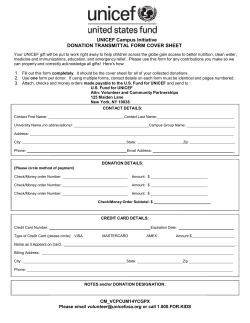

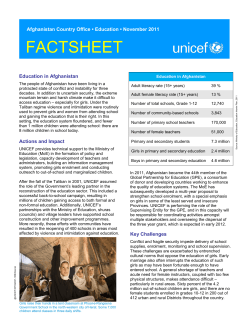

A Human Rights-Based Approach To Education For All, UNICEF