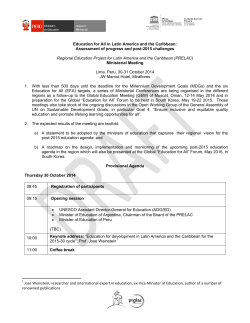

The world we want to see: perspectives on post-2015