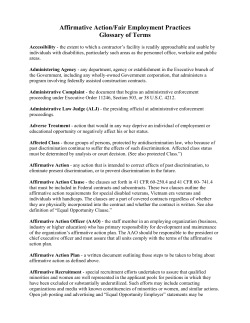

Children’s Rights: Equal Rights? Save the Children