Retrieving the Decorative Program of Villa A

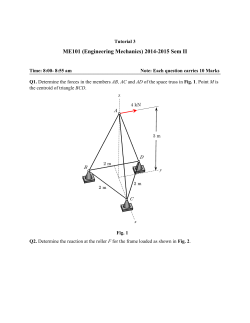

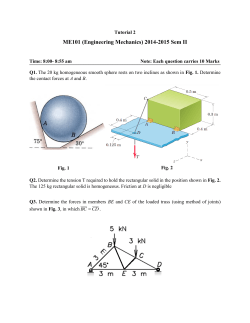

Retrieving the Decorative Program of Villa A (‘of Poppaea’) at Oplontis (Torre Annunziata, Italy): How Orphaned Fragments Find a Home in the Virtual-Reality 3D Model John R. Clarke Abstract Digital reconstruction has reclaimed four Second-Style decorations of Villa A. In processing hundreds of fragments left in storage because they did not fit into what was known of existing walls, we discovered that a group of large fragments defined an ionic upper zone of atrium 5, and that another group belonged to the upper zone of the unexcavated west wall of oecus 15. Archival photographs and drawings, rather than physical fragments, guided digital reconstruction of the nearly destroyed painting in the tympanum of cubiculum 15 and the lost portion of the west wall of triclinium 14. Placing these digitally restored paintings into our navigable 3D model allows scholarly study of the part these decorations played in the decorative ensembles of the Villa. Since 2008, much of my work on Villa A has been aimed at putting in order the locked rooms around the slave’s peristyle (32); over the course of forty years, these rooms (28, 29, 35, 43, 44), originally conceived as secure lockups for fragments of wall painting and excavation finds, accumulated masses of modern materials that got intermixed with the ancient remains. After removing tons of modern debris, we were able clean, study, and catalogue thousands of fragments of painting and stucco. These are the “orphaned fragments” stored in Villa A. In terms of their physical state, there are two basic kinds of fragments: ones that have been consolidated and ones that have received no treatment. In the 1960s and 1970s, the process of consolidation was primitive by modern standards John R. Clarke Fig. 1. Oplontis Villa A, atrium 5, east wall, 1968 (photo Stanley Jashemski 45_24_68. Jashemski Archives, University of Maryland). au: correct? 2 of conservation. Workmen placed the fragment face down a table. They cut down the ancient plaster backing to create a regular surface, then put down galvanized steel wire for reinforcement and applied modern cement to build a new backing. They also formed the wire into loops to serve as hooks for hanging the fragment on the reconstructed wall. Once the fragments from a room were consolidated in this way, the restorers would cement them into the reconstructed wall—presumably in the right position. To aid in this process, restorers traced the outlines of the decorative scheme in the modern cement to guide the positioning of the fragments. Archival photographs provide a sense of how far-reaching this process was. A photograph from the Wilhelmina Jashemski taken by her husband, Stanley, in the summer of 1968, shows the east wall of the atrium (fig. 1). The south half of that wall had collapsed. By 1970, that wall had been reconstructed using blocks of modern tufa (fig. 2). The wall paintings a tourist sees today were salvaged from the debris of that collapse, consolidated, and hung on this reconstructed wall. Although the west wall of the atrium remained standing after excavation, a rare photograph shot in 1966 shows what was visible just after excavations began. Only the tops of the wall have been unearthed (fig. 3). Comparison of this photo with one showing the current state of the wall (fig. 4) reveals The Decorative Program of Villa A at Oplontis that two fragments were found in the volcanic debris and later inserted into the reconstructed wall. It turns out that many Second-Style fragments belonging to the atrium came to light after reconstruction, some of them documented in a photograph dated December 1973 before being consigned to the confusion of the storage rooms around the slaves’ peristyle and only to be rediscovered, measured, and photographed by the Oplontis Project in 2008. One of the project architects, Timothy Liddell, worked with the puzzle presented by these fragments. Using Photoshop and Illustrator, he was able to place a number of the orphaned fragments into a plausible scheme that fits with the architectural perspectives of the standing wall. On the right side of the west wall, there are the faint remains of a column base. Since the only column-capital among the orphaned atrium fragments is Ionic, Liddell hypothesized an Ionic upper order. The pieces fit quite well, but the exact height of the lost Ionic columns must remain speculative (fig. 5). Liddell’s reconstruction is deliberately quite conservative. Martin Blazeby, our partner in King’s Visualisation Lab at King’s College, London, took Liddell’s Ionic upper story and elaborated it on the basis of the other mature Second-Style schemes that he has studied (fig. 6). One can argue the prob- Fig. 2. Oplontis Villa A, atrium 5, east wall, 1970 (photo Archivio Fotografico, Soprintendenza Archeologica di Pompei [henceforth SAP] A3356). 3 John R. Clarke 4 The Decorative Program of Villa A at Oplontis Fig. 3 (opposite, top). Oplontis Villa A, atrium 5, west wall, 1966 (photo SAP De Franciscis 9.397). Fig. 4 (opposite bottom). Oplontis Villa A, atrium 5, west wall, 2009 (photo Paul Bardagjy). Fig. 5 (left). Oplontis Villa A, atrium 5, west wall. Reconstruction (drawing Timothy Liddell). ability of various elements, but taken as a whole Blazeby’s reconstruction helps us imagine—above all—the extraordinary height of the atrium’s decoration—part and parcel of the regal allusions typical of the mature Second Style.1 When Liddell completed his work on the west wall of atrium 5, several fragments were left over that did not fit into his reconstruction. We catalogued them, hoping that we would find a place where they might fit someday. It was only in May of 2013 that I discovered the last hoard of orphaned Fig. 6 (below). Oplontis Villa A, atrium 5, west wall. Reconstruction (Martin Blazeby). 5 Fig. 7. Oplontis Villa A, oecus 15, east wall (reconstruction Timothy Liddell, with queries). John R. Clarke 6 The Decorative Program of Villa A at Oplontis fragments, hidden under a tower of crates in another storage room. They presented an enigma. When assembled, the pieces presented redundant elements belonging to oecus 15. The work of placing these fragments began by photographing all the fragments to scale, then manually arranging them on the floor, with a blowup image of the existing east wall of oecus 15 as a guide. It soon became clear that the redundant elements could not fit on the east wall of the room—the Fig. 8. Oplontis, Villa A, cubiculum 11, north alcove, tympanum, 2009 (photo Paul Bardagjy). Fig. 9. Oplontis, Villa A, cubiculum 11, north alcove, tympanum, 1966 (photo SAP DeFranciscis 9.82). 7 John R. Clarke 8 only wall fully uncovered by the excavations. This wall is quite impressive, the tallest Second Style decoration in the Villa, at nearly 6 m. Although a tunnel in the southwest corner of the room identified the southwest corner the west wall, the remainder still lies buried under the modern street. It turns out that this group of new fragments—along with several that Liddell could not fit into the atrium reconstruction— belonged to the upper zone of this unexcavated west wall. It is probable that the earthquakes that detached and flipped the upper two-thirds of the east wall must have dislodged the fragments of the west wall, mixing them with volcanic debris. Although excavators saved them and had some of them consolidated, they never found their way into the reconstruction of oecus 15 because there was no wall to hang them on. Since we know that the west wall of oecus 15 mirrored the decoration of the existing east wall, we flipped the image of the east wall and fit the new fragments into that scheme (fig. 7). Our work proceeded electronically from this point on, with Liddell proposing the positioning of the fragments in digital form. Queries in text boxes allowed team members to comment on the reconstruction directly. Images of fragments that have not found a home appear in the box at the lower right. Despite the redundancies between the two walls, several of the fragments open new avenues of research. The peopled frieze, executed in cinnabar red and belonging to a beam connecting two columns in the upper part of the wall, preserves more details than its twin on the east wall, and part of a tall rectangular shuttered painting invites comparison with the pendant-shuttered paintings resting on beams on the east wall. In addition to our work with physical fragments, we have had some success with digital reconstruction based on archival drawings and photographs. Shortly after its discovery in 1966, the painting in the north tympanum of cubiculum 11 faded drastically, with no record of its original appearance other than a schematic sketch (fig. 8). In the summer of 2008, two black-and-white photographs, shot in 1967, surfaced in the archives of the Superintendency of Pompeii (fig. 9). Martin Blazeby undertook the painstaking task of reconstructing the painting in color and inserting it into the Oplontis Project’s 3D Model of Villa A (fig. 10). It is a unique SecondStyle harborscape, the only preserved example of the use of a landscape to decorate a tympanum in the mature Second The Decorative Program of Villa A at Oplontis Style. Ivo van der Graaff ’s study of this image demonstrates the meanings that a fortified harbor might have conveyed to a contemporary viewer.2 What is more, integration of the tympanum painting with the other decorations, including the stuccoes and mosaic carpets, gives us a clearer picture of the ample repertory of architectural perspectives, figural motifs, and landscapes at the command of the painters of Boscoreale workshop—authors of at least two of the Second Style rooms in the Villa.3 As in cubiculum 11, in triclinium 14 it was a combination of archival photographs and drawings that allowed Blazeby to restore missing elements. A photograph shot in 1966 provides a sense of the chaotic situation the workers faced Fig. 10. Oplontis, Villa A, cubiculum 11, north alcove, tympanum (reconstruction Martin Blazeby). au: insert “the” here? Fig. 11. Oplontis, Villa A, oecus 15, east wall, with overturned portion showing west wall of triclinium 14, 1966 (SAP B1284). 9 John R. Clarke Fig. 12. Oplontis, Villa A, triclinium 14, west wall (reconstruction drawing, Ciro Iorio. SAP P1979). 10 (fig. 11). The lower portion of the east wall oecus 15 is still standing, so that one can recognize the image of the tragic mask and just the head of one of the famous Oplontis peacocks sitting on a ledge. But at the bottom of the photograph appears the image of a goddess in her circular shrine from the opposite side of this wall—a piece of the west wall of triclinium 14 overturned by the cataclysm. Fortunately, a conscientious draftsperson, Ciro Iorio, recorded these fragments before they were lost forever in the failed attempts to recompose them and reattach them to the reconstructed wall (fig. 12). Today the entire upper left quadrant depicted in Iorio’s drawing is lost, including the frieze decoration consisting of shields and armor, the ornate capital at the top of the large pier that runs from floor to frieze, as well as the imago clipeata to the left of the goddess in her circular shrine (fig. 13). Blazeby’s digital reconstruction recovers these features and—as is the case with cubiculum 11—it allows us to understand better how the decorative ensemble shifts from anteroom to dining area (fig. 14). Putting these digital reconstructions into a 3D model enhances their scholarly value, far surpassing the publication of reconstructions in traditional print media. Whereas the graphic conventions inherent in print publication prevent scholars from testing the effects of decorative schemes in a given space, in the digital model, a user can move, virtually, through the spaces to test the kinesthetic effects of the deco- The Decorative Program of Villa A at Oplontis rative ensemble. Furthermore, he or she can study the decorative ensembles, toggling between actual and reconstructed states and viewing them under varying light conditions. Finally, digital modeling allows changes and additions to hypothetical reconstructions that are impossible both with on-site, physical reconstruction as well as print publication. Fig. 13. Oplontis, Villa A, triclinium 14, west wall actual state (photo Paul Bardagjy). University of Texas at Austin [email protected] Fig. 14. Oplontis, Villa A, triclinium 14, west wall, restored (screenshot from 3D model). 11 John R. Clarke Notes See Clarke 1991, 47–49, nn. 33–35. Van der Graaff, forthcoming. 3 Clarke 2013, 2:204–8. 1 2 Works Cited Clarke, J.R. 1991. The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.–A.D. 250: Ritual, Space, and Decoration. Berkeley: University of California Press. ———. 2013. “Sketching and Scaling in the Second-Style Frescoes of Oplontis and Bosocreale.” In La villa romaine de Boscoreale, edited by A. Barbet and A. Verbanck-Piérard, 2:00– 00. Arles: Éditions Errance. van der Graaff, I. Forthcoming. “The Recovered Tympanum of Cubiculum 11 at Villa A (“of Poppaea”) Oplontis (Torre Annunziata, Italy): A New Document for the Study of City Walls.” In Oplontis Villa A (“of Poppaea”) at Torre Annunziata, Italy. Vol. 2, Decorative Ensembles: Paintings, Stucco, Pavements, Sculpture, edited by J.R. Clarke and N.K. Muntasser, 00–00. New York: ACLS Humanities E-Book Series. 12

© Copyright 2026