ECR 2013 ( C-1858) The Pancreas

God Loves Variety Even if We Don't

Poster No.:

C-1858

Congress:

ECR 2013

Type:

Educational Exhibit

Authors:

A. Arora, R. Bhutani, A. Mukund, A. Kapoor, P. Yashwant, S. T.

Laroia, V. Bhatia, S. K. Sarin; New Delhi/IN

Keywords:

Congenital, Normal variants, Education, Diagnostic procedure,

Ultrasound, MR, CT, Pancreas, Abdomen, Developmental

disease, Education and training

DOI:

10.1594/ecr2013/C-1858

Any information contained in this pdf file is automatically generated from digital material

submitted to EPOS by third parties in the form of scientific presentations. References

to any names, marks, products, or services of third parties or hypertext links to thirdparty sites or information are provided solely as a convenience to you and do not in

any way constitute or imply ECR's endorsement, sponsorship or recommendation of the

third party, information, product or service. ECR is not responsible for the content of

these pages and does not make any representations regarding the content or accuracy

of material in this file.

As per copyright regulations, any unauthorised use of the material or parts thereof as

well as commercial reproduction or multiple distribution by any traditional or electronically

based reproduction/publication method ist strictly prohibited.

You agree to defend, indemnify, and hold ECR harmless from and against any and all

claims, damages, costs, and expenses, including attorneys' fees, arising from or related

to your use of these pages.

Please note: Links to movies, ppt slideshows and any other multimedia files are not

available in the pdf version of presentations.

www.myESR.org

Page 1 of 85

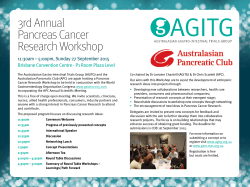

Learning objectives

It is often said that if God doesn't love variety,

why is there so much of it?

Recognition of variant morphology is one of the cornerstones of radiology, without a

sound knowledge of which a trainee struggles to become an astute radiologist.

This exhibit aims at:

1.

2.

3.

4.

Discussing a wide spectrum of normal variants, congenital anomalies and

pseudolesions of the pancreas and its ductal system.

The cross-sectional imaging appearances are illustrated with emphasis on

the most appropriate imaging technique for each condition.

The clinical implications and manifestations of these variants and anomalies

are highlighted.

Additionally, the embryologic basis is presented in a pictorial and simplified

manner, instead of the customary theoretical presentation.

Page 2 of 85

Images for this section:

Fig. 76: God Loves Variety Even if We Don't

© Ankur Arora

Page 3 of 85

Background

THE PANCREAS

Without history humans are demoted to lower animals....

Fig. 1: History of the pancreas.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Did you know....?

•

Pancreas was first discovered by Herophilus, a Greek anatomist and

surgeon (born in 336 BC).

Page 4 of 85

•

Four hundred years later, Ruphos, in the 1st or 2nd Century AD, an

anatomist-surgeon of Ephesus, gave the name 'pancreas'. Writing in Greek,

the word meant 'all flesh'.

•

Johann Georg Wirsüng, a German émigré, discovered the pancreatic duct in

Italy, in 1642, thereby initiating the study of the pancreas.

•

Pancreas as a secretory organ was investigated by Reignier de Graaf, a 22

year old student of Leiden, Netherlands in 1671.

•

D. Moyse, a student in Paris, was the first to describe the histology of the

pancreas in his thesis of 1852.

•

Paul Langerhans, a student at Berlin Institute of Pathology, described the

islets of the pancreas in his thesis of 1869, which were subsequently to be

known as the 'islets of Langerhans'

•

In 1889, Joseph F. von Mering and Oskar Minkowski of Strasbourg proved

that total pancreatectomy (in the dog) resulted in diabetes.

•

In 1921, at the University of Toronto, Frederick Grant Banting, a young

orthopedic surgeon, and Charles Herbert Best, a medical student,

discovered insulin. The digestive enzymes (amylase, lipase, trypsin, etc)

were discovered in the mid to late 19th century.

•

It was not until 1927, almost 35 years after the discovery of x-rays by

Wilhelm Conrad Röentgen on November 8, 1895 (Würzburg, Germany),

that an abdominal x-ray study first proved diagnostic of pancreatic disease

(pancreatic calculi). Radiologic imaging of the pancreas was to become an

essential step in the diagnosis of pancreatic disease....

•

In 1958, Frederick Sanger of England was awarded the Nobel Prize in

Chemistry for the determination of the molecular structure of insulin.

DEVELOPMENTAL ANALYSIS OF THE PANCREAS

Only the essentials...

Embryology of Pancreas:

•

The pancreas develops during the 4th to 5th weeks of gestation and arises

from dorsal and ventral buds, which originate from the endodermal lining of

the primordial foregut (duodenum).

Page 5 of 85

•

The ventral (V) and dorsal (D) buds develop on opposite sides of the

primordial foregut.

•

The ventral bud arises at the base of the hepatic diverticulum which forms

the liver, gallbladder and the bile ducts (Fig-2).

Fig. 2: The ventral (V) and dorsal (D) buds develop on opposite sides of the primordial

foregut. The ventral bud arises at the base of the hepatic diverticulum which forms the

liver (L), gallbladder and the bile ducts (B). The dorsal bud forms the dorsal portion of

the pancreas (DP) while the ventral bud forms the ventral pancreas (VP).

References: Ankur Arora

•

The dorsal bud forms the dorsal portion of the pancreas (DP) while the

ventral bud forms the ventral pancreas (VP).

•

During the further development, the developing ventral pancreas and bile

duct rotate clockwise (when viewed from the top) posterior to the duodenum

(Fig-3).

Page 6 of 85

Fig. 3: The developing ventral pancreas and bile duct rotate clockwise (when viewed

from the top) posterior to the duodenum, eventually being located just caudal and

posterior to the dorsal pancreas.

References: Ankur Arora

Page 7 of 85

Fig. 4: The ventral pancreatic duct and the CBD through a common entrance drain

into the duodenum at the major duodenal papilla. While the dorsal pancreatic duct

drains cranially at the minor papilla.

References: Ankur Arora

•

The ventral pancreatic duct and the CBD are, therefore, linked by their

embryologic origins (resulting in the adult configuration of their common

entrance into the duodenum at the major duodenal papilla) (Fig-4).

•

At about 7-weeks the two pancreatic components fuse.

•

The dorsal bud forms the pancreatic body, tail and anterior portion of the

head of the pancreas. The ventral bud becomes the uncinate process and

the remainder (posterior portion) of the pancreatic head (Fig-5).

Page 8 of 85

Fig. 5: The two pancreatic components fuse at about 7-weeks. The dorsal bud

forms the pancreatic body, tail and part of the head of the pancreas. The ventral bud

becomes the uncinate process and the remainder of the pancreatic head.

References: Ankur Arora

•

In the embryo, the dorsal duct remains the main drainage of the gland which

empties into the duodenum through the minor papilla (Fig-6).

Page 9 of 85

Fig. 6: The ducts get fused at the neck, however, initially inthe embryo the

predominant drainage remains through the dorsal duct, emptying at the minor papilla.

References: Ankur Arora

•

Whereas, in adults the distal part of the dorsal pancreatic duct and the entire

ventral pancreatic duct form the main adult pancreatic duct (Fig-7).

•

The main pancreatic duct drains along with the common bile duct at the

major duodenal papilla.

Page 10 of 85

Fig. 7: Eventually, the ventral pancreatic duct and the distal part of the dorsal

pancreatic duct fuse to form the main adult pancreatic duct. The main pancreatic duct

drains along with the common bile duct at the major duodenal papilla.

References: Ankur Arora

•

The ventral duct downstream from the fusion point is called the duct of

Wirsung (Fig-8).

•

The downstream dorsal duct is known as the duct of Santorini or accessory

duct. The accessory duct may contribute some drainage through the minor

papilla.

Page 11 of 85

Fig. 8: The adult pancreatic duct forms from the entire ventral and distal dorsal

pancreatic duct. The ventral duct downstream from the fusion point is called the

duct of Wirsung whilst the downstream dorsal duct is known as the duct of Santorini

(accessory duct). The accessory duct may contribute some drainage through the minor

papilla.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

NORMAL ANATOMY

The foundation stone of Medicine...

•

In 60% of the population, the ventral duct (of Wirsung) serves as the main

channel for drainage of the exocrine pancreatic secretions, although the

Page 12 of 85

accessory duct (of Santorini) drains part of the pancreatic head at the minor

papilla (Fig-9).

•

In 30% of the population the opening of the accessory Santorini duct at the

minor papilla involutes and the pancreas drains solely via the major papilla

(Fig-9).

•

In 10% of individuals the dorsal and ventral pancreatic ducts fail to fuse and

drain separately at the minor and major papilla.

Fig. 9: (1A-B) In 60% of the population, the ventral duct (of Wirsung) serves as the

main channel for drainage, although the accessory duct of Santorini drains part of the

pancreatic head at the minor papilla. (2A-B) In 30% of the population the opening of the

accessory Santorini duct at the minor papilla involutes and the pancreas drains solely

via the major papilla.

Page 13 of 85

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

The normal pancreatic duct exhibits smooth margins and measures 2-3 mm

in caliber. The caliber of the duct tapers slightly from the pancreatic head to

the tail.

VARIANT PANCREATIC DUCT ANATOMY

God loves variety...

•

The pancreatic duct course varies greatly but is most commonly a

descending course (50% of cases) (Fig-10).

Fig. 10: In 50% of population, the pancreatic duct shows a descending course.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 14 of 85

•

Other courses include vertical (Fig-11), sigmoid (Fig-12), undulating

(Fig-13), and loop (Fig-14) configurations.

Fig. 11: Variations in the course of the pancreatic duct. Drawing and 2D-thick slab

MRCP image showing vertical configuration of the pancreatic duct.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 15 of 85

Fig. 12: Variations in the course of the pancreatic duct. Drawing and 2D-thick slab

MRCP image showing sigmoid configuration of the pancreatic duct.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 16 of 85

Fig. 13: Variations in the course of the pancreatic duct. Drawing and 2D-thick slab

MRCP image showing undulating pancreatic duct.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 17 of 85

Fig. 14: Variations in the course of the pancreatic duct. Drawing and thick-slab (2D)

MRCP image showing LOOP configuration of the pancreatic duct.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

It is important to be familiar with the various courses of the pancreatic duct

and not to mistake them for pathologic conditions such as extrinsic masseffect from neoplastic lesions.

•

When the pancreatic duct is oriented vertically, it may be confused with the

extrahepatic bile duct.

•

At the point of embryologic fusion of the ducts of Santorini and Wirsung in

the pancreatic neck, the duct may narrow slightly or demonstrate a loop.

These are normal variations and should not be confused with a stricture.

VARIANT MORPHOLOGY (SHAPE & CONTOUR)

Page 18 of 85

•

Due to embryological development, the head of pancreas comes in many

shapes and sizes, some of which are difficult to differentiate from local

mass.

•

Conventionally, the head and neck of the normal pancreas shows a gentle

near-vertical convexity along its lateral margin. However, approximately 35%

of population show variations in the pancreatic shape and contour (Fig-15).

•

These variants are seen as discrete pancreatic lobulations from the head

and the neck region and can potentially be misinterpreted as a pancreatic

mass.

•

On cross-sectional imaging, hey are seen as outpouchings of the gland

more than 1 cm beyond the anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery.

•

These are primarily of three main types. In type I variants, the lobule

is oriented anteriorly; in type II, posteriorly; and in type Ill, horizontally

(Figs-15,16).

Fig. 15: Pancreatic head configurations. Drawings illustrate the normal appearance

of the pancreatic head i.e a gentle near-vertical convexity lateral to the superior

Page 19 of 85

pancreaticoduodenal artery, and the three variant (pseudomass) appearances. All

three variants show discrete lobulations of normal pancreatic tissue lateral to the

anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery. In type I variants, the lobule is oriented

anteriorly; in type II, posteriorly; and in type III, horizontally.

References: Ankur Arora

Fig. 16: Representative axial CECT image of normal head and neck of pancreas and

three common morphological variants. Type-I variant is seen as a lobulation seen

projecting anteriorly on either side of the artery. Type-II variant is seen as a posterior

lobulation inferolateral to the artery. Type-III variant is seen as horizontally oriented

pancreatic lobulation.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

TUBER OMENTALE:

Another intriguing variant of pancreatic shape is an unusual prominence on the anterior

surface of the pancreas referred to as tuber omentale.

Page 20 of 85

It refers to a well-marked prominence along the anterior surface of the pancreas at

the head-neck junction, that abuts against the posterior surface of the lesser omentum

(Fig-17).

Fig. 17: Pancreatic tuber omentale. Drawing illustrates typical tuber omentale

morphology i.e. a well-marked prominence along the anterior surface of the pancreas

at the head-neck junction, that abuts against the posterior surface of the lesser

omentum.

References: Ankur Arora

Page 21 of 85

Fig. 18: Tuber Omentale. Contiguous axial CECT sections showing uncommon

pancreatic variant (tuber omentale) simulating a true pancreatic neoplasm.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

It is imperative to be aware about this unusual normal variant which should not be

misinterpreted as a pancreatic neoplasm (Fig-18).

Knowledge of the embryologic development, normal and variant anatomy of the pancreas

and its ductal system is imperative for understanding and identifying a wide group of

congenital disorders and anomalies of the pancreas.

Page 22 of 85

Imaging findings OR Procedure details

Pancreatic developmental malformations can be divided into: migration anomalies, fusion

anomalies, and duplication anomalies. Ectopic pancreas and annular pancreas represent

migration anomalies. Pancreas contour variations, including a pancreas divisum and a

variable lateral contour of the pancreatic head, represent fusion anomalies, whilst a bifid

tail of the pancreas represents a type of duplication anomaly.

The spectrum of variants and anomalies discussed include:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

Dorsal Agenesis - complete and partial

Annular pancreas - complete and partial

Circumportal pancreas (portal annular pancreas)

Arterial annular pancreas

Pancreas divisum

Ansa pancreatica

Anomalous pancreato-biliary junction (ABPJ)

Santorinicele & Wirsungocele

Bifid tail of the pancreas

Ectopic pancreas

Intra-pancreatic accessory spleen

Congenital pancreatic cysts

AGENESIS OF DORSAL PANCREAS

•

A a rare congenital anomaly of the pancreas with limited reports in literature

(Fig-19).

•

It represents embryological failure of the dorsal bud to form the body and tail

of the pancreas.

•

The developmental failure or regression of the dorsal pancreatic bud can be

either complete or partial.

Page 23 of 85

Fig. 19: Agenesis of Dorsal Pancreas

References: Ankur Arora

•

Complete agenesis is extremely rare and is characterised by complete

absence of the neck, the body and the tail of the pancreas along with

missing accessory duct of Santorini and minor papilla (Fig-20).

•

In contrast, in partial agenesis the pancreatic body is of variable size, a

remnant of the accessory duct of Santorini exists and the minor papilla is

present.

Page 24 of 85

Fig. 20: In partial agenesis, the pancreas body is of varied size, a remnant of the

accessory duct exists and the minor papilla is present. In complete agenesis, the neck,

body and tail of the pancreas are absent, as are the accessory duct and the minor

duodenal papilla

References: Ankur Arora

•

Generally, these patients remain asymptomatic but some of them manifest

abdominal pain, pancreatitis, or diabetes mellitus.

•

The cause of pancreatitis is contentious; however, dysfunction of the

sphincter of Oddi has been held responsible.

•

As the bulk of the insulin-producing beta cells are normally located in the

pancreatic body and tail, as many as 50% of those with dorsal agenesis

manifest hyperglycemia.

•

On cross-sectional imaging, it manifests as a short truncated pancreas with

absent pancreatic tissue ventral to the splenic vein (Fig-21, 22).

•

There may be associated pseudotumoral enlargement of the pancreatic

head. MRCP can aid in differentiating the partial subtype form complete

agenesis.

Page 25 of 85

Fig. 21: CECT abdomen in a patient with partial dorsal agenesis showing near total

absence of pancreatic body and tail, with a relatively normal sized pancreatic head,

uncinate and neck of pancreas. Distal pancreatic bed is filled with small bowel which is

abutting the splenic vein (dependent intestine sign).

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Fig. 22: Unenhanced fat-saturated T1-weighted MR images reveal normal sized

pancreatic head and uncinate process with absent dosral pancreas (neck, body & tail)

in keeping with complete dorsal agenesis.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

It is crucial to distinguish agenesis of the pancreas from atrophy and

lipomatous replacement of the pancreas secondary to chronic pancreatitis.

Page 26 of 85

Dependent stomach and/or dependent intestine signs are useful imaging

manifestations on cross-sectional imaging that allow differentiation of dorsal

agenesis from distal lipomatosis (Fig-23).

•

The dependent stomach or dependent intestine sign refers to the distal

pancreatic bed getting filled by stomach or intestine which abut the splenic

vein, while, in case of distal lipomatosis abundant fat tissue is observed

anterior to the splenic vein (Fig-24).

Fig. 23: Dependent stomach and/or dependent intestine signs are useful imaging

manifestations on cross-sectional imaging that allow differentiation of dorsal agenesis

from distal lipomatosis. In case of distal lipomatosis abundant fat tissue is observed

anterior to the splenic vein, while the distal pancreatic bed gets filled by stomach or

intestine (which abut the splenic vein) in patients with congenital dorsal pancreatic

agenesis.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 27 of 85

Fig. 24: In a case of congenital dorsal pancreatic agenesis(A)the distal pancreatic

bed is filled by small bowel which is abutting the splenic vein in keeping with

positive dependent small bowel sign. Whilst, in a patient with distal pancreatic

lipomatosis(B)abundant fat tissue is observed anterior to the splenic vein which

prevents the viscera to abut the splenic vein.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

ANNULAR PANCREAS

•

A rare anomaly with a reported incidence of 1 in 1000 - 20,000.

•

An 'annulus' of pancreatic tissue encircling either completely or incompletely

the second part of duodenum (Fig-25).

Page 28 of 85

Fig. 25: Annular pancreas

References: Ankur Arora

•

The exact etiopathogenesis is contentious; however, the most widely

accepted theory suggests that the tip of the ventral anlage adheres to the

duodenum, with the duodenal rotation resulting in a ring of pancreatic tissue

(Fig-26).

Page 29 of 85

Fig. 26: Lecco's theory of annular pancreas.

References: Ankur Arora

•

Complete annular pancreas most commonly presents early in life as small

bowel obstruction and may be associated with other congenital anomalies

such as Down syndrome, Hirschprung disease, polysplenia and intestinal

malrotation.

•

At times, patients remain asymptomatic until adulthood, and present with

nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain, vomiting, or jaundice.

•

Cross-sectional imaging (CT and MRI) reveal pancreatic tissue encircling

the descending duodenum (Fig-27, 28). MRCP is useful for depicting the

annular duct encircling the duodenum (Fig-29).

Page 30 of 85

Fig. 27: CECT abdomen and fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI in two different patients

showing an annulus of pancreatic parenchyma, from the head of the pancreas,

completely encasing the duodenum.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 31 of 85

Fig. 28: Annular pancreas in an adult patient who presented with features of gastric

outlet obstruction. The pancreatic annulus is causing duodenal obstruction and

upstream gastric distension.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 32 of 85

Fig. 29: Annular duct beautifully delineated on thick-slap 2D MRCP image.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

Incomplete or partial annular pancreas is characterized by incomplete

encasement of the duodenum by the pancreatic annulus, typically showing

a crocodile-jaw configuration. Mostly, the entity is incidentally detected at

imaging (Fig-30).

Page 33 of 85

Fig. 30: Incomplete Annular Pancreas: the duodenum is being partially encircled by

the head of pancreas which exhibits a typical crocodile-jaw appearance, highly specific

sign of partial annular pancreas.

References: Arora A, et al. Crocodile-jaw partial annular pancreas, {Online}. URL:

http://www.eurorad.org/case.php?id=9547. DOI: 10.1594/EURORAD/CASE.9547

•

These patients have a higher incidence of concomitant pancreas divisum,

chronic pancreatitis, gastric outlet obstruction, biliary obstruction and/ or

peptic ulceration. Surgical intervention is indicated only in symptomatic

cases.

CIRCUMPORTAL or PORTAL ANNULAR PANCREAS

•

Portal annular pancreas is an uncommon and under-recognized congenital

anomaly of the pancreas (Fig-31).

•

Portal annular pancreas or circumportal pancreas, as the name suggests,

refers to encirclement of the portal or superior mesenteric vein by an

annulus of pancreatic parenchyma (from the uncinate process) (Fig-32).

Page 34 of 85

Fig. 31: Circumportal(portal annular) pancreas

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

Although debatable, it is believed to be a sequel of anomalous fusion of the

ventral and dorsal pancreatic buds occurring cranially and to the left of the

portal/mesenteric vein.

Page 35 of 85

Fig. 32: Circumportal pancreas, as the name suggests, refers to complete

encasement of the portal or mesenteric vein by an annulus of pancreatic tissue from

the uncinate process.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

In patients with circumportal pancreas, the main pancreatic duct either

traverses anterior to the portal vein (normal course) or at times posterior to

the portal vein (retroportal duct).

•

And, based upon the ductal system, Joseph et al. have classified

circumportal pancreas into: type-I circumportal pancreas: with retroportal

pancreatic duct; type-II having pancreas divisum along with retroportal

pancreatic duct; and, type-III with normal anteportal pancreatic duct. Each

type can be further sub-classified into suprasplenic, infrasplenic, and mixed

based upon the level of the annulus in relation to the splenic vein (Fig-33).

Page 36 of 85

Fig. 33: Classification of circumportal pancreas as proposed by Joseph P et al.

References: Ankur Arora

•

The variant by itself is innocuous and is typically incidentally detected on

cross-sectional imaging performed for other reasons (Fig-34).

•

Although frequently overlooked, a detection rate between 1.14 to 2.5% has

been reported on institutional reveiew of contrast enhanced CT studies of

the abdomen.

Fig. 34: Axial and sagittal CECT showing an annulus of pancreatic parenchyma

completely encasing the portal vein (arrows)in keeping with circumportal pancreas,

incidentally detected in a middle aged female.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

Although mostly asymptomatic, if unrecognized this can have serious

adverse consequences during pancreatic surgery. Its recognition is crucial in

those planned for pancreaticoduodenectomy, as an inadvertent pancreatic

duct injury can result in long-term complications such as pancreatic fistula.

ARTERIAL ANNULAR PANCREAS

•

Highly uncommon variant wherein the pancreatic parenchyma encircles an

anomalous artery, or in other words, an anomalous artery navigates through

the pancreatic parenchyma (Fig-35).

•

Paucity of reports available in literature pertaining to this anomalous variant.

Page 37 of 85

•

Replaced right hepatic artery (from the superior mesenteric trunk) is the

commonest to be associated with arterial annular pancreas (Fig-36).

Fig. 35: Arterial Annular Pancreas

References: Ankur Arora

•

Knowledge of this anomaly is especially important in planning hepatobiliary

and pancreatic surgeries in order to avoid unnecessary complications.

•

Preoperative recognition is extremely crucial in those planned for a

Whipple's procedure as a replaced hepatic artery traversing the pancreatic

head can preclude surgery and render the lesion unresectable.

Page 38 of 85

Fig. 36: Incidentally detected Arterial Annular Pancreas. Axial CECT and coronal MIP

image depicting anomalous course of a replaced right hepatic artery coursing through

the pancreatic parenchyma.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

Preoperative identification can prime the surgeon to preserve the vessel, if

feasible, and consequently avoid fatal hepatic injury.

PANCREAS DIVISUM

•

It is the commonest congenital variant of the pancreatic ductal anatomy.

•

In 60% of the population, the ventral duct serves as the main channel

for drainage of the exocrine pancreatic secretions, although the dorsal

pancreatic duct drains part of the pancreatic head at the minor papilla

(Fig-37). In 30% of the population the opening of the dorsal duct at the

minor papilla involutes and the pancreas drains solely via the major papilla.

In 10% of individuals the dorsal and ventral pancreatic ducts fail to fuse and

drain separately at the minor and major papilla, this type of morphology is

termed pancreas divisum.

Page 39 of 85

Fig. 37: Variant ductal anatomy. In approx. 10% of the general population the ventral

and dorsal ducts fail to unite (pancreas divisum).

References: Ankur Arora

•

Pancreas divisum literally means 'divided pancreas,' wherein the dorsal and

the ventral pancreatic buds fail to fuse by 6-8 weeks of gestation (Fig-38).

•

As a result the dorsal duct (Santorini duct) drains most of the pancreatic

parenchyma through the minor papilla, whereas the ventral duct (duct of

Wirsung) drains a portion of the pancreatic head and uncinate process,

through the major papilla.

Page 40 of 85

Fig. 38: Pancreas divisum

References: Ankur Arora

•

Although most patients with pancreas divisum are asymptomatic, PD

has been considered as a predisposing factor for chronic and recurrent

pancreatitis.

•

Three variants of PD have been described in the literature: type-I: classical

PD: where there is total failure of fusion of the ventral and dorsal ducts;

type-II: PD with absent ventral duct, in which dorsal drainage is dominant

and the ventral duct absent; and type-III: incomplete PD, in which there is

a rudimentary communication present between the two ducts. In majority of

cases of PD, no communication exists between the dorsal and ventral ducts

(Fig-39).

Page 41 of 85

Fig. 39: Types of pancreas divisum

References: Ankur Arora

•

The definitive diagnosis of PD needs cannulation of the minor papilla

at ERCP. ERCP is, however, an invasive procedure with a 5% risk of

iatrogenic pancreatitis. MRCP has proven to be highly sensitive and specific

for depicting pancreas divisum.

•

MRCP shows a dominant dorsal pancreatic duct which shows separate

drainage into the duodenum via the minor papilla. The CBD along with

a rudimentary ventral panceratic duct drains through the major papilla

(Fig-40).

Page 42 of 85

Fig. 40: MRCP images reveal that the pancreatic duct is crossing the CBD and

draining separately at the minor duodenal papilla, whilst, the CBD is draining caudally

at the major duodenal papilla (ampulla of Vater). The ventral duct is not visualized

suggesting type-II pancreas divisum.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

Secretin-enhanced MRCP can further improve the diagnostic accuracy

to show pancreatic divisum. Secretin administration enhances the signalto-noise ratio and improves visualization of the variant ductal anatomy by

increasing the ductal caliber and ductal-fluid content.

•

Visualisation of the main pancreatic duct coursing anterior to CBD and

draining separately into the duodenum on axial CT-images or MR images is

a valuable sign that should raise suspicion for PD.

•

Multi-planar and minimum-intensity-projection reformations on CT are of vital

utility in depicting separate drainage and non-union of the ventral and dorsal

ducts. Soto et al have reported a sensitivity of 90%, specificity of 98%, and a

negative predictive value of up to 98% of depicting PD on MDCT (Fig-41).

Page 43 of 85

Fig. 41: Minimum intensity projection displaying nonunion of the dosral and ventral

pancreatic ducts. There is predominant drainage of the gland through the duct of

Santorini while the ventral duct appears rudimentary.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

ANSA PANCREATICA

•

Ansa pancreatica is a rare congenital variant of the pancreatic ductal system

first described by Dawson and Langman in 1961.

Page 44 of 85

•

It is characterised by an unusual caudally looping 'sigmoid' communication

between the ventral and dorsal ductal systems instead of its direct course

(Fig-42, 43).

Fig. 42: Ansa pancreatica

References: Ankur Arora

•

It is hypothesised to develop from a side branch of the ventral duct that

communicates with the distal part of the accessory duct.

Page 45 of 85

Fig. 43: Ansa pancreatica.

References: Ankur Arora

•

Although contentious, an association of ansa pancreatica with recurrent

pancreatitis - presumably secondary to suboptimal drainage of pancreatic

secretions through the acute-angled accessory duct at the minor papilla, has

been reported in literature (Fig-44).

Page 46 of 85

Fig. 44: Thick-slab (2D) MRCP image reveals a dilated and beaded main pancreatic

duct (thin arrow) with an intra-pancreatic pseudocyst (*)consistent with chronic

pancreatitis. The accessory duct is seen forming an unusual sigmoid-shaped caudal

loop (thick short arrow) in keeping with ansa pancreatica.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

Symptomatic patients may mandate sphincterotomy to improve drainage

of the pancreatic juices. And if repeated sphincterotomies fail, surgical

decompression has been recommended.

ANOMALOUS PANCREATICO-BILIARY JUNCTION (APBJ)

•

Anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction (APBJ) refers to anomalous union of

the pancreatic and bile ducts outside the duodenal wall resulting in a long

common channel (usually > 15-mm) (Fig-45).

•

APBJ is seen in up to 90-100% of cases of congenital choledochal cysts and

is associated with increased risk of pancreatitis, cholangiocarcinoma and

gallbladder carcinoma presumably secondary to biliopancreatic reflux.

Page 47 of 85

Fig. 45: Anomalous pancreatico-biliary junction (APBJ).

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

The presence of a long common channel allows reflux of pancreatic

secretions into the biliary system, possibly resulting in choledochal cyst.

Conversely, reflux of bile into the pancreatic duct can cause relapsing or

chronic pancreatitis

•

MRCP is a non-invasive and accurate imaging method for diagnosing APBJ

(Fig-46).

Page 48 of 85

Fig. 46: A 3-year-old child with congenital choledochal cyst (type-IVA of Todani

classification) with recurrent pancreatitis. Coronal T2w MRI (A) and 3D-MRCP

(B) show dilated intra-and extrahepatic bile ducts and the main pancreatic duct. A

long common channel (arrow) is seen with the bile-duct joining the pancreatic duct

anomalously at an acute angle in keeping with an APBJ.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

The most popular classification of ABPJ is the Komi classification. The

common bile duct joins the pancreatic duct at a right angle in type-I, and

at an acute angle in type-II; and both these types are subdivided into "a"

or "b", according to whether the common channel is dilated or not (the

normal common channel caliber being 3-5 mm). In type-III, APBJ union

is complicated with a patent accessory pancreatic duct, and is further

subclassified into types-IIIa, IIIb, and IIIc (Fig-47).

Page 49 of 85

Fig. 47: Komi classification of ABPJ.

References: Ankur Arora

•

APBJ is considered to be a major risk factor for biliary tract malignancy.

Reflux of pancreatic juice into the biliary tract might induce biliary tract

damage and biliary carcinogenesis.

•

Accordingly, total resection of the extrahepatic bile duct and

hepaticojejunostomy are recommended in patients diagnosed with APBJ

with choledochal cyst (Fig-48).

Page 50 of 85

Fig. 48: A patient with previously operated choledochal cyst shows an APBJ with a

long common channel. Ideally, the entire choledochal cyst along with the pancreaticobiliary maljunction should have been excised. The patient remains a high-risk

candidate for biliary tract malignancy.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

Early diagnosis and early surgical treatment provide a good prognosis with

few complications. In addition, successive follow-up is necessary for early

detection of biliary tract malignancy, especially in patients demonstrating

postoperative complications.

SANTORINICELE & WIRSUNGOCELE

•

Cystic dilatation of the distal dorsal duct, just proximal to the minor papilla, is

termed Santorinicele. And, cystic dilation of terminal ventral pancreatic duct

(Wirsung's duct) is known as Wirsungocele (Fig-49).

Page 51 of 85

•

They are considered analogous to ureteroceles and choledochoceles, and

are believed to result from a combination, either congenital or acquired, of

relative obstruction and weakness of the distal ductal wall.

Fig. 49: Santorinicele & Wirsungocele.

References: Ankur Arora

•

Santorinicele was first described in 1994 by Eisen et al. who reported

four patients with pancreatitis and pancreas divisum accompanied with

Santorinicele on ERCP .

•

Santorinicele has been suggested as a possible cause of relative stenosis of

the accessory papilla.

•

Santorinicele in association with pancreas divisum (unfused dorsal and

ventral ducts) results in high intraductal pressure which is presumably

responsible for recurrent pancreatitis (Fig-50).

Page 52 of 85

Fig. 50: Thick slab (2D) MRCP image shows the pancreas is being drained by the

dorsal duct which is crossing the CBD and draining at the minor duodenal papilla in

keeping with pancreas divisum. In addition, there is focal dilatation of the dorsal duct

near the papilla consistent with Santorinicele.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

Cystic dilation of terminal ventral pancreatic duct (Wirsung's duct) is known

as Wirsungocele. This anatomical abnormality was first described in 2004 as

an incidental finding.

•

Wirsungocele has recently been shown to be associated with acute

recurrent, severe necrotizing pancreatitis and chronic pancreatitis or chronic

pain in abdomen (Fig-51).

Page 53 of 85

Fig. 51: A: Thick-slab (2D) MRCP image in a child with Caroli disease and recurrent

pancreatitis reveals focal cystic dilatation of the ventral duct just before the ampulla in

keeping with Wirsungocele. In addition, a tiny intraluminal filling-defect is seen within

the wirsungocele suggestive of Wirsungolith. It appears hypointense on axial FIESTA

sequence (B).

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

Whether the association of recurrent pancreatitis and Wirsungocele

is causative or incidental remains to be established. Also, the role of

pancreatic endotherapy is also unsubstantiated.

BIFID PANCREATIC TAIL

•

Bifid pancreatic tail (pancreas bifidum), or fish tail pancreas, is a very rare

congenital branching anomaly of the main pancreatic duct (Fig-52).

Page 54 of 85

Fig. 52: Pancreas bifidum

References: Ankur Arora

•

On MRCP or ERCP it manifests as duplication of the major duct in the body

of the pancreas (Fig-53).

•

On cross-sectional imaging, it is identified as division of the pancreatic tail

into separate dorsal and ventral buds. The pancreatic tail does not tend to

reach the splenic hilum when this anomaly is present, a telltale sign of its

presence.

Page 55 of 85

Fig. 53: Thick slab (2D) MRCP depicting bifid main pancreatic duct.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

Bifid tail of the pancreas is a benign congenital variant which is found only

incidentally. The clinical effect and importance of this anomaly remains

uncertain.

ECTOPIC PANCREAS

•

Ectopic pancreas occurs in 0.6%-13.7% of the population.

•

Ectopic pancreas can develop from an anomalous separation of developing

pancreatic anlagen, with bowel wall penetration and subsequent

displacement with longitudinal growth of the intestinal wall, or it can be

Page 56 of 85

due to differentiation of totipotent endodermal cells of intestinal tract into

pancreatic tissue (Fig-54).

Fig. 54: Ectopic pancreas

References: Ankur Arora

•

This ectopic tissue can be found in the stomach (26%-38% of cases),

duodenum (28%-36%), jejunum (16%), Meckel diverticulum, or ileum

(Fig-55).

•

Rarely, it occurs in the colon, esophagus, gallbladder, bile ducts, liver,

spleen, umbilicus, mesentery, mesocolon, or omentum.

•

The ectopic tissue usually measures 0.5-2.0 cm in its largest dimension

(rarely up to 5 cm) and is located in the submucosa in approximately 50% of

cases.

Page 57 of 85

Fig. 55: Axial & sagittal CECT showing a submucosal nodule within the stomach

though to be a neoplasm was subjected to endoscopic US guided fine-needleaspiration and diagnosed to be ectopic pancreas.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

Ectopic pancreas can present as a submucosal mass and simulate tumours

such as GIST and lieomyoma.

•

If the ectopic pancreatic tissue is functional it can be involved with the same

inflammatory or neoplastic process as the normal pancreas.

•

Ectopic pancreas in the gastrointestinal tract is usually asymptomatic,

although complications such as stenosis, ulceration, bleeding, and

intussusception may develop.

INTRAPANCREATIC ACCESSORY SLPEEN (IPAS)

•

Rarely, the splenic rest cells get trapped and grow within the pancreatic tail

to form an intra-pancreatic accessory spleen (IPAS).

•

The frequency is 1% to 2% of all accessory spleens that may be found in

about 7% to 15% of the population according to studies from autopsies.

The most common location of an accessory spleen is at the splenic hilum,

followed by adjacent to, and within the pancreatic tail (Fig-56).

Page 58 of 85

Fig. 56: Inatra-pancreatic Accessory Spleen

References: Ankur Arora

•

Intra-pancreatic accessory spleen usually poses no clinical problem and

therefore merits no specific treatment.

•

The clinical importance lies in the fact that it can be misdiagnosed as a

pancreatic neoplasm and subjected to unnecessary surgery or biopsy. In the

past, majority of the cases were misdiagnosed as pancreatic tumours and

subjected to unnecessary surgery.

•

A high index of clinical suspicion based on the classic location and typical

imaging findings can yield an apt pre-operative diagnosis thus avoiding

unnecessary intervention.

•

IPAS exhibits quite similar imaging characteristics to the proper spleen

on the unenhanced and dynamic contrast enhanced CT and MR imaging,

and in general remain brighter than the pancreas on all three dynamic CT

phases (Fig-57). On MRI, IPAS follows similar signal intensity as that of the

main spleen (Fig-58).

Page 59 of 85

Fig. 57: The nodular accessory spleen within the pancreatic tail displaying attenuation

and enhancement characteristics similar to those of the main spleen on the arterial and

the venous phase scans. The lesion can be easily mistaken for a pancreatic neoplasm

and subjected to unnecessary biopsy or surgery.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 60 of 85

Fig. 58: With respect to the pancreas the intrapancreatic nodule (IPAS) is hypointense

on T1-weighted and hyperintense on T2-weighted images, whilst it displays similar

signal intensity as that of the adjacent spleen.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

In doubtful cases, con#rmation can be achieved by means of SPECT with

technetium 99-labelled RBCs as the tracer is readily trapped by the splenic

tissue.

•

Alternately, contrast-enhanced ultrasonography using microgranules can be

utilized as the granules during the late phase are retained almost exclusively

by the hepatosplenic parenchyma, thus allowing the distinction from a

pancreatic tumor.

CONGENITAL PANCREATIC CYSTS

•

Congenital pancreatic cysts are exceedingly rare.

•

When present, they are mostly multiple, and almost all are associated with

multisystem congenital diseases (Fig-59).

Page 61 of 85

Fig. 59: Congenital pancreatic cysts.

References: Ankur Arora

•

Solitary congenital cysts of the pancreas are rare.

•

They have a female predilection and typically manifest as an asymptomatic

palpable mass.

•

Uncommonly, patients present with epigastric pain, discomfort, jaundice and

vomiting due to their mass effect on adjacent structures.

•

von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease: pancreatic cysts are relatively common

in VHL, and involvement can range from a single cyst to cystic replacement

of the gland. Peripheral calcifications may also be present. Pancreatic

cysts themselves are innocuous, however, may be associated with other

pancreatic neoplasms such as microcystic serous adenoma and endocrine

tumors (Fig-60).

Page 62 of 85

Fig. 60: An 8-year old boy with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Axial CECT image shows

multiple cysts replacing the pancreatic parenchyma in keeping with congenital cystic

replacement of the pancreas.

References: Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver

and Biliary Sciences - New Delhi/IN

•

Cystic fibrosis: typically manifests as fatty replacement of the pancreas,

but calcifications and cysts may also be found. Cysts can be single or

multiple; most are microscopic, but infrequently may reach up to several

centimeters in size.

•

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): Extrarenal

cysts may be encountered in liver, pancreas, spleen and, ovaries.

Pancreatic cysts vary from microscopic to several centimeters in diameter.

Page 63 of 85

Conclusion

Recognition of variant & anomalous anatomy on imaging provides a great learning

platform for reviewing common morphology and embryogenesis of the pancreas, and

yields insight into the potential medical, radiologic, and surgical implications.

These anatomic variants and developmental anomalies of the pancreas can be important;

some of which can pose medical problems or a diagnostic challenge, while others may

render surgical treatment more intricate.

Familiarity with the imaging features is important to establish the correct diagnosis and

determine appropriate treatment, which is critical to avoid life-threatening complications.

**For succinct review please refer Figs: 61-73

Page 64 of 85

Images for this section:

Fig. 61: Agenesis of dorsal pancreas

© Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver and Biliary

Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 65 of 85

Fig. 62: Complete annular pancreas

© Ankur Arora

Page 66 of 85

Fig. 63: Incomplete (partial) Annular Pancreas

© Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver and Biliary

Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 67 of 85

Fig. 64: Portal annular (circumportal) pancreas

© Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver and Biliary

Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 68 of 85

Fig. 65: Arterial Annular Pancreas

© Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver and Biliary

Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 69 of 85

Fig. 66: Pancreas Divisum

© Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver and Biliary

Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 70 of 85

Fig. 67: Ansa pancreatica

© Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver and Biliary

Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 71 of 85

Fig. 68: Anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction (APBJ)

© Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver and Biliary

Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 72 of 85

Fig. 69: Santorinicele & Wirsungocele

© Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver and Biliary

Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 73 of 85

Fig. 70: Pancreas bifidum

© Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver and Biliary

Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 74 of 85

Fig. 71: Ectopic pancreas

© Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver and Biliary

Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 75 of 85

Fig. 72: Intrapancreatic accessory spleen

© Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver and Biliary

Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 76 of 85

Fig. 73: Congenital Pancreatic Cysts

© Radiodiagnosis, Insitute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, Insitute of Liver and Biliary

Sciences - New Delhi/IN

Page 77 of 85

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

Alexander LF. Congenital pancreatic anomalies, variants, and

conditions. Radiol Clin North Am. 2012 May;50(3):487-98. doi: 10.1016/

j.rcl.2012.03.006.

Tadokoro H, Takase M, Nobukawa B. Development and congenital

anomalies of the pancreas. Anat Res Int. 2011;2011:351217. doi:

10.1155/2011/351217.

John M. Howard (Toledo, Ohio). History of the Pancreas. http://

pancreasclub.com/home/pancreas.

Hernandez-Jover D, Pernas JC, Gonzalez-Ceballos S, Lupu I, Monill JM,

Pérez C. Pancreatoduodenal junction: review of anatomy and pathologic

conditions. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011 Jul;15(7):1269-81. doi: 10.1007/

s11605-011-1443-8.

Nijs EL, Callahan MJ. Congenital and developmental pancreatic anomalies:

ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging

features. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2007 Oct;28(5):395-401.

Mortelé KJ, Rocha TC, Streeter JL, Taylor AJ. Multimodality imaging of

pancreatic and biliary congenital anomalies. Radiographics. 2006 MayJun;26(3):715-31.

Yu J, Turner MA, Fulcher AS, Halvorsen RA. Congenital anomalies

and normal variants of the pancreaticobiliary tract and the pancreas in

adults: part 2,Pancreatic duct and pancreas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006

Dec;187(6):1544-53.

Benya EC. Pancreas and biliary system: imaging of developmental

anomalies and diseases unique to children. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002

Dec;40(6):1355-62.

Tang Y, Yamashita Y, Abe Y, Namimoto T, Tsuchigame T, Takahashi

M. Congenital anomalies of the pancreaticobiliary tract: findings on MR

cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) using half-Fourier-acquisition singleshot turbo spin-echo sequence (HASTE). Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2001

Sep-Oct;25(5):423-31.

Nijs E, Callahan MJ, Taylor GA. Disorders of the pediatric pancreas: imaging

features. Pediatr Radiol. 2005 Apr;35(4):358-73; quiz 457.

Durie PR. Inherited and congenital disorders of the exocrine pancreas.

Gastroenterologist. 1996 Sep;4(3):169-87.

Brambs HJ. [Developmental anomalies and congenital diseases of the

pancreas]. Radiologe. 1996 May;36(5):381-8.

Fulcher AS, Turner MA. MR pancreatography: a useful tool for evaluating

pancreatic disorders. Radiographics. 1999 Jan-Feb;19(1):5-24; discussion

41-4; quiz 148-9.

Rizzo RJ, Szucs RA, Turner MA. Congenital abnormalities of the pancreas

and biliary tree in adults. Radiographics. 1995 Jan;15(1):49-68; quiz 147-8.

Page 78 of 85

15. Roberts IM. Disorders of the pancreas in children. Gastroenterol Clin North

Am. 1990 Dec;19(4):963-73.

16. Arora A, Sandip S, Mukund A, Patidar Y. It is short-but so what! Indian J

Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Sep;16(5):858-9. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.100687.

17. Karcaaltincaba M. CT differentiation of distal pancreas fat replacement and

distal pancreas agenesis. Surg Radiol Anat. 2006 Dec;28(6):637-41.

18. Mohapatra M, Mishra S, Dalai PC, Acharya SD, Nahak B, Ibrarullah M, et al.

Imaging findings in agenesis of the dorsal pancreas. Report of three cases.

JOP. 2011 Dec 22;13(1):108-14.

19. Lång K, Lasson A, Müller MF, Thorlacius H, Toth E, Olsson R. Dorsal

agenesis of the pancreas - a rare cause of abdominal pain and insulindependent diabetes. Acta Radiol. 2011 Dec 2. [Epub ahead of print] PMID:

22139719.

20. Shimodaira M, Kumagai N, Sorimachi E, Hara M, Honda K. Agenesis of

the dorsal pancreas: a rare cause of diabetes. Intern Emerg Med. 2012

Feb;7(1):83-4. doi: 10.1007/s11739-011-0620-9.

21. Pasaoglu L, Vural M, Hatipoglu HG, Tereklioglu G, Koparal S. Agenesis of

the dorsal pancreas. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 May 14;14(18):2915-6.

22. Fukuoka K, Ajiki T, Yamamoto M, Fujiwara H, Onoyama H, Fujita T,

Katayama N,Mizuguchi K, Ikuta H, Kuroda Y, Hanioka K. Complete

agenesis of the dorsal pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg.

1999;6(1):94-7.

23. Joo YE, Kang HC, Kim HS, Choi SK, Rew JS, Chung MY, Kim SJ. Agenesis

of the dorsal pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. Korean J

Intern Med. 2006 Dec;21(4):236-9.

24. Sandrasegaran K, Patel A, Fogel EL, Zyromski NJ, Pitt HA. Annular

pancreas in adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009 Aug;193(2):455-60. doi:

10.2214/AJR.08.1596.

25. Pansini M, Magerkurth O, Haecker FM, Sesia SB. Annular pancreas

associated with duodenal obstruction. BMJ Case Rep. 2012 Sep 17;2012.

doi:pii: bcr2012006855. 10.1136/bcr-2012-006855.

26. Arora A, Mukund A, Thapar S, Jain D. Crocodile-jaw pancreas. Indian J

Gastroenterol. 2012 Sep;31(5):281. doi: 10.1007/s12664-012-0231-z.

27. Arora A. Crocodile-jaw partial annular pancreas, {Online}. DOI: 10.1594/

EURORAD/CASE.9547.

28. Jarboui S, Fakhfekh S, Jarraya H, Ben Moussa M, Zaouche A. Annular

pancreas in adults. Tunis Med. 2011 Oct;89(10):804-5.

29. Patra DP, Basu A, Chanduka A, Roy A. Annular pancreas: a rare cause of

duodenal obstruction in adults. Indian J Surg. 2011 Apr;73(2):163-5. doi:

10.1007/s12262-010-0150-0.

30. Siew JX, Yap TL, Phua KB, Kader A, Fortier MV, Ong C. Annular Pancreas:

A Rare Cause of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in a Child. J Pediatr

Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012 Aug 3. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 22868685.

31. Chen YC, Yeh CN, Tseng JH. Symptomatic adult annular pancreas. J Clin

Gastroenterol. 2003 May-Jun;36(5):446-50.

Page 79 of 85

32. Jadvar H, Mindelzun RE. Annular pancreas in adults: imaging features in

seven patients. Abdom Imaging. 1999 Mar-Apr;24(2):174-7.

33. Jang JY, Chung YE, Kang CM, Choi SH, Hwang HK, Lee WJ. Two cases of

portal annular pancreas. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2012 Jul;60(1):52-5.

34. Ishigami K, Tajima T, Nishie A, Asayama Y, Kakihara D, Nakayama T,

Shirabe K, Taketomi A, Nakamura M, Takahata S, Ito T, Honda H. The

prevalence of circumportal pancreas as shown by multidetector-row

computed tomography. Insights Imaging. 2011 Aug;2(4):409-414.

35. Joseph P, Raju RS, Vyas FL, Eapen A, Sitaram V. Portal annular pancreas.

A rare variant and a new classification. JOP. 2010 Sep 6;11(5):453-5.

36. Karasaki H, Mizukami Y, Ishizaki A, Goto J, Yoshikawa D, Kino S,

Tokusashi Y, Miyokawa N, Yamada T, Kono T, Kasai S. Portal annular

pancreas, a notable pancreatic malformation: frequency, morphology, and

implications for pancreatic surgery. Surgery. 2009 Sep;146(3):515-8.

37. Kin T, Shapiro J. Partial dorsal agenesis accompanied with circumportal

pancreas in a donor for islet transplantation. Islets. 2010 MayJun;2(3):146-8. doi: 10.4161/isl.2.3.11715.

38. Izuishi K, Wakabayashi H, Usuki H, Suzuki Y. Anomalous annular

pancreas surrounding the superior mesenteric vessel. ANZ J Surg. 2010

May;80(5):376-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05287.x.

39. Furukawa H, Shimada K, Iwata R, Moriyama N. A replaced common

hepatic artery running through the pancreatic parenchyma. Surgery. 2000

Jun;127(6):711-2.

40. Hosokawa I, Shimizu H, Nakajima M, Yoshidome H, Ohtsuka M, Kato A,

Yoshitomi H, Furukawa K, Takeuchi D, Takayashiki T, Kuboki S, Suzuki D,

Miyazaki M. [A case of pancreaticoduodenectomy for duodenal carcinoma

with a replaced common hepatic artery running through the pancreatic

parenchyma]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2012 Nov;39(12):1963-5.

41. Yamamoto S, Kubota K, Rokkaku K, Nemoto T, Sakuma A. Disposal

of replaced common hepatic artery coursing within the pancreas during

pancreatoduodenectomy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2005;35(11):984-7.

42. Arora A. Pancreas divisum: depiction with MDCT and MRI. DOI: 10.1594/

EURORAD/CASE.9509.

43. Mosler P, Akisik F, Sandrasegaran K, Fogel E, Watkins J, Alazmi W,

Sherman S, Lehman G, Imperiale T, McHenry L. Accuracy of magnetic

resonance cholangiopancreatography in the diagnosis of pancreas divisum.

Dig Dis Sci. 2012 Jan;57(1):170-4. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1823-7.

44. Pezzilli R, Calculli L, Cariani G, Imbrogno A, Fabbri D. Acute recurrent

pancreatitis and pancreas divisum: appearances can be deceiving. Dig Liver

Dis. 2012 Nov;44(11):965-6. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.05.020.

45. Rana SS, Gonen C, Vilmann P. Endoscopic ultrasound and pancreas

divisum. JOP. 2012 May 10;13(3):252-7.

46. Anderson SW, Soto JA. Pancreatic duct evaluation: accuracy of portal

venous phase 64 MDCT. Abdom Imaging. 2009 Jan-Feb;34(1):55-63. doi:

10.1007/s00261-008-9396-4.

Page 80 of 85

47. Soto JA, Lucey BC, Stuhlfaut JW. Pancreas divisum: depiction with multidetector row CT. Radiology. 2005 May;235(2):503-8.

48. Manfredi R, Costamagna G, Brizi MG, Maresca G, Vecchioli A, Colagrande

C, Marano P. Severe chronic pancreatitis versus suspected pancreatic

disease: dynamic MR cholangiopancreatography after secretin stimulation.

Radiology. 2000 Mar;214(3):849-55.

49. Anderson SW, Zajick D, Lucey BC, Soto JA. 64-detector row computed

tomography: an improved tool for evaluating the biliary and pancreatic

ducts? Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2007 Nov-Dec;36(6):258-71.

50. Ayari H, Rebii S, Ayari M, Hasni R, Zoghlami A. [Ansa pancreatica: a rare

cause of acute pancreatitis]. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13:33.

51. Halilo#lu N, Erden A. Ansa pancreatica: a rare pancreas ductal variation.

Turk J Gastroenterol. 2008 Dec;19(4):296-7.

52. Bhasin DK, Rana SS, Nanda M, Gupta R, Nagi B, Wig JD. Ansa pancreatica

type of ductal anatomy in a patient with idiopathic acute pancreatitis. JOP.

2006 May 9;7(3):315-20.

53. Tanaka T, Ichiba Y, Miura Y, Itoh H, Dohi K. Variations of the pancreatic

ducts as a cause of chronic alcoholic pancreatitis; ansa pancreatica. Am J

Gastroenterol. 1992 Jun;87(6):806.

54. Arora A, Mukund A, Thapar S, Alam S. Anomalous Pancreaticobiliary

Junction (APBJ). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012 Apr 24. [Epub ahead of

print] PMID: 22543435.

55. Ono S, Fumino S, Iwai N. Diagnosis and treatment of pancreaticobiliary

maljunction in children. Surg Today. 2011 May;41(5):601-5. doi: 10.1007/

s00595-010-4492-9.

56. Funabiki T, Matsubara T, Miyakawa S, Ishihara S. Pancreaticobiliary

maljunction and carcinogenesis to biliary and pancreatic malignancy.

Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009 Jan;394(1):159-69. doi: 10.1007/

s00423-008-0336-0.

57. Itoh S, Fukushima H, Takada A, Suzuki K, Satake H, Ishigaki T. Assessment

of anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction with high-resolution

multiplanar reformatted images in MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006

Sep;187(3):668-75.

58. Sugiyama M, Haradome H, Takahara T, Izumisato Y, Abe N, Masaki

T, Mori T, Hachiya J, Atomi Y. Biliopancreatic reflux via anomalous

pancreaticobiliary junction. Surgery. 2004 Apr;135(4):457-9.

59. Irie H, Honda H, Jimi M, Yokohata K, Chijiiwa K, Kuroiwa T, Hanada

K, Yoshimitsu K, Tajima T, Matsuo S, Suita S, Masuda K. Value of MR

cholangiopancreatography in evaluating choledochal cysts. AJR Am J

Roentgenol. 1998 Nov;171(5):1381-5.

60. Sugiyama M, Baba M, Atomi Y, Hanaoka H, Mizutani Y, Hachiya J.

Diagnosis of anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction: value of magnetic

resonance cholangiopancreatography. Surgery. 1998 Apr;123(4):391-7.

61. Arora A, Mukund A, Thapar S, Alam S. Anomalous Pancreaticobiliary

Junction (APBJ). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012 Apr 24. [Epub ahead of

print] PMID: 22543435.

Page 81 of 85

62. Khan SA, Chawla T, Azami R. Recurrent acute pancreatitis due to a

santorinicele in a young patient. Singapore Med J. 2009 May;50(5):e163-5.

63. Nam KD, Joo KR, Jang JY, Kim NH, Lee SK, Dong SH, Kim HJ, Kim BH,

Chang YW, Lee JI, Chang R. A case of santorinicele without pancreas

divisum: diagnosis with multi-detector row computed tomography. J Korean

Med Sci. 2006 Apr;21(2):358-60.

64. Manfredi R, Costamagna G, Brizi MG, Spina S, Maresca G, Vecchioli A,

Mutignani M, Marano P. Pancreas divisum and "santorinicele": diagnosis

with dynamic MR cholangiopancreatography with secretin stimulation.

Radiology. 2000Nov;217(2):403-8.

65. Peterson MS, Slivka A. Santorinicele in pancreas divisum: diagnosis with

secretin-stimulated magnetic resonance pancreatography. Abdom Imaging.

2001 May-Jun;26(3):260-3.

66. Joo KR, Bang SJ, Shin JW, Kim DH, Park NH. Santorinicele containing a

pancreatic duct stone in a patient with incomplete pancreas divisum. Yonsei

Med J. 2004 Oct 31;45(5):952-5.

67. Gupta R, Lakhtakia S, Tandan M, Santosh D, Rao GV, Reddy DN.

Recurrent acute pancreatitis and Wirsungocele. A case report and review of

literature. JOP. 2008 Jul 10;9(4):531-3.

68. Coelho DE, Ardengh JC, Lima-Filho ER, Coelho JF. Different clinical

aspects of Wirsungocele: case series of three patients and review of

literature. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2011 Sep;41(3):230-3.

69. Dinter D, Löhr JM, Neff KW. Bifid tail of the pancreas: benign bifurcation

anomaly. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007 Nov;189(5):W251-3.

70. Low G, Panu A, Millo N, Leen E. Multimodality imaging of neoplastic and

nonneoplastic solid lesions of the pancreas. Radiographics. 2011 JulAug;31(4):993-1015. doi: 10.1148/rg.314105731.

71. Kikuchi K, Nomiyama T, Miwa M, Harasawa S, Miwa T. Bifid tail of

the pancreas: a case presenting as a gastric submucosal tumor. Am J

Gastroenterol. 1983 Jan;78(1):23-7.

72. Uomo G, Manes G, D'Anna L, Laccetti M, Di Gaeta S, Rabitti PG.

Fusion and duplication variants of pancreatic duct system. Clinical and

pancreatographic evaluation. Int J Pancreatol. 1995 Feb;17(1):23-8.

73. Ross BA, Jeffrey RB Jr, Mindelzun RE. Normal variations in the lateral

contour of the head and neck of the pancreas mimicking neoplasm:

evaluation with dual-phase helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996

Apr;166(4):799-801.

74. Yang DM, Kim HC, Jin W, Ryu CW, Ryu JK, Nam DH. Unusual ventral

contour of the pancreatic head mimicking a pancreatic tumor as depicted on

sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2008 Dec;27(12):1791-3.

75. Winestone M., Joffe S.A., Kagen A., Wayne M. Congenital anomalies of the

pancreas in adults: findings on CT and MR imaging. ESGAR 2011. EE-181.

DOI: 10.5444/esgar2011/EE-181.

Page 82 of 85

Images for this section:

Fig. 75: ESR_ECR

© Ankur Arora

Page 83 of 85

Personal Information

Ankur Arora, MD, DNB, FRCR, EDiR

Assistant Professor (Radiology/ Interventional Radiology)

Institute of Liver & Biliary Sciences (ILBS)

New Delhi, India

Email: [email protected]

Acknowledgements

Fig. 75: ESR_ECR

References: Ankur Arora

Page 84 of 85

Images for this section:

Fig. 74: ILBS

© Ankur Arora

Page 85 of 85

© Copyright 2026