article does not constitute and is not a substitute for legal advice. CONSTRUCTION LAW INTERNATIONAL Volume 7 Issue 4 January 2013

© Copyright 2026