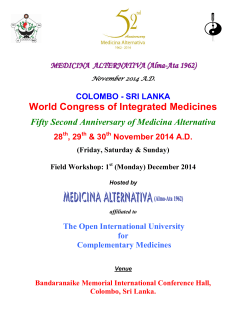

Medico Legal Journal of Sri Lanka