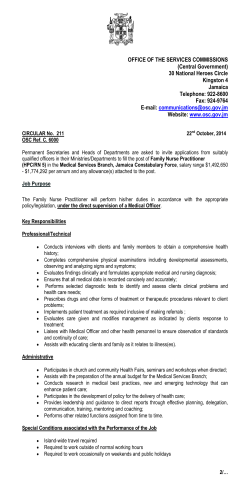

The introduction of the nurse practitioner in general practice