Association between diabetes and depression: Sex

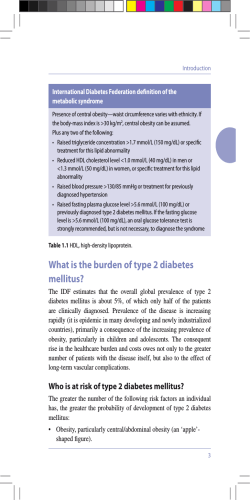

ARTICLE IN PRESS Public Health (2006) 120, 696–704 www.elsevierhealth.com/journals/pubh ORIGINAL RESEARCH Association between diabetes and depression: Sex and age differences W. Zhaoa,, Y. Chena, M. Lina, R.J. Sigalb a Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine, University of Ottawa, 451 Smyth Road, Ottawa, ON, Canada, K1 H 8M5 b Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Canada Received 17 March 2005; received in revised form 4 February 2006; accepted 5 April 2006 Available online 7 July 2006 KEYWORDS Depression; Diabetes; Cross-sectional study; Age factor; Prevalence; Health survey Summary Objective: To examine the association between diabetes and the prevalence of depression in different sex and age groups by analysing the crosssectional data from the National Population Health Survey, conducted in Canada in 1996–1997. Study design: A total of 53 072 people aged 20–64 years were included in the analysis. Depression was defined as depression scale X5, based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (CIDI-SF). Respondents who answered the following question affirmatively were considered to have diabetes: ‘do you have diabetes diagnosed by a health professional?’ Methods: A multiple logistic regression model was used to adjust for potential confounding effects, and a bootstrap procedure was used to take sampling weights and design effects into account. Results: The prevalence of diabetes was much higher in people aged 40–64 years than in people aged 20–39 years (men: 4.7% vs. 0.5%; women: 3.5% vs. 0.8%, respectively). In contrast, people aged 20–39 years had a slightly higher prevalence of depression than those aged 40–64 years (men: 3.1% vs. 2.9%; women: 6.6% vs. 5.4%, respectively). Diabetes was significantly associated with depression in women aged 20–39 years (odds ratio [OR] ¼ 2.52, 95% confidence interval [CI] ¼ 1.19, 5.32), but not in women aged 40–64 years (OR ¼ 1.62, and 95% CI ¼ 0.65, 4.06). The association was not significant in both age groups in men, but it tended to be stronger in the younger age group. Conclusions: The data suggest that diabetes is significantly associated with depression, particularly in young adults. & 2006 The Royal Institute of Public Health. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 613 694 6904; fax: +1 613 241 8120. E-mail address: [email protected] (W. Zhao). 0033-3506/$ - see front matter & 2006 The Royal Institute of Public Health. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2006.04.012 ARTICLE IN PRESS Diabetes and depression: sex and age differences Introduction Diabetes is one of the most prevalent non-communicable diseases globally. In Canada it is a public health problem of potentially enormous proportions. The prevalence of physician-diagnosed diabetes is 4.8% among people aged 20 years and older in Canada.1 With the conservative assumption that one-third of all cases of diabetes are undiagnosed, the total number of Canadians with diabetes was about 1.7 million in 1998–1999.1 About 1.4% of adults developed diabetes during the 4-year period between 1994 and 1998.1 The economic burden of diabetes and its complications in Canada is estimated to be up to $9 billion (US) annually in direct healthcare costs and indirect costs, including lost productivity due to diabetes-related illness and premature death.1 Psychological illness is responsible for considerable disability worldwide. The World Health Organization Global Burden of Disease Survey estimates that, by the year 2020, major depression will be second only to ischaemic heart disease in the amount of disability experienced by sufferers. Many studies have shown that the risk of depression is higher in individuals with diabetes than in those without diabetes.2,3 Known to impair overall functioning and quality of life,4,5 depression has additional importance in diabetes because of its association with poor compliance with diabetes treatment,4 poor glycaemic control,6 and an increased risk for micro- and macro-vascular disease complications.7,8 The presence of concomitant depressive symptoms among people with diabetes is associated with substantially increased health economic burden compared with people with diabetes without depression or depressed people without diabetes. This is because of the increased use of emergency care, outpatient primary care, medical and psychiatric specialty care, medical inpatient care, and higher prescription costs.3,4 The mental health of young individuals with diabetes is of particular concern. A meta-analysis including 20 controlled studies found that the risk of depression in the diabetic groups was two-fold higher than that in the non-diabetic comparison groups.2 This relative risk of depression is greater than found in most other chronic diseases.3 The results from previous studies suggest that younger age was associated with depression,9 and the primary age of risk for major depression was age 25–40 years in the general population.10 A controlled prospective study found that type 1 diabetes mellitus was associated with more protracted depressions and a higher recurrence rate among 697 young women, compared with depressed psychiatric patients without diabetes.11 Patients with type 1 diabetes aged 16–25 years were found to be more socially isolated than a healthy comparison group.12 Young diabetic women with depression had higher ambulatory care use and filled more prescriptions than their counterparts without depression.3 However, only 27% of them monitored blood glucose reasonably well, and only 8% of them had a glycated haemoglobin concentration within the optimal range.13 Treatment of depression in people with diabetes resulted in improvements in self-efficacy, self-care behaviours, glycaemic control, patient satisfaction, and quality of life.14 The effect of sex and age on the association between depression and diabetes has not been previously reported. Monitoring the psychological status of young people with diabetes may help to identify diabetic patients at risk for psychiatric disorder, and facilitate prevention or treatment efforts.11 Identifying the sex and age difference in the association between diabetes and depression may be useful for developing targeted intervention strategies for depression control and prevention in people with diabetes. We therefore explored the associations between gender, age, depression and diabetes in a national cross-sectional survey. Methods This analysis was based on cross-sectional data from the Canadian National Population Health Survey (NPHS), conducted by Statistics Canada (Ottawa, Ontario) in 1996–1997. The target population of NPHS was household residents 12 years of age or more in all provinces, excluding people living in Indian Reserves, Canadian Forces Bases, and some remote areas of Quebec and Ontario. The 1996–1997 NPHS was collected mainly by telephone. The NPHS used a multi-stage stratified sampling design to draw a representative sample of 95 466 households, and 78 751 households participated in the survey, with a national response rate of 82%. In all provinces, except Quebec, the Labor Force Survey design was used to draw the sample. In Quebec, the Enque ˆte Sociale et de Sante conducted by Sante´ Quebec in 1992–1993, with a two–stage design similar to that of the Labor Force Survey, was used. In each household, all members were asked to complete a short general questionnaire, and one person was randomly selected for a more in–depth interview. The survey included ARTICLE IN PRESS 698 questions related to the determinants of health, health status and use of health services.15 This analysis was based on data from of 53 072 people aged 20–64 years. Depression was assessed by the depression scale from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Short-Form (CIDI-SF).15 The CIDI is a structured diagnostic instrument that was designed to produce diagnoses according to the definitions and criteria of both DSM-III-R (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) and the Diagnostic Criteria for research of ICD-10.15 The CIDI-SF is a subset of items from CIDI that measures major depressive symptoms during the previous 12 months. A complete copy of the CIDI-SF questions and scoring instructions is available from the World Health Organization website www.who.int/msa/ cidi/index.htm). Depression was considered to be present when depression scale score was greater than or equal to 5. Respondents who answered affirmatively to the question ‘do you have diabetes diagnosed by a health professional?’ were considered to have diabetes. The association between diabetes and depression was examined separately in study participants aged 20–39 and 40–64 years. We categorized the participants according to other potential risk factors for depression in the study, which were similar to a previous report by Chen et al.16 Self-reported body weight and height were used to calculate body mass index (BMI): BMI ¼ weight (kg)/height (m2). BMI values were categorized into the four groups:o20, 20.0–24.9, 25.0–29.9, and X30.0 kg/m2. Participants in the low education category had not proceeded beyond secondary school, and the high education category included particpants who had been admitted to college or university, as well as those with a postsecondary school certificate or diploma. Participants were classified into low-, middle-, and highincome groups based on total household income adjusted for number of household members (appendix A). A positive history of allergy was defined by an affirmative response to either of the following questions: ‘do you have any food allergies diagnosed by a health professional?’ or ‘do you have other allergies diagnosed by a health professional?’ A regular alcohol drinker was defined as a person who reported drinking alcoholic beverages at least once a month. Daily smokers were respondents smoking cigarettes every day at the time of survey, former smokers were those smoking cigarettes daily in the past but not smoking at the time of survey; otherwise, participants were classified as non- or occasional smokers. A regular exerciser was defined as a person who engaged in physical activities that lasted more than 15 min at W. Zhao et al. least 12 times a month. Other variables included in the analysis were region (eastern, central and western Canada), immigrant status (yes, no), marital status (married/common-law/partner, single, widow/divorced/separated), household size (1, 2, 3, or X4 people), and number of bedrooms (o3, X3). The associations between diabetes and depression in different age groups were examined for men and women separately and jointly. We calculated the prevalence of depression according to various factors. Multiple logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between diabetes and the prevalence of depression before and after controlling the potential confounders. Potential interactions of diabetes with other factors were tested at an alpha level of 0.1 in a multiplicative scale. We calculated the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for depression associated with diabetes and corresponding 95% confidence intervals by sex and age groups. The NPHS used a complex survey design. A design effect is defined as the ratio of the estimated variance taking into account the nature of the survey design to a comparable estimate of variance based on a simple random sample of the target population.16 In the present study, the Rao–Wu bootstrap method was used for variance estimation to take both the population weights and design effects into consideration, as described in detail elsewhere.16 Statistical analyses were carried out with SAS V8. Results The prevalence of diabetes is presented in Table 1. Diabetes was found to be higher in people aged 40–64 years than in people aged 20–39 years (men: 4.7% vs. 0.5%; women: 3.5% vs. 0.8%, respectively). In contrast, people aged 20–39 years had a slightly higher prevalence of depression than those aged 40–64 yeas of age (men: 3.1% vs. 2.9%; women: 6.6 vs. 5.4, respectively) (Fig. 1). The prevalence of diabetes and depression by the potential confounders for the relation between diabetes and depression is also shown in Table 1. Participants with BMI X 30 kg/m2 had a higher prevalence of diabetes than participants with lower BMI; participants with BMIo20 kg/m2 or X30 kg/m2 had higher prevalence of depression than others in both sexes. Participants with low educational level, smaller number of bedrooms (o3) and low income had a higher prevalence of both diabetes and depression than those with high educational level, ARTICLE IN PRESS Diabetes and depression: sex and age differences 699 Table 1 Prevalences (%) of diabetes and depression, by potential risk factors, among individuals aged 20–64 years based on cross-sectional observations from 1996 to 1997 National Population Health Survey, Canada. Men N Age (years) 20–39 40–64 Region Eastern Central Western BMI (kg/m2) o2 0 20–24.9 25–29.9 X30 Unknown Physical activity Regular exercise Not regular Unknown Smoking Non-/ occasional smoker Former smoker Daily smoker Unknown Drinking Regular drinker Not regular drinker Unknown Allergy Any allergy ‘yes’ No or unknown Educational level Secondary or lower Postsecondary or higher Unknown Size of household 1 person 2 people 3 people X4 people Number of bedrooms o3 X3 Unknown Income Low Middle High Not stated Marital status Married Single Women Diabetes Depression Case Case N % N % 12 991 12 386 89 595 0.5 4.7 448 367 3.1 2.9 1145 14 358 9874 29 406 249 3.4 2.5 2.4 34 445 336 615 8881 11 602 3965 314 12 148 280 235 9 3.2 1.5 2.5 5.7 2.1 14 227 10 524 626 348 301 35 11 232 6398 7655 92 N Diabetes Depression Case Case N % N % 14 399 13 296 142 539 0.8 3.5 1049 779 6.6 5.4 3.0 2.8 3.6 1330 15 906 10 459 35 382 264 2.7 2.1 2.0 69 1013 746 5.8 5.5 7.2 40 304 331 139 1 8.9 1.2 1.3 2.7 0.2 3190 12 133 6645 3316 2411 17 143 211 241 69 0.3 0.9 3.1 6.6 2.5 252 742 446 283 105 7.0 5.5 6.5 7.7 3.0 2.8 2.2 3.7 466 346 3 3.0 3.3 0.3 17059 10 250 386 367 301 13 2.0 2.3 3.4 1046 778 4 6.0 6.4 0.3 234 287 159 4 1.8 3.8 2.6 3.4 229 195 390 1 2.0 1.9 5.5 2.6 14 303 6145 7162 85 340 191 148 2 1.9 2.8 1.9 2.2 671 403 754 0 4.0 6.2 10.2 0.0 17 808 7296 273 341 335 8 2.1 3.7 1.6 541 273 1 2.9 3.6 0.1 13 557 13 905 233 167 510 4 0.8 3.4 0.6 934 890 4 6.2 6.0 0.8 5302 20 075 134 550 1.8 2.8 240 575 3.6 2.9 8708 18 987 269 412 2.2 2.0 767 1061 8.7 4.9 9488 15 659 230 320 358 6 3.3 2.2 1.5 309 503 3 2.8 3.2 0.9 10 113 17 391 191 332 341 8 3.0 1.5 3.4 649 1169 10 6.5 5.8 4.1 5048 7504 4788 8037 153 294 119 118 3.2 3.9 2.3 1.7 314 199 120 182 7.6 3.1 2.3 2.0 4514 9106 5517 8558 181 248 124 128 3.6 2.3 2.3 1.4 393 580 394 461 7.9 6.1 6.9 5.0 7635 17 236 506 240 431 13 3.3 2.3 2.6 373 432 10 5.3 2.2 1.6 8482 18 614 599 272 398 11 2.6 1.9 1.4 710 1097 21 6.8 5.8 2.3 2337 5187 12 851 5002 90 147 316 131 3.5 2.4 2.5 2.4 181 211 311 112 6.8 3.5 2.5 1.6 3836 6161 12 131 5567 153 176 221 131 3.7 2.6 1.3 2.1 459 445 643 281 11.6 6.2 4.9 4.5 16 086 6809 482 101 3.0 1.2 335 311 2.2 3.7 17 411 5731 412 88 2.1 1.4 855 487 4.7 7.1 ARTICLE IN PRESS 700 W. Zhao et al. Table 1 (continued ) Men N Prevalence of depression (%) Widow, divorced or separated Not stated Immigrant Yes No Unknown Women Diabetes Depression Case Case N % N % 2434 101 3.8 167 8.9 48 0 0.0 2 3919 21 331 127 124 559 1 3.2 2.4 0.5 114 698 3 Diabetes Depression Case Case N % N % 4476 181 3.4 482 11.3 3.0 77 0 0.0 4 2.8 2.0 3.3 1.8 4311 23273 111 112 565 4 2.7 2.0 2.3 209 1614 5 4.0 6.5 3.3 Discussion 25 20 15 10 5 0 N 20-39 40-64 Male 20-39 40-64 Female 20-39 40-64 Total Figure 1 The prevalence of depression in subgroups. Blank, diabetes; black, non-diabetes. larger number of bedrooms (X3) and middle or high income. A higher prevalence of depression in people with diabetes compared with those without is shown in Table 2. The difference in the prevalence of depression between diabetic and non-diabetic individuals was more evident in younger groups for both sexes. The prevalence of depression tended to be higher in women than in men in all age groups except for the category of younger diabetic patients, which had a limited sample size. Table 2 shows that diabetes was positively associated with depression, and the association was stronger among younger adults than among older adults: the odds ratio was 4.19 (95% CI 0.99, 17.70) in people aged 20–39 years and 2.07 (95% CI 1.08, 3.97) in people aged 40–64 years, respectively. This age difference was seen in both sexes: the odds ratios were 8.30 (95% CI 0.72, 95.17) for the younger group and 2.67 (95% CI: 0.90, 7.94) for the older group in men, and in women they were 2.52 (95% CI 1.19, 5.32) and 1.62 (95% CI: 0.65, 4.06), respectively. In most studies investigating the association between diabetes and depression, age is usually adjusted for, and the modifying effect of age is not examined.9,17 In this paper, we have focused on the sex and age differences in the association between diabetes and depression. On the basis of cross-sectional data from the NPHS in 1996–1997, our analyses suggest that diabetes was significantly associated with the prevalence of depression in young women, and the association tended to be stronger among younger adults than among older adults. A meta-analysis including 20 controlled studies found that the presence of diabetes doubled the odds of depression.2 The results of a 5-year follow-up study that included patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes strongly suggested that the course of depression in people with diabetes was perhaps worse than the course of depression among medically well individuals.18 The lifetime prevalence of major depression among adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus and type 2 diabetes mellitus ranges between 14.4% and 32.5%.6,19 Although some studies that were limited to type 2 diabetes mellitus have shown a positive relationship between type 2 diabetes mellitus and depression,18,19 individuals with type 1 diabetes mellitus have long been viewed as particularly prone to depression.11 A 10-year follow-up study10 identified an effect of type 1 diabetes mellitus on lower perceived competence in young adults, which could represent early signs of what may become more clear-cut presentations of self-esteem problems, as well as depressive symptoms and illnesses, later in adulthood. On e study reported that major depressive disorder (MDD) was the most prevalent psychiatric morbidity among young people with childhood-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus, with a ARTICLE IN PRESS Diabetes and depression: sex and age differences 701 Table 2 Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence interval for the prevalence of depression associated with diabetes by sex and age among people aged 20–64 years based on cross-sectional observations from 1996–1997 National Population Health Survey, Canada. Age (years) Unadjusted OR 95% CI Adjusted OR* 95% CI Men 20–39 40–64 9.66 2.28 0.76, 122.41 0.94, 5.54 8.30 2.67 0.72, 95.17 0.90, 7.94 Women 20–39 40–64 2.33 1.76 1.12, 4.85 0.78, 3.94 2.52 1.62 1.19, 5.32 0.65, 4.06 Total 20–39 40–64 4.30 1.87 1.43, 12.91 1.04, 3.37 4.19 2.07 0.99, 17.70 1.08, 3.97 OR, odds ratio; *, adjusted for region, BMI, physical activity, smoking status, drinking status, allergy, educational level, size of household, number of bedroom, income, marital status and immigrant status. cumulative probability of 27.5% the tenth year after diagnosis.11 The prevalence of depression in children and adolescents with diabetes is two to three times that of peers without diabetes.7,20 The reasons for the stronger association between diabetes and depression in people aged 20–39 years, compared with older age groups, are unclear; however, there are several possible explanations. Different types of diabetes may have different associations with depression. The mean age of onset for type 1 diabetes mellitus was 17.3 years, and type 2 diabetes mellitus is most common in adults over the age of 40 years.18 Younger adults were more likely to have adolescence-onset diabetes. The prevalence of depression among adolescents with diabetes is three times higher than that among peers without diabetes.20 The following reasons may explain the significantly higher odds ratio in this particular population. First, for adolescents, the challenge of diabetes, such as, fear of diabetes-related complications and helplessness in avoiding them, is combined with the developmental task of adapting to puberty and a changing body image, peer-group pressure, autonomy from the parents and identity formation.21 This combination of challenges may increase their risk for a depression episode. Second, the treatment for type 1 diabetes mellitus requires individuals to adhere to a complex set of treatment regimens, including daily multiple insulin injection, monitoring blood glucose value, adherence to specific dietary guidelines and attending regular medical exams. This heavy burden of treatment may increase risk for depression. Third, a number of risk factors have been identified to increase the likelihood of depression during adolescence, including female gender, family dysfunction and stressful experience. One stressful experience that may increase risk for depression in adolescents is diabetes.21 The history of depressive episode or stressful experience in adolescence is a risk factor for depression or recurrence of depression in young adults with diabetes.21 In addition, the higher odds ratio in young adults may result from a variety of inherent differences between type 1 diabetes mellitus and type 2 diabetes mellitus, including type of treatment, the influence of the disease on physical and psychological functioning and the quality of life resulting from the disease. For example, patients with type 2 diabetes who are treated with diet only or oral agents may be less likely to have depression.22 Our data showed that the percentage of patients taking insulin was 48.9% in people aged 20–39 years and 29.7% in people aged 40–64 years, respectively. Early adulthood is the developmental period during which individuals assume a greater degree of independent functioning and take on adult roles; a chronic illness such as type 1 diabetes mellitus could impede these aspects of life-cycle development.10 It is also possible that type 1 diabetes mellitus places patients at risk for a depressive disorder through a biological mechanism linking the metabolic change of diabetes to changes in brain structure and function.23 The cross-sectional design of the present study did not permit us to determine the temporal relation between onset of depression and onset of diabetes. However, previously published studies have found that the typical temporal sequence may ARTICLE IN PRESS 702 differ between type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. In a cohort study of adults with diabetes, the mean age of type 2 diabetes mellitus onset was 37.3 years, and the mean age of depression onset in patients with type 2 diabetes was 28.6 years.18 It is possible that depression may lead to lack of exercise and poor dietary habits, which in turn increase risk of diabetes. A prospective populationbased study showed that major depressive disorder predicted the onset of type 2 diabetes.17 In patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus, the mean age of diabetes onset was 17.3 years and the mean age of depression onset was 22.1 years.18 No study has shown whether the onset of diabetes in childhood or adolescence contributes to the risk for onset of depression.17 Some studies have observed that a surplus of hormones antagonizing insulin action is present during severe depression, including epinephrine, growth hormone and cortisol.24,25 In a 5-year follow-up study, poor metabolic control (mean glycated haemoglobin 11.2%) was reported in the psychiatrically ill group of people with diabetes at both the baseline and follow-up evaluations, compared with a mean glycated haemoglobin of 9.0% in patients with diabetes without documented psychiatric illness. It was suspected that depression and diabetes may interact at basic biologic levels, perhaps in some reciprocal fashion.18 Although some studies indicate that depression may occur secondary to the hardship of advancing diabetes,2 a 5-year follow-up study found no significant differences at baseline and at followup in the prevalence of diabetes complication between depressed and non-depressed patients (nephropathy, retinopathy and neuropathy; each p40:2).18 However, it did not rule out the possibility that depression may be more closely related to other unmeasured indices of advancing disease (e.g. changes in cerebral vasculature or specific limitations in function (e.g. blindness or erectile dysfunction).18 In addition, the present study did not find an association between diabetes and depression in men; however, owing to the relatively small sample size and the consequently limited statistical power of the present study, studies with large sample size are needed to further investigate this association in men. The comorbidity of diabetes and depression among young people aged 20–39 years is a serious problem. Depression alone carries significant potential for disability, but, when combined with W. Zhao et al. diabetes, the comorbidity carries the potential for serious long-term consequences. Many investigators have found that people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes with depression have significantly worse glycaemic control than people with no history of any psychiatric illness.6,21 Prolonged poor glycaemic control results in more rapid onset and progression of retinopathy, neuropathy and nephropathy, which have been linked with decreases in quality of life26,27 and increased mortality.28 Conclusion This analysis, based on cross-sectional data from the Canadian National Population Health Survey in 1996–1997, suggests that diabetes is positively associated with the prevalence of depression, and the association is stronger among young adults than among older adults. The age difference is important for several reasons. Depression in young people with diabetes is associated with a significant increase in suicide and suicidal ideation.29 The recurrence and course of depression may be more severe than that in older groups.11 Young people with diabetes and depression are likely to have other comorbid conditions, such as eating disorders, adjustment disorders or anxiety disorders.11 An eating disorder may be life-threatening for people with diabetes, and early treatment may be particularly beneficial for young people with diabetes.11 Therefore, young people with diabetes should be monitored for psychological status. Prevention, early diagnosis and early treatment of depression for them, are extremely important. Acknowledgements This research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canadian Diabetes Association. Yue Chen is a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Investigator Award recipient. Ronald J. Sigal was a Canadian Institutes of Health Research new Investigator Award recipient, and currently holds the OHRI Research Chair in Lifestyle Research. Appendix A. The classification of income (Table A1) ARTICLE IN PRESS Diabetes and depression: sex and age differences 703 Table A1 Category Household size The limit of income 1–4 5 or 1 or 3 or 5 or more 2 4 more o$10 000 o$15 000 $10 000–14 999 $10 000–19 999 $15 000–29 999 1 or 2 3 or 4 5 or more $15 000–29 999 $20 000–39 999 $30 000–59 999 1 3 5 1 3 $30 000–59 999 $40 000–79 999 $60 000–79 999 $60 000 or more $80 000 or more Low income Lowest Lower middle Middle income High income Upper middle Highest References 1. Health Canada. Diabetes in Canada, 2nd edn. Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Control, Population and Public Health Branch, Health Canada, 2000; Cat. No. H49-121. 2. Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, et al. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a metaanalysis. Diab Care 2001;24:1069–78. 3. Egede LE, Zheng D. Comorbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diab Care 2002;25:464–70. 4. Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med 2000;160: 3278–85. 5. Rubin RR, Peyrot MF. Quality of life and diabetes. Diab Metab Rev 1999;5:205–18. 6. Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, et al. Depression and poor glycaemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diab Care 2000;23:934–42. 7. Carney RM, Rich MW, Freedland KE, et al. Major depressive disorder predicts cardiac events in patients with coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med 1988;50:627–33. 8. Kovacs M, Mukerji P, Drash A, et al. Biomedical and psychiatric risk factors for retinopathy among children with IDDM. Diab Care 1995;18:1592–9. 9. Egede LE, Zheng D. Independent factors associated with major depressive disorder in a national sample of individual with diabetes. Diab Care 2003;26:104–11. 10. Jacobson AM, Hauser ST, Willett JB, et al. Psychological adjustment to IDDM: 10-year follow-up of an onset cohort of child and adolescent patients. Diab Care 1997;20: 811–8. 11. Kovacs M, Goldston D, Obrosky DS, et al. Major depressive disorder in youths with IDDM. A controlled prospective study of course and outcome. Diab Care 1997;20:45–51. 12. Lloyd CE, Robinson N, Andrews B, et al. Are the social relationships of young insulin-dependent diabetic patients affected by their conditions? Diab Med 1993;10:481–5. or or or or or 2 4 more 2 more 13. Kokkonen J, Lautala P, Salmela P. The state of young adults with juvenile onset diabetes. Int J Circumpolar Health 1997;56:76–85. 14. Delamater AM, Jacobson AM, Anderson B, et al. Psychosocial therapies in diabetes. Diab Care 2001;24:1286–92. 15. Statistics Canada. National Population Health Survey 1996–1997. Public use microdata files. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Health Statistics Division. 16. Chen Y, Dales R, Tang M, et al. Obesity may increase the incidence of asthma in women but not in men: longitudinal observations from the Canadian National Population Health Surveys. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:191–7. 17. Eaton WW, Armenian H, Gallo J, et al. Depression and risk for onset of type II diabetes: a prospective population-based study. Diab Care 1996;19:1097–102. 18. Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Clouse RE. Depression in adults with diabetes: results of 5-year follow-up study. Diab Care 1988;11:605–12. 19. Gavard J, Lustman PJ, Clouse RE. Prevalence of depression in adults with diabetes. Diab Care 1993;16:1167–78. 20. Kokkonen K, Kokkonen ER. Mental health and social adaptation in young adults with juvenile-onset diabetes. Nord J Psychiatry 1995;49:175–81. 21. Grey M, Whittemore R, Tamborlane W. Depression in type 1 diabetes in children nature history and correlates. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:907–11. 22. de Groot M, Jacobson AM, Samson JA, et al. Glycemic control and major depression in patients with type 1 and type 2 diab mellitus. J Psychosom Res 1999;36: 425–35. 23. Jacobson AM, Samson JA, Weinger K, et al. Diabetes, the brain and behavior: is there a biological mechanism underlying the association between diabetes and depression? Int Rev Neurobiol 2002;51:455–79. 24. Wyatt RJ, Portnoy B, Kupfer DJ, et al. Resting plasma catecholamine concentrations in patients with depression and anxiety. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1971;24:65–70. 25. Mueller PS, Heninger GR, McDonald RK. Intravenous glucose tolerance test in depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1969;21: 470–7. ARTICLE IN PRESS 704 26. Lloyd CE, Matthews KA, Wing RR, et al. Psychosocial factors and complications of IDDM. The Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications Study. VIII. Diabetes Care 1992;15: 166–72. 27. de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, et al. Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2001;63:619–30. W. Zhao et al. 28. Krolewski AS, Warram JH. Epidemiology of late complication of diabetes. In: Kahn CR, Weir GC, editors. Joslin’s diabetes mellitus. 13th edn. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1994. 29. Goldston DB, Kelley AE, Reboussin DM, et al. Suicidal ideation and behavior and noncompliance with the medical regimen among diabetic adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36:1528–36.

© Copyright 2026