israel RepoRt

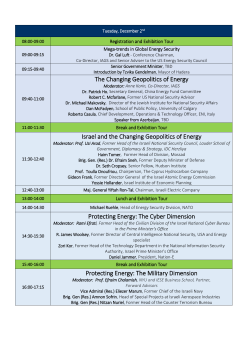

israel Report WHERE HISTORY BECOMES ART The personal is political for many Israeli artists becoming ever more active on the international scene. BY LILLY WEI Israel, a nation the size of New Jersey, has changed dramatically since its inception in 1948. The population—now close to 7.5 million, almost 10 times the founding total—is roughly 70 percent Jewish, 20 percent Arab and 10 percent other. The economy remains vibrant despite the recent worldwide downturn, and Israeli military might is both admired and hated. This is an atypical country, Ron Pundak, the director general of the Peres Center for Peace and one of the negotiators of the 1993 Oslo Accord, said to me in conversation, reiterating the opinion of many. The state was founded on a moral imperative and a double-edged calamity, with the Holocaust on one side and the eviction of the Palestinians on the other. Indeed, what Israel celebrates as its birthday is called al-nakba, the catastrophe, by the Palestinians. Today’s young Israelis are less rooted in the past than their predecessors. Nevertheless, Gilad Ratman, an emerging video artist with an MFA from Columbia University in New York, where he currently resides, feels that history is “injected into us at birth.” Although he recently had a solo show exploring the grotesque at the New Media Center of the Haifa Museum, he is not wedded to Israel—nor are his peers, many of whom are settling in London, Berlin, Amsterdam and other international art centers. Reexamining the development of their country and the region, these artists often adopt a critical, independent point of view as they move toward a post-national frame of mind. They are able to engage in discourse beyond the reflexively patriotic and partisan, and to see Israeli politics, religion and ethnic issues coolly, in shades of gray, while remaining sincerely saddened by the violence, the deaths. Looking at the work of some of these artists during my visits over a year ago and last fall, and talking to them individually in Israel and abroad, I sense that they have inherited a tremendous subject simply by being born in an uneasy, unstable land with its collision-course histories, crisscrossed by deep fault lines of distrust and outrage, anxiety and fear. Despite all this, of course, ordinary life goes on there much as it does anywhere else—although pervaded by an exceptional intensity and tenacity. In fact, some boosters, holding that Israel is less isolated than it once was, would like to make Tel Aviv a kind of Miami on the Mediterranean, ignoring the flashes of violence only a few miles away. More temperately, Mordechai Omer, the longtime director and curator of View of Art TLV 09, the Tel Aviv Biennial of Contemporary Art, showing Shelly Federman’s outdoor installation Aberstien—Floating Wall, 2009. Photo Omer Messinger. the Tel Aviv Museum and an eloquent advocate for modern and contemporary art in Israel, describes the confidence of Israeli artists as being at an all-time high. Doron Sebbag, whose world-class holdings make him the most prominent of a growing number of younger collectors of contemporary art in Israel, cites the positive effect of increasing government and private sector support, and notes a huge change on the commercial scene. In the 1980s the country had only a handful of contemporary galleries; today it boasts at least 40 or 50, many with international reputations—such as Dvir Gallery and Sommer Contemporary Art, both in Tel Aviv. And while $30-40,000 was once considered a substantial amount to pay for a work of Israeli art, prices January’10 art in america 51 These artists have inherited a tremendous subject simply by being born in an uneasy, unstable land crisscrossed by distrust and outrage, anxiety and fear. now can reach hundreds of thousands, even half a million, U.S. dollars. Citing artists such as Yael Bartana, Mika Rottenberg, Guy Ben-Ner and Omer Fast, as well as others like Yigal Ozeri who are a generation older, Sebbag contends that “Israeli art is finally becoming original.” Over 20 years ago, Zvi Goldstein, a Romanian-born conceptualist and sculptor who has lived in Israel since 1958, stressed to me in an interview for Art in America [July 1989] that, worldwide, the energy from the periphery is as great as that at the center. More than ever, that observation holds true in Israel, even though what might be considered the periphery has shifted as globalization continues its advance, creating new centers as it goes. Tel Aviv, the country’s most vibrantly cosmopolitan and politically liberal city, celebrated the centennial of its founding last fall (a year after the nation’s 60th birthday) by presenting, among other festivities, an impressive array of exhibitions and performances by Israeli and international artists, the former in many instances outshining their guests, especially in photography, video and video installations. The centerpiece of these activities was Art TLV 09 [Sept. 10-24, 2009]. The second installment of a new addition to the international biennial circuit, it was part of a regional trifecta: Athens, Istanbul, Tel Aviv. Organizers chose as its symbolically freighted main site the 19th-century Templar compound at the nexus of Neve Tzedek, Tel Aviv’s first Jewish neighborhood; the old Arab city of Jaffa; and the formerly industrial Florentin area, now transformed into a modern residential zone. The biennial—encompassing some 50 artists in its core show and another 40 or so in related exhibitions—took Tel Aviv itself as its theme, prompt52 art in america January’10 Israel report ing reflections on urbanization and its ramifications, both literal and metaphoric, and raising questions about history, politics and identity—especially the Palestinian issue, never far from anyone’s mind in this region. Israeli artist Shelly Federman, for example, scattered Styrofoam wedges on the ground, where they evoked lounge chairs and surfboards but also recalled slabs of the West Bank’s partition wall. Palestinian writer Laila El-Haddad and Israeli designer Mushon Zer-Aviv Above, view of projection on a ship’s sail for “Ex-Territory.” The first event in this itinerant five-year project was held during Art TLV 09. Opposite top, two stills from Fahed Halabi and Ala Farhat’s Working Day, 2009, video, 16 minutes; in “Men in the Sun” at the Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art. Opposite bottom, Gilad Ratman: The Way We Did Che Che, 2005, video, 24 minutes; at the Haifa Museum of Art. Courtesy Braverman Gallery, Tel Aviv. collaborated on You Are Not Here, a conceptual “tour” connecting Tel Aviv to Gaza City. Given a double-sided map of the two towns, the “metatourist” could hold it up to the sun so that the plans were superimposed. To visit a Gaza location, say the Unknown Soldier Park, one would walk to the corresponding location on the Tel Aviv map, in this instance the Helena Rubenstein Pavilion, and there find a telephone number stickered on a pole. Calling the number, one got an audio founder of modern Zionism), offered an elegant installation of videos, sculptures and photographs by German artist Gregor Schneider from his ongoing “Haus u r” project, a suite of art- and memento-laden rooms in his house in Rheydt, Germany. But the highlight at the museum was “Men in the Sun,” an occasionally humorous but more often sobering exhibition of works by 13 Palestinian artists who live in Israel. One standout was Working Day, by Fahed Halabi and Ala Farhat, a video tour of the Gaza site—an account, conceived by El-Haddad, that was factual yet extremely personal and partisan. The aim of the project was to inform and engage the residents of Tel Aviv about “a reality they are responsible for,” according to Zer-Aviv, the Gaza known to most Israelis only through the media—or, to some, as the site of much too real combat encounters. The Herzliya Museum of contemporary Art, in nearby Herzliya (an upscale city named after Theodor Herzl, the about a crew of Palestinians restoring the facade of a sun-drenched synagogue. Suddenly, a worker recites, in deadpan fashion, his recent experience in Gaza—which included seeing his friend’s head blown away as the two ran from Israeli military fire. The exhibition’s title repeats that of a controversial 1963 novel by Palestinian writer and activist Ghassan Kanafani, who was killed in a car bomb explosion in Beirut in 1972, allegedly at the hands of Israel’s covert intelligence agency, the January’10 art in america 53 Mossad. The book, treated as a touchstone in the show’s catalogue, follows the journey of three Palestinian refugees of different ages who leave their refugee camps to seek work in Kuwait. Without travel permits, they hide in the empty water tank of the truck that is transporting them as they approach a guard station at the Iraq-Kuwait border. The soldiers take their time and the stowaways die in the killing heat. The story ends with the anguished cry of the truck driver: “Why didn’t you knock on the sides of the tank? Why didn’t you bang the sides of the tank? Why? Why? Why?” Another politically based enterprise is “Ex-Territory,” a two-year initiative that was launched in September in international waters off Tel Aviv with screenings of videos by Arab and Israeli artists projected onto the sails of a catamaran, to be watched from another boat that ferries viewers out to the site. The Ex-Territory group, composed of four Israeli members, plans to provide a politically neutral floating platform for unrestricted cultural exchange while sailing throughout the Mediterranean, with future events scheduled for the coastal regions of Turkey and Egypt, pending funding. Maayan Amir, one of the founders, explained, “Arab artists will not exhibit art in Israel because of the political situation. We are trying to find a solution to this problem by meeting in extra-territorial waters, and offering a nonhistorical space for dialogue.” That seems only a partial solution, however, given that the participating Arab artists could not be named for fear of reprisals against them. Still, partial solutions are better than none. The artists I have chosen to examine more closely, most of them multidisciplinary, with an emphasis on photography and video, range Right, Barry Frydlender: Waiting (“End of Occupation?” Series No. 1), 2005, color photograph. Below, Frydlender: Pool, Malibu, 2008, color photograph. Photos this spread courtesy Andrea Meislin Gallery, New York. from first-generation native Israelis in their mid-50s to younger colleagues in their late 30s. Each has his or her own approach to Israeliness, including attempts to more or less ignore it—except that none of them truly can. Ultimately, to be an Israeli artist is different from being an artist from any country without such a burdened history, fraught present and uncertain future. Barry Frydlender and Michal Rovner, two artists of the first generation to achieve international recognition, are discussed below. The next wave—represented by Adi Nes, Eliezer Sonnenschein, Sigalit Landau, Yael Bartana and Keren Cytter—will be the subject of a future installment. Barry Frydlender (b. 1954), one of Israel’s most celebrated photographers, with recent solo shows at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Jewish Museum in Paris, lives and works in his native Tel Aviv. His studio in an industrial building is a cluttered 54 art in america January’10 Israel report work space, not a white-box showroom. On the walls, or soon unrolled for me to view, were numerous photographs characterized by disconcerting and deceptive precision, preternatural light, stunning clarity and great formal beauty. The compositions, usually horizontal panoramas, present such views as the local neighborhood seen from the studio window, Tel Aviv beaches, the Gaza Strip and an active convenience store open to the street. These informationrich images are meticulously pieced together on a computer from multiple digital photos—sometimes dozens, sometimes hundreds—accumulated consonant with the partially fictive nature of the composite scene. Signs in Hebrew read “don’t betray us” and “why?” The titular song is said to have been sung by the ancient Israelites when they reached the Red Sea, with the Pharaoh’s forces in determined pursuit. As the story goes, God heard his people, parted the waters and saved them. Ironically, the army that confronts the Israelis in Frydlender’s photo is their own, and the waters do not part. The scene is both biblical and up-to-date. In keeping with current political complexity, it’s not clear if salvation or stalemate is at hand. While not as widely traveled as some Barry FryDlender’s composite photographs, in which figures may appear in several locations within the same frame, evoke complex interweavings of past and present. over varying intervals of time. The works appear seamless at first, but eventually many anomalies become evident: a figure appearing in several locations within the same frame or various figures placed incongruously near one another, their shadows indicating separate shots from different times of day. Frydlender likens the viewing process to turning pages in a book, each section of the image a page, the entire photograph a volume to be patiently read. Other viewers might make a distant formal link with Asian scroll paintings. Several photos depict the forced evacuation of a seaside Israeli settlement in Gaza in 2005. One improbably festive-looking example features people strolling about, entertainers, a few musicians, trailerlike barracks, and a broad sweep of sea and sky. In another, Shirat Ha’yam (Song of the Sea), 2005, a semicircle of Israeli soldiers spreads across the foreground of the work’s 10-foot expanse—the curve, suggesting a stage, of his compatriots, Frydlender has spent a fair amount of time away from Israel, including several months in the Los Angeles area in 2007. There he made a series conveying his vision of Southern California, presented with customary detachment. One image, Pool, Malibu (2008), includes a house with a pool screened by tall trees. Looking down on the green watery rectangle, one can see it as a samplesize memory of the Mediterranean. An earlier aerial photo called Estates (2005) depicts a swimming pool in Israel, an extreme luxury in that desert land. Yet the aquatic indulgence, surrounded by empty lounge chairs, is eerily situated beside an old Jewish cemetery. Frydlender’s composite, time-bending artistic process is a kind of corollary to life in Israel, where past centuries and the present are complexly interwoven. He explained that he works “with and against the tradition of ‘done in the course of my life’ photography—with what is around The works of photographer, video artist and sculptor Michal Rovner (b. 1957, Tel Aviv), who represented Israel at the Venice Biennale in 2003 (alone, after a Palestinian artist whom she asked to share the pavilion with her declined out of concern over alienating his brethren),2 are often described as timeless, elemental and universal, their stark, lyrical beauty earning her an avid international following. Rovner’s best-known videos are haunting, postapocalyptic evocations of desert, sky, fire and air crossed by bands of tiny, stripped-down, silhouetted figures that waver, come together and splinter in what might be oscillations between community and alienation, ritual dancing and war maneuvers. Projected onto walls, tabletlike stones and petri dishes, the works suggest ancient script in motion or, at times, reconfiguring strands of DNA. Despite the videos’ semi-abstraction, associations with the Sisyphean history of Israel and the Middle East are unavoidable, anchoring Rovner’s poetics to ongoing attempts at reconciliation. me and the people I meet, be it in Santa Monica or Tel Aviv. I practice photography as someone else practices tai chi or Islam, so it is not important where I work, although place does have an enormous effect.”1 January’10 art in america 55 Israel report In Living Landscape, Michal Rovner reconstructs the backstory to the founding of Israel, using archival images that recall an eradicated world. Makom I (2006) and Makom II (200708) are simple cubelike shelters (the title means “place” or “home” in Hebrew) built from old stones taken from structures in Jerusalem, Galilee, Haifa, Nablus and Hebron [see A.i.A., June/July ’08]. In an overtly political gesture endorsing co-existence, the works have been repeatedly assembled and disassembled by a crew of Israeli and Palestinian workAbove, Michal Rovner: Living Landscape (detail), 2004-05, video installation, approx. 11 minutes. Left, Rovner: Untitled, 2009, video projection on stone, 26 3⁄4 by 48 3⁄8 inches. Photos this page courtesy PaceWildenstein Gallery. Works this page © Rovner/Artists Rights Society, New York. ers who, laboring together, travel with the pieces whenever they are installed. Rovner’s permanent, site-specific video installation, Living Landscape (2004-05), projected on a triangular wall more than 36 feet high at Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem, is a departure for her. Compiling a record of the daily life of Eastern European Jews, Rovner painstakingly reconstructed the backstory to the establishment of the state of Israel from archival film footage and photographs, producing a vision of an eradicated world. Daily events in the shtetls—children dancing or bent over books in school, women doing housework, men walking in the streets 56 art in america January’10 people] a place where they could live.” Although her main studio has been in New York since 1988, Rovner has never quite abandoned Israel, keeping both a studio and a house in separate neighborhoods outside Jerusalem, where she goes often to develop ideas and gather materials. In a 2003 interview, she told BBC radio host John Tusa that she had to leave Israel to become an artist, and that the center of her life shifted to New York because the city or gathering for prayer, an orchestra fosters ambitions, dreams and indirehearsing—are seen mostly through viduality. But then she began to think windows, Rovner’s video camera scanof Israel with longing and realized that ning the scenes with great tenderness, she did not have to choose between the lingering here and there on chosen faces two places, that she could inhabit both or vignettes. One of the most touching and create a thread between two very disparate realities. As the second installpassages is of two smiling young girls ment of this report will show, Rovner’s shown on a short loop, hands waving in poignant, never-ending farewell. The realization has come much more easily video took three years to make, Rovner to the next generation of artists, those told me, and for her “it born in the 1960s and was the work of a lifetime, 1970s, as they take 1 E-mail correspondence a great and daunting up residence—itself a with the author, Nov. 7, 2009. responsibility.” She did not concept that is increas2 E-mail to the author, Nov. 17, 2009. want to “dwell on death, ingly fluid—in and out but on life, celebrating a of Israel, depending LILLY WEI is a New York-based spirit that might still prevail. writer and independent curator. upon their situation I wanted to give [these and their desires.

© Copyright 2026