WELCOME DOLLHOUSE to the Gloria Vanderbilt

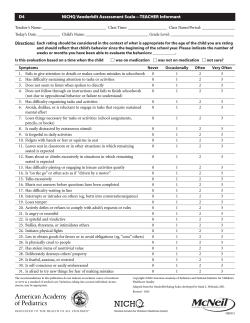

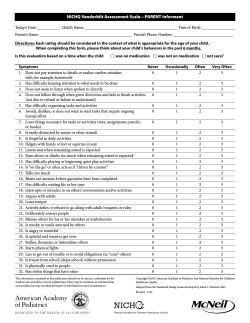

WELCOME to the DOLLHOUSE Inside her private art studio, Gloria Vanderbilt fashions a teeming universe—of paintings and objects that, like their creator, are dreamy, provocative, and full of inner strength. The artist invited T&C to take a rare look at the working life of an American icon. I By M I C H A E L L I N D S AY - H O G G ’ D B RO U G H T A PA D A N D P E N with me when I visited her in her studio. She was wearing a light blue painter’s smock over black slacks and a black sweater, with Chinese slippers on her feet. The smock had some dabs of paint on it. She was wearing no makeup, and, although some years past her first youth, she looked as pretty as the serious girl who might have sung in the school choir, with intelligence as present in her face as softness and clarity. The reason I’d brought a pad and pen was to take notes as I talked to Gloria about her painting. But after a few scribbles—“Wheeler School in Providence,” “Art Students League, charcoal drawings from live models”—I gave up, because I realized that wouldn’t really get the job done. After all, I’ve known her for 55 years, since I was a 16-year-old (when my mother introduced me to Gloria and her husband, Sidney Lumet), and then in many different, and delightful, ways, as our paths connected and crisscrossed throughout the years. Vanderbilt: a name signifying great wealth. Gloria: signifying celebrity, at first of an unwelcome kind, when she was the subject of a tabloid sensation custody case at age 10, and then for her fabled beauty, marriages, and romances. But if that’s the only way you think of Gloria Vanderbilt, you’ve got her dead wrong. When I look at her work, my friendship with her is out of the equation, and my eye is always objective: She is a great and original artist and painter. Over time Gloria’s work has gone in many different directions, has sustained, and continues to surprise. She works in different media (oil, acrylic, egg tempera), and her palette has always been bright with varieties of pink, red, lavender, yellow. It is vibrant, vivid, but has only been in the service of an idea, a composition, a feeling, an emotion, and is never after just prettiness. And in her work there is nothing of sentimentality, even when the subject is tender: a contented couple with two children in the background, or a mother with a child, or a woman in a hat. They and hundreds more have a kind of power to them, with a sense not of melancholy but of what the passage of time means, of how the present will one day be a memory. If Gloria were a dilettante, seeing her work would be like looking into a kaleidoscope, with the loose bits of colored glass arranging themselves in predictably changing, pretty, and boring combinations. But in her hands, old and expected patterns can be wrenched, and any prettiness will have a sense of torque to it and even, maybe, a frisson of something violent. Photographs by J O N AT H A N B E C K E R 64 | T OW N & C O U N T R Y THE GLORIA OF IT ALL Gloria Vanderbilt, in her own Fortuny dress, relaxes in her Manhattan apartment. The portrait at right is of her mother, Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt. Opposite: Vanderbilt’s Doll House, a work in progress. Styled by Jade Hobson THE REFLECTIVE LIFE Vanderbilt painted Father and Son: Wyatt and Carter Cooper in 1965. Opposite, from top: The artist created a hall of mirrors in her apartment— an appropriate effect for a woman of myriad parts; a silk dressing gown hangs on a closet door in Vanderbilt’s bedroom, next to Pictures on a Bedroom Wall, 1975. In some early works of Cézanne, before he’d rearranged apples and Mont Sainte-Victoire, the paint was laid on thick and rough, the brushstrokes harsh, and the scenes were of violation, sexual and emotional—the figures twisted, very untranquil, reaching, grabbing, with one character wishing not to be denied, the other wishing to flee. In some of Gloria’s work, although her paint is more delicately applied, many of these elements are also present. One of her paintings is of a little girl (herself?) witnessing the death of an adult (her grandmother?) in a bed. The child—in white, on a dark green background, shot, like silk, with black—is stabbing an arm out, as if wishing for something to stop, to be other: “No, don’t go!” And in the upper center is an extraordinary figure in turmoil under the sheets, seeming to be in the throes of a passion—a passion to hold on, not to surrender, a character in a frenzy you could read as erotic if you didn’t know the issue at hand. The working title was Deathbed Scene, which Gloria changed to the more open-ended Transition. But you still know that there is a kind of violence to what is going on, whether mortal or sexual. (I’ve often read, and found, that there is a connection between the two.) Like any great artist, Gloria is both innocent, in that she can always be surprised, and sophisticated, so that she understands the inescapable hazards of interpretation—which is something central to being alive: “Is this what is going on, or is it that?” I said to Gloria that some of her work seemed masculine. By that I meant it has what are thought of as qualities associated with manliness: boldness, something direct and muscular, if of a sinewy kind. From the mouth of this most feminine of people came a little laugh, half mirth and half scoff, and she said, “Oh, darling, I think women can do bold and direct too. Don’t you?” We smiled at each other. Her point was made. In her hands, any prettiness will have a sense of torque to it and even, maybe, a frisson of something violent. F R A N C I S B AC O N WA S A F R I E N D O F M I N E , A N D M O R E than once I went to visit him in his studio in London. It was a jumble, a mess, with paint flung off many brushes onto walls already thickly impastoed with many earlier signs of frustration. Ankle deep it was, with rags, newspapers, photographs, squeezed-dry tubes of paint, and mutilated, rejected canvases. And great works of art, on their way. In contrast, Gloria’s studio in the East 50s is pristine, almost nunlike. Everything is in its place—some paints on the table beside her easel, others neatly arranged on a shelf. In a small adjoining room she works on her Dream Boxes, with the mélange of things she needs to create them at hand. It was in this modest studio that she was forced to live for two years after she was swindled by her psychiatrist, the inaptly named Christ L. Zois, and her lawyer, Thomas A. Andrews. The latter was disbarred in 1992 and died soon afterward, just before a judge ordered his estate to pay $1.4 million to Gloria. Zois was ordered to pay a judgment of $97,300. (He lost his license to practice in New York in 1995 but still lives in a manner that could be described as extremely comfortable.) Made broke by the affair—and receiving, she says, not a penny of the judgment—Gloria sold her much-loved family house in Southampton and her apartment in New York City. So she lived here, survived, and went on painting, until fortune smiled on her again. She now lives in an apartment in the same building as her studio, full of her paintings, objects, mementos, a lifetime of things, monitored by an intelligence and sense of proportion, and a mind full of curiosity. One of the funny things about art is that where you see it affects your perception. If it’s in MoMA, or at the Whitney, or in a Gagosian gallery, you think this might be something valuable, in both senses. Larry Gagosian has become such an influential and powerful dealer that you can imagine a potential buyer asking, “A million dollars for that? GETAWAY CLAUSE “Crime Does Pay—But Not Very Much” is the subtitle of a new study on the economics of bank robbery. It concludes that the average stooge nets around $20,000 per heist and will be arrested within 18 months. Both numbers increase substantially when the banks’ executives are factored in. JA N UA R Y 2 0 1 3 | 67 WO M A N ’ S WO R K Vanderbilt’s Transition (2006). Opposite: Vanderbilt with her Mother and Child with Balloons (1956) and Pink (1965). JA N UA R Y 2 0 1 3 | 69 INNER VISIONS The carved head placed atop a stack of books that Vanderbilt covered is a found object. The photograph is of her half-sister Cathleen Vanderbilt de Arostegui, taken by Nickolas Muray. Opposite, clockwise from top left: Details from four of Vanderbilt’s otherworldly Dream Boxes: New Year’s Eve (2001), Yes (2008), Forever After (2001), and Destiny (2010). 70 | T OW N & C O U N T R Y Is it worth it?” and a shaven-headed, nattily dressed gallery operative blinking behind his Morgenthal Frederics round glasses, answering, “Sure it is. It’s a Gagosian,” as if the place it’s seen is as important as the artist. For her part, Gloria sells some paintings, but others she holds on to. “Gloria continues to paint fiercely and passionately,” Christopher J. Madkour, the executive director of the Huntsville Museum of Art, in Alabama, and a longtime supporter of Gloria’s work, told me. “There are some works that are so emotionally connected to her that they will never be sold or leave her studio. They are her family, and like a mother she protects them with all her heart—which is very big.” Even so, Gloria has been the focus of one-woman shows since 1952 (including an influential one at the Hammer Galleries in 1969), and Madkour mounted exhibitions of her work when he was directing the Southern Vermont Arts Center, in Manchester, including a sell-out 2007 show that featured 30 of Gloria’s paintings. She maintains an online gallery at gloriavanderbiltfineart.com and had a huge retrospective last fall at the New York Design Center. Still, I do not think enough of her work—with its gloves-off uniqueness—has been seen. When Gloria paints, what I imagine is that there is an empty canvas, with tubes of paint carefully laid out on the table beside her, and a selection of brushes. And then she starts. There’s an image in her head that she wants to construct and explain. Or perhaps there’s nothing yet except the impulse to put her brush into a color on her palette and paint a stroke of red or a black line, which may turn into the sense of a face, and the idea will come from the brush. She knows there will always be something, and it doesn’t matter what track it comes in on. And the paint will be the idea, and she’ll be led by the paint and then lead it, like a dance in which one will know the steps and the other will follow, and then they’ll switch, masculine and feminine trading, then combining into one entity. I’ve never seen her paint. It’s an intimacy JA N UA R Y 2 0 1 3 | 71 I’d like, but only if she didn’t know I was there. Painting, of course, is something you usually want to do alone, because you are more revealed in the doing than when it’s finished. I paint myself and know the concentration involved, trying to free the great engine of imagination and then harness it, before it gets away from you, or, if you’re feeling particularly strong, letting it and ending up somewhere you never dreamed of. Which takes us back to the Dream Boxes— objects Gloria has been making for years. In a Plexiglas box with a sliding panel (in case she ever wants to change something), there will usually be a doll—or a plaster head, with memento mori—on the floor of the box, and, attached to the sides, dice, a smaller doll, string, dried flowers, or other objects. “Don’t you think dolls are sort of creepy?” I asked her. “Oh, of course. That’s part of the point.” “Where do you get the dolls, the things?” “In thrift shops, wherever I can find them.” I asked her if she painted or made objects when 72 | T OW N & C O U N T R Y she entered into a relationship. She paused for a good long moment. I wondered if she’d heard me. She had. She was thinking of what has been important to her. “When I start a love affair, I just sort of throw myself into it. No, I don’t paint then.” I remembered that to be the case from when we were together. I drank Negronis then and she did too, taking pleasure in the mixture of gin, Campari, and red vermouth. With a head full of memory and experience, and with a kind of sensitivity that is alert to the highest or deepest notes of human connection, there is still something very uncluttered about Gloria Vanderbilt. And whatever she has gained from the Vanderbilt name and from beauty, she has been knocked around and suffered because of them as well. It shows in her work, which should go more into the world, be seen by more, be released, like her own pure heart. After one Christmas, a holiday that has bad memories for her, I’d telephoned and asked what she’d done. “I painted all day and had a peanut butter and jelly sandwich for lunch.” • L A DY ’ S CHAMBER Faraway, painted by Vanderbilt in 1972 as part of a triptych, is named for her former Connecticut house, which is depicted in the background; the figures crossing the Mianus River are her husband Wyatt Cooper and her sons Christopher and Stan Stokowski, with the artist herself leading the way. Opposite: The headboard is embellished with a Russian icon, and the large work to the left is the artist’s 1968 Celebration. Hair by Akira for Kenneth Salon. Makeup by Miriam Boland. “Don’t you think dolls are sort of creepy?” I asked her. “Oh, of course,” she said. “That’s part of the point.” M O N T H T K 2 0 1 2 | 73

© Copyright 2026