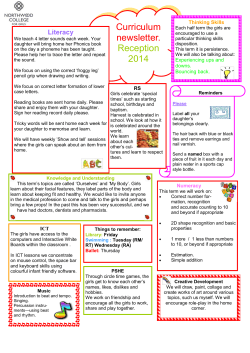

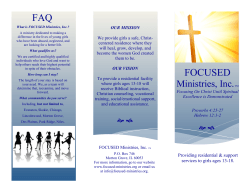

Community participation and after-school support to