BIAN white paper – Cloud enabling the banking industry v1_0

Banking Industry

Architecture Network

White Paper

Cloud enabling

the Banking Industry

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

Organization

Authors

Role

Name

Company

BIAN Lead Architect

Guy Rackham

Chief Architect, SWG FS

Santhosh Kumaran

IBM

Industry Technology

Strategist - Banking

Victor Dossey

Microsoft

Status

Status

Date

Actor

Comment / Reference

DRAFT

Approved

Version

No

Comment / Reference

Date

0.8

Updated diagrams and first comments

05-06-2014

0.96

Updated text with comments and reorganising it

17-06-2014

0.97

Updated text after input

07-08-2014

0.98

Updated the diagrams and small changes in text

11-08-2014

1.0

Added last comments

04-09-2014

Page 2 of 26

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

Copyright

© Copyright 2014 by BIAN Association. All rights reserved.

THIS DOCUMENT IS PROVIDED "AS IS," AND THE ASSOCIATION AND ITS

MEMBERS, MAKE NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR

IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO, WARRANTIES OF

MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE,

NONINFRINGEMENT, OR TITLE; THAT THE CONTENTS OF THIS DOCUMENT

ARE SUITABLE FOR ANY PURPOSE; OR THAT THE IMPLEMENTATION OF

SUCH CONTENTS WILL NOT INFRINGE ANY PATENTS, COPYRIGHTS,

TRADEMARKS OR OTHER RIGHTS.

NEITHER THE ASSOCIATION NOR ITS MEMBERS WILL BE LIABLE FOR ANY

DIRECT, INDIRECT, SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES

ARISING OUT OF OR RELATING TO ANY USE OR DISTRIBUTION OF THIS

DOCUMENT UNLESS SUCH DAMAGES ARE CAUSED BY WILFUL

MISCONDUCT OR GROSS NEGLIGENCE.

THE FOREGOING DISCLAIMER AND LIMITATION ON LIABILITY DO NOT APPLY

TO, INVALIDATE, OR LIMIT REPRESENTATIONS AND WARRANTIES MADE BY

THE MEMBERS TO THE ASSOCIATION AND OTHER MEMBERS IN CERTAIN

WRITTEN POLICIES OF THE ASSOCIATION.

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Page 3 of 26

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

Table of Contents

1

2

3

Background .................................................................................................................. 6

1.1

The Opportunity – Cloud Enabling the Banking Industry ........................................... 6

1.2

Defining the ‘Cloud’ .................................................................................................. 7

1.3

Layered Access to the ‘Cloud’ – the context for using BIAN ..................................... 8

1.4

Business Model Transformation using the Cloud ...................................................... 9

Cloud enablement using BIAN ...................................................................................10

2.1

A new conceptual model to define the Cloud configuration ......................................10

2.2

Using Service Domains to Organize Cloud Services ...............................................13

An Example using BIAN to Specify Cloud SaaS .......................................................19

3.1

Example - account opening .....................................................................................19

3.2

Solution Design – a simplified example ...................................................................20

3.3

Future Development Needs & Opportunities............................................................24

4

Summary ......................................................................................................................25

5

Conclusion...................................................................................................................26

Page 4 of 26

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

Table of Figures

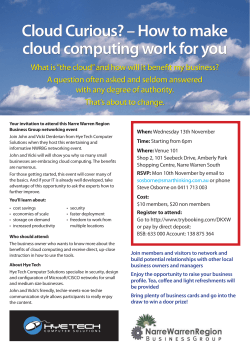

Diagram 1: Simple Cloud central utility service, brokered to multiple bank subscribers ........12

Diagram 2: BIAN service domains & service operations as an enterprise service bus

directory ...............................................................................................................................14

Diagram 3: BIAN servics Mapped to host data structures .....................................................15

Diagram 4: BIAN serviecs constrain access, creating an application container ....................17

Diagram 5: Service Domains involved in the offer process ...................................................21

Diagram 6: Offer Management Component Structure ...........................................................22

Diagram 7: Behavior Model of the Offer Management Component .......................................23

Diagram 8: IBM blueprint ......................................................................................................23

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Page 5 of 26

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

1

Background

1.1 The Opportunity – Cloud Enabling the Banking Industry

The Cloud is changing the way the World interacts at work and at play. The

enthusiastic adoption of mobile devices and the Internet in advanced economies has

spawned a frenzy of Cloud based application innovation and service developments.

This coupled with demand from emerging markets and even some third world

activities will combine to drive a huge global growth in computing and data needs

which are/will be serviced in many cases by Cloud. The promise of widely accessible,

low-entry-cost, scalable solutions with improved operational efficiency and flexibility

has attracted big and small business interests alike. Furthermore rapid development

approaches are enabling the assembly of far more agile and adaptive business

solutions. In some cases the development cycle is fast enough for developers to

adopt an iterative ‘trial and error’ approach.

Application stores and their associated Cloud services are rapidly changing social

behaviour. According to Gartner, the public Cloud services market was estimated to

have grown by 18.5% in 2013 to a total $131 billion worldwide, up from $111 billion in

2012. Meanwhile, IDC estimates that by 2020, nearly 40% of the information in the

digital universe will be in the Cloud in some capacity. So far much of the growth in

the Cloud has been driven by the take-up in social, consumer-centric applications. In

business perhaps the biggest driver has been cost savings with the consumption

based pricing model offered by the Cloud allowing businesses to avoid large capital

expenditures for technology infrastructure. Despite the obvious potential the impact

on mainstream commercial applications is modest in comparison and particularly so

in the Banking Industry.

There are many reasons commercial enterprises struggle to fully leverage the Cloud.

Perhaps the most obvious is their scale and complexity. It is one thing to provide a

stand-alone mobile phone-based application to help an individual find a place to eat,

manage their personal finances or exchange messages with their friends. But when

the application has to connect multiple users performing specific business roles that

are involved in a complex transaction that might be influenced by events in many

different locations, it becomes a far bigger technical challenge.

In order to support commercial applications in the Cloud additional design insights

are needed. One described in this paper provides a standard definition of the

functional ‘building blocks’ that everyone can use to assemble their commercial

applications. For some of the more commodity type of business activities such as

payments or financial accounting standard approaches are already emerging. But a

comprehensive definition of the full range of suitable building blocks covering all

commercial activity is not yet available. This paper explores how the BIAN Service

Landscape may be used to define just such a comprehensive commercial blueprint

for banking, a blueprint that could be used to ‘Cloud-enable’ the banking industry.

Page 6 of 26

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

1.2 Defining the ‘Cloud’

The term ‘Cloud’ has become ubiquitous referring to many different types of

computer based service. The overarching concept is of virtualization’ - providing

remote access to technology based capabilities over a network, typically but not

limited to the Internet. The range of virtualised capabilities bundled under the ‘Cloud’

banner covers most types of computer service including scalable IT infrastructure,

application development environments and integratable software applications.

This complex array of capabilities can be grouped under three broad categories:

IaaS – Infrastructure as a Service – addresses virtual access to processing

power, storage and other hardware. Examples of IaaS Cloud services include

Amazon Web Services (AWS), Rackspace, IBM’s SoftLayer and SAP HANA.

Though there can be latency in Cloud based access to IaaS, the key benefits

include easy access to low-cost-entry and ‘opex’ priced capabilities with

scalable and resilient technical infrastructures

PaaS – Platform as a Service – addresses virtual support for application

development and deployment. This can include different levels of application

development support but at a minimum provides application hosting and

deployment capabilities. Examples include AWS, Microsoft Azure, SAP HANA

and IBM BlueMix. As with IaaS the key benefits include low entry costs and

scalability plus access to leading practice application management capabilities

SaaS – Software as a Service – is the most conceptually complex and

perhaps least exploited aspect of the Cloud. It covers centrally delivered and

licensed software that can provide standalone or integrateable functionality.

This includes business productivity solutions such as Microsoft’s Office 365.

Business application examples include IBM’s Kenexa workforce and human

capital management solution, Salesforce’s CRM portfolio and Google Apps. Of

particular relevance for banks, BIAN member Temenos offers its end-to-end

banking application ‘T24’ in the Microsoft Cloud. SaaS is perhaps the aspect

of Cloud with the greatest potential for business model transformation, but it is

also the most challenging to integrate into a complex business enterprise.

In addition to the three broad categories of Cloud solutions, a distinction is often

made between the Public- and Private Cloud. This has many similarities with the

Internet/Intranet distinction in the past where a large enterprise might host its own

dedicated ‘Intranet’ typically for security reasons but also hoping to benefit from the

ease of access/flexibility of the Internet protocols. With the public Cloud the service is

publicly accessible and security is assured by various access controls. Enterprises

and indeed regulators have to concern themselves with the level of security and

assurance available with Public Cloud offerings, though the trend is towards evergreater acceptance as security improves. Where the security concerns justify, a

Private or Dedicated Cloud instance can be offered that limits participation to one or

a selection of enterprises. For simplicity the distinction between Public and Private

Cloud implementations (and the intermediate ‘Hybrid Cloud’) is not addressed further

in the remainder of this paper – the design approaches described can be used in

either configuration.

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Page 7 of 26

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

1.3 Layered Access to the ‘Cloud’ – the context for using BIAN

To explain the many considerations for adopting the Cloud but in particular to clarify

the possible role of the BIAN model it helps to build up the usage patterns in layers

corresponding to the three categories of Cloud solutions already described. Starting

at the base with infrastructure (IaaS). Software has long run in virtual machines (VM),

allowing applications to be moved between and share physical devices. VM

capabilities that were first developed to provide greater operational flexibility,

utilization and resilience can easily scale to exploit the virtualization opportunities

offered with the Cloud. The practice was established with Data Centers decades ago

and with the many technical and procedural advances since, IaaS now offers a

comprehensive array of capabilities that can transform the cost of technology use

and ownership. But IaaS only has a direct impact on the technical operations of a

business enabling it to be more efficient and flexible in the IT support it provides.

Building on virtual access to the technical infrastructure through IaaS, the next layer,

PaaS, provides a virtual application development and management environment.

With PaaS and its growing array of associated tools and techniques application

development can benefit from easier application utility re-use, rapid iterative

development approaches and streamlined application version management and

distribution. The impact as with IaaS and technology operations can be

transformational for the application development and administration functions. But

again any impact on the business itself is indirect, reducing application development

costs and improving application enhancement response times but not significantly

changing the nature of business execution itself.

Finally we come to SaaS – where the business applications are assembled from

Cloud enabled servicing capabilities. Some SaaS offerings are stand-alone in nature,

they provide virtual access to a service that provides a solution in its own right –

Office Software and consumer applications like Google, Twitter and Facebook are

good examples. Other SaaS offerings provide solutions that are intended to be

integrated into the overall business operations application portfolio – two notable

example already mentioned being Salesforce.com‘s CRM and the Temenos T24

Core Banking offering.

SaaS solutions, because they support business behaviors directly, promise

transformational changes to business practices. But to date the creation and

adoption of SaaS solutions has been limited to easily isolated business tasks or to

business activities where a common approach can be adopted with limited sitespecific configuration. How might a standard industry model that defines the full array

of generic business capabilities that could be delivered through Cloud based SaaS

help transform business behavior? That question is explored next.

Page 8 of 26

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

1.4 Business Model Transformation using the Cloud

With existing SaaS solutions a service subscriber typically integrates the ‘virtual’

service alongside their own in-house business applications. The relationship between

the SaaS service consumer and service provider in practice is little different from the

Cloud based delivery of infrastructure (IaaS) or platform capabilities (PaaS). In this

case, rather than accessing processing capabilities or a development environment

the requester is accessing some form of remotely packaged and executing

application logic. The business users within the calling enterprise may not even be

aware that some portion of their business applications are running remotely. As with

IaaS and PaaS the benefits relate to ease of set-up and access to leading practices,

there can also be operating efficiencies – but these may need to be partly offset by

unwanted marginal performance degradation from latency in the Cloud.

The BIAN model defines the complete array of all of the generic functional building

blocks that can be assembled to make any bank. These discrete business

capabilities could in theory each be offered using a Cloud based SaaS solution.

Using this construct as a common industry blueprint the possibilities open up

significantly. Instead of simply integrating selected virtual utilities within the internal

application portfolio, banks can now consider Cloud based outsourcing (and perhaps

in-sourcing) of whole aspects of their business operation to other banks, to nonbanks seeking integrated access to financial services and to specialised solution

providers.

There are already established examples of banks outsourcing operational elements

of their operation: it is common practice in high net-worth/private banking to

outsource much of the product execution and back office tasks to other banks; retail

banks outsource key elements of their consumer credit analysis to specialist third

party credit rating agencies. With a comprehensive banking model available in the

Cloud to structure the service exchanges for any aspect of banking what other

business arrangements are possible? When an industry model is used to package

Cloud based capabilities the role of the Cloud expands beyond virtualizing

operational capabilities to being a channel to form alliance partnerships where

potentially radical new collaborative business models can evolve.

In the next section the way the BIAN model provides an industry blueprint to support

this kind of in-source/out-source behavior is developed further. There is also a

discussion as to how the individual BIAN capability building blocks and the specific

and unique business role they each perform can be used to constrain access to the

services – this is an essential requirement to ensure operational security and integrity

is maintained as business activity is moved into the Cloud.

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Page 9 of 26

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

2 Cloud enablement using BIAN

This section provides a little more detail about how the BIAN standard is used to

define and organize Cloud-based services. A brief explanation of the BIAN approach

is provided here but it may help to reference the BIAN How-to Guide (available for

free download at BIAN.org) for a more complete description of the design concepts

underlying the BIAN standard

2.1 A new conceptual model to define the Cloud configuration

The primary use of the Cloud to date has been to provide virtual/remote access to

some hosted capability, technical or functional in nature. These hosted services often

exploit the scalability and flexibility of the distributed Cloud infrastructure to reduce

start-up costs, provide access to leading practice technologies and/or reduce

operational costs and complexity. In this conceptually centralised model each service

subscriber integrates their own dedicated instances of the Cloud hosted utility

services into their local business applications or working environment. The fact that

aspects of production are remotely supported may in cases be completely

transparent to their business users.

The approach described here that seeks to ‘Cloud-enable’ the Banking Industry

involves an extension to this centralised view of virtual service delivery. In an

extended model different banking industry participants and possibly non-bank

enterprises that need access to financial service capabilities offer and consume

business services from each other and specialist business service providers ‘through’

the Cloud. To represent this type of service exchange an additional higher level

‘conceptual model’ is needed to package and organize the Cloud services in a

standard form suitable for sharing between participants. This conceptual overlay is

defined using the BIAN Service Landscape and its constituent Service Domains. The

Service Domains define service enabled business capability partitions providing the

organizing structure for the SaaS solutions.

The BIAN Service Landscape and Service Domains are fully explained as noted

earlier in the BIAN How-to Guide. Some key properties are:

The BIAN model uses a very specific representation of business activity that

differs from most prevailing models: rather than modeling end to end business

processes that capture the linked sequence of actions needed to respond to a

business event, the BIAN model identifies the discrete business capabilities

that are involved in the event, without prescribing when or in what sequence

they may be engaged

Business applications developed from conventional process-based designs

tend to automate well-defined/repetitive activities, like a factory production

line. The BIAN designs can be used to architect applications that act as

loosely coupled, asynchronous service centers that interact through queue

based message exchanges, a design well suited to Cloud implementation

The BIAN Service Landscape contains the complete collection of business

capabilities that might make up any type of bank or banking enterprise – these

business capabilities are called BIAN Service Domains

Page 10 of 26

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

The scope of a BIAN Service Domain is designed to represent a discrete and

elemental business capability – the business role of a Service Domain is

canonical, meaning it can be consistently interpreted in any deployment

The business capabilities defined by BIAN Service Domains can be

implemented with an ‘encapsulating’ service boundary that allows them to be

in or out-sourced through the Cloud as long as all of their service

dependencies can be supported

The BIAN Service Domain establishes the scope and external service

boundary for a business capability without defining how it may perform that

role internally. The business purpose or role of a Service Domain – ‘what it

does’ - is highly stable over time even though its internal mechanisms – ‘how it

does it’ - will inevitably evolve as new techniques and practices are developed.

Because the BIAN Service Landscape and its constituent Service Domains have the

above properties, a banking business blueprint defined using BIAN Service Domains

is canonical/common for all banking activity. Also, because the service boundaries of

Service Domains are highly enduring the model is highly stable over time. As the

Service Domains encapsulate their internal working behind their service boundary,

systems solutions that are aligned to this model can use highly distributed serviceenabled environments, such as the Cloud to support a fully componentised and

distributed business operating model.

The diagram below shows banks as an assembly of (#9) discrete Service Domains –

note that the views are greatly simplified, in practice a typical full-service bank will

contain well over 250 different Service Domains and depending on its organizational

structure some of these Service Domains will have many duplicated instances. On

the left the diagram shows a conventional centralised Cloud service implementation –

the Cloud based service offers a virtual utility where each dedicated instance

accessed by a bank is integrated with its locally operated systems. On the right the

standard industry Service Domain blueprint is now used to connect a service provider

with two banks as well as allowing those banks to source services with each other

and a third bank, showing how the Cloud now can act as an operational service

broker for in/outsourcing services between banks (and non-banks requiring financial

service capabilities – example not shown) and service providers.

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Page 11 of 26

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

Diagram 1: Simple Cloud central utility service, brokered to multiple bank subscribers

As noted the simplified diagram shows the conceptual design for a shared service

model where the Cloud plays the role of a channel connecting participants in the

marketplace. Two points of clarification:

1. The BIAN Service Landscape currently contains some 280+ Service Domains

covering a broad array of business activities – the range of operational models

covering in/out sourcing combinations between banks, non-bank enterprises

and specialist service providers that could be supported is extensive. As the

approach is embryonic we do not attempt to explore or anticipate what these

many business model options may be in this paper

2. The model shows high-level conceptual roles, the Cloud is shown hosting the

utility service in one configuration and simply acting as a channel in the other.

In implementation it is quite possible that the service provider in the second

‘brokered’ model may also choose to host their service delivery capability ‘in

the Cloud’ – the conceptual model on the right simply establishes the logical

configuration or execution responsibilities. In implementation the flexibility of

the Cloud to host services on behalf of parties can of course be used to

support any suitable physical combination of local and virtualized execution.

Page 12 of 26

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

2.2 Using Service Domains to Organize Cloud Services

In this section we discuss various considerations for using the BIAN Service

Domains’ semantic service operations to define SaaS specifications suited to Cloud

based implementation. The first point cautions that the exchanges described in the

BIAN model may include aspects that can’t always be readily supported in the Cloud

BIAN Service Operations can include exchanges not suited to Cloud Services

The semantic service operations that BIAN defines for its Service Domains describe

the service dependencies and interactions between Service Domains in high-level

semantic/conceptual terms – it is this collection of services offered and consumed by

a Service Domain that can be used to specify the SaaS solution elements. The

semantic service operations defined by BIAN typically involve the exchange of

business information that is clearly well suited to the Cloud.

Some service operations may include the associated movement of physical goods

and/or assignment of resources. Furthermore a BIAN service exchange may be

sensibly implemented using a simple one-way message based delivery of structured

information/data or may require a far more complex iterative dialogue possibly

including highly unstructured information. A BIAN Service exchange may also

request the execution of some kind of activity on the part of the called Service

Domain for which there may be a result or response anticipated at some point in the

future.

These different service exchange properties need to be accommodated in any SaaS

Cloud based solution. In practice there may be some BIAN service operation

dependencies defined in the BIAN standard that are not suited to a Cloud SaaS

implementation because there are aspects of the service exchange that cannot be

easily supported – if there is a physical exchange of cash for example. There may

also be performance and security limitations that constrain the use of Cloud based

solutions in situations. These issues need to be considered on a case-by-case basis

but it is assumed that the significant majority of BIAN service interactions are suited

to a Cloud implementation.

BIAN Service Operations as a Canonical Service Directory

In theory the core systems for a bank could be architected as a collection of

networked standalone service centers each aligned to the specific business role

corresponding to a BIAN Service Domain. In practice however, most banks operate

monolithic transaction processing systems that combine the roles of multiple Service

Domains on larger integrated systems. In order to present the more flexible service

center structure for business application assembly, banks are increasingly using

technology such as an enterprise service bus (ESB) to structure and package access

to these monolithic host systems.

BIAN Service Domains each define a discrete, non-overlapping business capability

and the service operations they offer similarly define unique non-overlapping

business services. As a result the complete collection of Service Domains and their

service operations can be used to define a comprehensive, canonical business

service directory with discrete/non-overlapping services for the ESB.

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Page 13 of 26

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

These services can then be mapped to the monolithic hosts systems ‘behind the

scenes’ using various technical approaches to optimise legacy host access.

The canonical ESB service model defines a stable target state that legacy

rationalization can work towards incrementally by mapping the legacy host systems

to selected sub-sets of the BIAN defined business services. The ESB then offers

access to well-structured business services for application assembly, masking the

complexity of the underlying host systems. The ESB based host wrapping approach

is shown schematically in the diagram:

Diagram 2: BIAN service domains & service operations as an enterprise service bus

directory

More details about using the BIAN standard to configure ESB based host service

access can be found in the BIAN How-to Guide. It is a rapidly evolving use of the

BIAN model that shows significant potential, in particular much is being learned about

the benefits and practicalities of wrapping overlapping legacy host systems behind

the ESB. These host access approaches include host session sharing, data caching,

master/slave data custody role resolution. This host access layer can be very

complex, particularly when the host environment includes overlapping legacy

applications.

Page 14 of 26

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

The mapping of the host-based information to the BIAN semantic services is shown

in the following diagram:

Diagram 3: BIAN servics Mapped to host data structures

For the purposes of this discussion on Cloud it is only necessary to consider the

application assembly side of the ESB equation, where business applications are

assembled using the ESB Service Domain aligned service operations as shown in

the earlier Diagram 2.

Constrained Access to Service Operations – Service Domains Provide Context

The business services that may be enabled using a mechanism such as an ESB are

suited for the controlled access between applications developed within the confines

of an enterprise. When the services offered by one Service Domain are consumed by

another Service Domain within the same enterprise arrangements can be put in

place in advance to ensure that the service call is legitimate and the requested action

is appropriate for both the requester and the called Service Domains. When services

are made available through the Cloud these intrinsic controls can no longer be

guaranteed. Additional constraints are needed for the ESB offered service to ensure

its external use is appropriate.

When considering these necessary constraints it is important to remember that a

property of good service design is that the same offered service may be used by

many different callers in different but valid business situations transparently to the

service provider.

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Page 15 of 26

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

A simple summary of the obligations on the provider and consumer of a service is as

follows:

For the Service Provider – it must specify the service in sufficient detail for the

requester to determine whether the service is appropriate for their specific use

and then undertake to provide the service to that specification

For the Service Consumer (requester) – it must access the provided service in

a manner that is consistent with its intended use.

For example the Service Domain that provides customer reference details may offer

a ‘customer ID query’ service that is intended to help the caller narrow in on a

particular customer’s identity using available details of a subject perhaps to check

whether they are already known to the bank. The offered service will define different

properties that it can use to isolate a customer and the requester will provide values

to those properties to drive the query. Depending on the specificity of the values

provided the service might match many candidate customers. The obligation on the

service provider is to provide sufficient properties to the query for a close match to be

likely. The obligation on the requester is that they provide sufficient properties values

for the query to be targeted, hopefully eventually matching the single subject.

An example of unintended use or abuse of the service would be a call with very few

parameters defined so that the service is forced to return in the whole customer

directory as a result. This is an extreme example, but it shows that in addition to the

offered service specification there needs to be some contextual constraint that limits

the situations within which the requester employs the service.

One way to do this is to use the business role of a Service Domain as the

constraining mechanism for limiting access to offered services (and potentially for

filtering responses). In the example of the customer ID query the calling party would

need to initiate the request from some valid source, such as the Service Domain

handling Customer Relationship Management. This role would then be used to

constrain the scope of the query, perhaps to include only customers already

assigned to the relationship manager and then only providing access to customer

details that are relevant to relationship management.

All services offered through the Cloud would only be available to requesters that

manifest themselves as valid Service Domains. In order to provide this constrained

access the service provider would either need to certify that the calling party is acting

as a Service Domain or more likely the service provider will publish Service Domain

software ‘containers’ to the Cloud that act as ‘proxy’ Service Domains. Requesters

would then build their applications within these containers in order to have structured

access to the services that they are enabled to call and the input that they may offer

back.

The published proxy version of a Service Domain may of course impose further

constraints to the internal equivalent Service Domain to provide additional controls

needed for external access. For example the external proxy for Relationship

Management may not have access to the full range of customer reference

information that the internal Relationship Management function has.

Page 16 of 26

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

This ‘proxy’ Service Domain Cloud access approach is shown the diagram

Diagram 4: BIAN serviecs constrain access, creating an application container

Finally to complete this section there are a couple of points of clarification with

respect to the design and specification of Cloud services:

Notable Design Properties for Cloud Services – defensive service calls

Due to the loose coupled and distributed nature of Cloud based service exchanges

all service access needs to be ‘defensive’. For the service provider this means that

they need to constrain service access and filter requests to ensure that the calls are

legitimate and appropriate – the use of Service Domain ‘proxies’ just described is one

way to do this. There are many other practical/technical considerations, such as the

use of access authorization ‘tokens’, managing service volumes and performance

that are not addressed in this paper.

For the service subscriber the access also needs to be defensive, meaning that the

requester needs to deal with delayed, missing and erroneous responses.

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Page 17 of 26

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

Notable Design Properties for Cloud Services – required information precision

The requester/consumer also needs to ensure that the meaning of the information

exchanged is agreed to the required level of detail with the provider. For some

service exchanges the terms may only need to be agreed at a fairly vague semantic

level. For a marketing service to return a list of prospects to a sales function both

parties can loosely agree the term ‘prospect’ quite safely. How both involved parties

may choose to define and fully represent the concept of a prospect internally can

differ significantly without compromising the effectiveness of the service exchange.

Conversely when a credit assessment function requests the details of account

activity and balances, the agreement as to the required data content and its meaning

clearly needs to be defined with far greater precision for the many financial

transaction details and derived values contained in any statement that is returned.

The correct semantic definition of the information exchanged using Cloud services

needs to be appropriate for the intended use and as the above examples show, this

will vary for different services. Meta-data definitions of the semantic service content

can be defined and used to ensure the consistent interpretation of the service

contract where higher levels of data precision are needed. The fairly technical topic

of traceability between the semantic BIAN designs and the underlying

implementation messages is the topic of a separate paper that can be referenced on

BIAN.org.

Page 18 of 26

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

3 An Example using BIAN to Specify Cloud SaaS

In this section we describe how the BIAN Service Domains and their semantic

services are interpreted for implementation in the Cloud using the example of

account opening. We start by pointing out that in addition to the obvious technical

differences, the business context for providing service-based access is fundamentally

different in the Cloud to the more traditional ‘dedicated’ customer channels.

In the past a customer would head to the local bank branch to apply for a mortgage,

something they can now do easily from their mobile phone. But they can use that

same mobile phone to arrange their gym membership or order dinner - the bank must

establish its own differentiated virtual presence in the new environment in the same

way that having high street bank branches established a local presence for banks in

the past. The need to differentiate in the new mobile channel space is made more

pressing as the Cloud is an open environment where other non-bank enterprises may

now offer many competing services for which Banks have been the only source in the

past.

The new customer access environments provide both an opportunity and a

significant threat for Banks. They can now support far better product matching and

ease of access to a wider range of bank products and services that can be woven

more tightly into customer behaviors, but they also introduce greater competition as

other banks and non-banks enjoy similarly open access to the customer. Agility and

innovation will be key to success.

The BIAN model, by breaking activity into discrete generic elements, can provide key

insights into this aspect of the customer interaction. An example of the customer

account opening activity shows how past practices where the process is closely tied

to the specific product or service on offer can now be opened up to allow the process

to be driven by greater customer insights and to include different product

combinations.

3.1 Example - account opening

As noted, the account opening process has traditionally been used by a bank to

establish a relationship with a customer in the context of the customer buying specific

products and services. In the conventional product-centric approach, account

opening has been a function supported by the core banking application with each

account opening procedure supporting its own specific product type. But as banks

move to being a customer-centric enterprise, account opening becomes a key

customer-facing business process that enables banks to establish a relationship with

the customer spanning the product silos.

A bank may even “open an account” for a customer where some of the products

involved may actually be managed by business partners. Thus the need to decouple

the account opening function from the “product processors” (the essence of core

banking applications) becomes evident. Universal account opening becomes a

collaboration among a set of business capabilities with the goal of establishing and

enhancing a relationship with the customer as well as setting up the product delivery.

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Page 19 of 26

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

Not surprisingly, this is a manifestation of business activity particularly well suited to

the BIAN representation and a Cloud based implementation.

Below is a list key requirement of universal account opening:

Flexibility: The activities involved and their sequencing could vary between

instances of account opening process as this depends on the products

involved, the customer profile, and the specific terms & conditions

negotiated.

Multi-product support: One or more products could be involved and any of

the products the bank sell could be included.

Dynamic bundling support: The bank should be able to dynamically

assemble a bundle of products and services and negotiate the terms &

conditions at the bundle level based on customer insight and product

profitability data.

Relationship pricing: The bank should be able to dynamically price the

offerings based on the customer relationship with the bank and other

factors.

Next best action: The bank should be able to use the account opening

process to cross-sell/up-sell as it provides a great opportunity to engage

the customers on their financial needs.

Integration with partner applications: as mentioned earlier, its partners may

service some of the products a bank sells, so account opening should

facilitate integration with partner systems through APIs. Another example is

to kick off the account opening process from third party applications such

as an e-commerce app on a mobile device.

Integration with enterprise applications, primarily applications that manage

systems of records.

Integration with external services: As Cloud-based business services

become available, banks are rethinking their IT strategy leading to

componentization of monolithic applications. This applies to account

opening as well as many of the participating services will be sources from

Cloud-based service providers.

These complex requirements can be effectively modelled using the array of BIAN

Service Domains that support the many aspects of the customer interaction. The

Service Domains define the different discrete elements involved in a way that covers

the range of customer related perspectives and activities while also ensuring that

they are decoupled from the products and services that may be ‘matched’.

3.2 Solution Design – a simplified example

The BIAN Service Domains used to model the account opening example above

define a business architecture that can be mapped to an underlying systems

architecture for implementation. In practice there are times when a BIAN Service

Domain can be supported by several finer grained IT components and a larger IT

system may support several Service Domains. These specific Systems Architecture

mapping variations are discussed in the BIAN How-to Guide. For the purposes of this

paper it is easiest to consider the most common situation where a BIAN Service

Domain maps directly to a single IT Service Component.

Page 20 of 26

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

In this case there is a simple correspondence between the scope of the Service

Domain and its semantic service operations and the IT Service Component and its

service/message boundary. Each IT Service Component provides a set of APIs that

enable clients to invoke the services provided by the corresponding service domain.

The implementation level detail of the API’s will typically be far more detailed than the

high level semantic service descriptions, but their collective scope/purpose will be the

same.

In more technical detail – an implementation approach (using IBM’s BlueMix)

In order to explain implementation in slightly more detail by means of a worked

example, here we briefly describe how the BIAN Service Domain designs could be

implemented in IBM’s BlueMix Cloud development environment. The IT service

components store the ‘state’ of the control object instances associated with the

corresponding service domain. Behavior of these components – that is, their

response to a service request – is determined by a set of configurable business

rules. These rules take into account the state of the control object, the service being

invoked, and the parameters being passed.

The first step in the solution design is to identify the Service Domains that participate

in the collaboration. These domains are partitioned into two groups:

Service domains that are external to the enterprise and provided as shared services

on a public Cloud

Service domains that are internal to the enterprise and provided as shared services

on a Private Cloud.

Below we show the main BIAN Service Domains that support for account:

Diagram 5: Service Domains involved in the offer process

For this discussion, it is assumed that the components Customer Credit Rating,

Correspondence, & Sales Product are in group 1 (external/out-sourced) while Cross

Channel, Offer Management, Customer Relationship Management, Party Data

Management, Position Keeping, Product Matching, & Current Account are in group 2

(internal).

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Page 21 of 26

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

Next, detailed designs for each component are developed. This includes API

definitions, design of the local storage, and the business logic that drives the

component behaviour. As an example, below we give the design of the Offer

Management component.

Offer Management Component Design

The granularity of a BIAN component is defined around the life cycle of the control

record it is associated with. For the Offer Management component, the control record

is the ‘offer’ that the bank is making to a customer to sell one or more of its products.

The design of the component should address (1) how interfaces are defined to

expose services offered by the component (2) how component behavior is defined

that leads to the implementation of these services, and (3) how data associated with

the component is managed. For the Offer Management component, interfaces are

defined using REST APIs, behavior is defined using a Finite State Machine, and the

data is managed using a relational database. Figure below shows the component

structure.

Diagram 6: Offer Management Component Structure

REST APIs and the corresponding BIAN service operations are shown in the table

below:

REST API

BIAN

Service

Operation

Description

HTTP POST /offerdatamanagement/offer/{offer-data}

Create Offer

HTTP GET /offerdatamanagement/offer/{customeridentifier}

N/A

HTTP GET /offerdatamanagement/offer/{offeridentifier}

N/A

HTTP POST

/offerdatamanagement/offer/update/{offeridentifier}{updatedata}

N/A

Creates a new

offer

Retrieves offers

for a given

customer

Retrieves a

specific offer

Update an

existing offer

Page 22 of 26

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

The behavior of the Offer Management component is captured in a finite state

machine, as shown below.

Diagram 7: Behavior Model of the Offer Management Component

The data owned by the control object, in this case the offer, is managed by the

component using a relational database. The data elements for offer management

include: {Offer Identifier, Offer Start Date, Offer End Date, Product Identifier(s) - one or more

products, Customer Identifier(s) - one or more customers , Offer Description, Offer Name, Offer

Approval Date, Offer Lifecycle Status, Offer Purpose, Offer Term Type, Offer Channel(s), Offer

Documentation (agreement terms and conditions), Offer Conditions, Offer Source of Income, Offer

Collaterals The collaterals against which the offer if provided , Offer Currency Type,..}

This specification could then be implemented using an IBM blueprint as shown

schematically below.

Diagram 8: IBM blueprint

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Page 23 of 26

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

3.3 Future Development Needs & Opportunities

The rapid changes in the customer access channels brought about by the Cloud and

other technological advances are driving changes in regulatory perceptions and

requirements and fuelling competitive activities that promise to reshape the banking

landscape. Some highlights underscore the pressing need for banks to prepare for

and align to these changes:

Regulatory changes – in addition to the obvious move to increase the range

and complexity of regulatory controls, regulatory changes are also influencing

the nature of the services that can be offered. For example a recent European

directive requires that banks be able to support a customer’s request to

execute payments through any payment service

API based bank access – many banks are exploring different ways to

support application based access to their host systems, activities that may

benefit from the approaches outlined in this paper

App stores developed by 3rd parties – an extension to banks providing API’s

for their customers to access their systems is providing APIs for third parties to

develop new applications and services that integrate the banks capabilities as

some element of their service offering

Different paths to capital – in addition to financial service innovations,

community based funding models are constantly evolving that may offer

alternative cash flow, investment and risk management options for businesses

Service specialists – Credit Agencies are a good example of a specialist

service that has been outsourced by many banks, with the scope and flexibility

of the new Cloud technologies, what other specialist services may appear?

Page 24 of 26

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

4 Summary

The BIAN model is unique in that it defines discrete elemental and canonical service

centres that collectively cover all banking activity. Packaging Cloud based SaaS

offerings to align to the logical partitions of the BIAN standard provides a common

industry blueprint for shareable business services. Banks, their alliance partners and

customers can collaborate by building integrated applications in the Cloud that span

their different operations. Furthermore the Service Domain role definitions can be

used to define and implement service access constraints needed to ensure legitimate

and appropriate use of Cloud based services.

This is a more advanced use of the Cloud than existing stand-alone services and

application ‘service utilities’’ that developers can integrate within their local

application portfolios. It is a business capability driven model that supports alliance

based partnerships and business application integration that exploits the open,

connective nature of the Cloud to bring in new players, support new collaborative

business models and expand the markets for the banks.

Financial services firms arguably have been more cautious than other industries

about adopting Cloud services, with well-placed fears about data security and

regulatory concerns top of mind. But as well as being a source of competitive threat it

is becoming increasingly clear that the Cloud offers many potential advantages for

banks.

Future patterns can be seen in one area where the Cloud is already playing a

significant role – Payments. Banks may not be fully aware that they may today be

indirectly involved in aspects of payments and card fulfilment that are already Cloud

resident. The proliferation of new and innovative payment mechanisms using the

Cloud demonstrates how traditional approaches can be transformed and established

banking relationships threatened.

Though the role for banks as the final account holder is probably not under

immediate threat from changes in payments, banks must be careful to ensure that

their customer relationships and the associated insights they can gain are not

undermined as more flexible payment options are presented to their customers by

competitors. More importantly these Cloud related changes are likely to apply

increasingly across many other banking activities not just to payments.

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

Page 25 of 26

Cloud enabling the Banking Industry

5 Conclusion

It is early days in the development and adoption of the BIAN banking standard. But

the BIAN model appears to enable unique insights into Cloud related business

behaviors by providing an industry blueprint matching the business operations to the

underlying systems. The Cloud based solutions can operate as a loose-coupled

network, allowing banks to form alliances with other banks, specialist service

partners and even to integrate their services within their customer’s operations.

The conventional product and service boundary that banks have with their customer

blurs as banks can offer more flexible operational access to their core capabilities

such as: cash flow management, currency exchange and cash management,

financial risk management, financing and access to primary and secondary

investment exchanges. Banks need to master the different model views such as that

of BIAN to be able to position themselves for the fundamental changes already

underway in the banking industry that are fuelled by the Cloud and other related

technology advances.

Page 26 of 26

© 2014 BIAN e.V. | P.O. Box 16 02 55 | 60065 Frankfurt am Main | Germany

© Copyright 2026