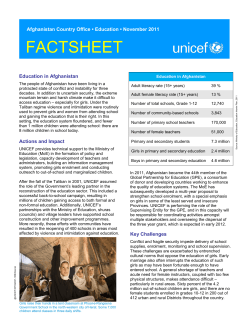

Education for all and children who are excluded