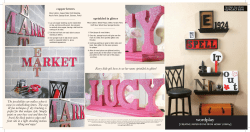

Labour & Leisure

Labour & Leisure Sir Jon Dai of the lane Mistress Margie of Glen More Stormhold Arts and Sciences Competition AS XLVI “Mystery Bag” At June Monthly Bash AS XLV, the Mystery Bags were distributed. Thank you to Honey of the Forest who picked up our bag containing: A piece of tan leather approx 30cm square; A piece of fabric which appeared to be linen, but had a synthetic component, approximately 60cm square; A piece of calico approximately 112cm square; A piece of cotton webbing approximately 1m x 25mm; A piece of cotton cord approximately 2m in length; A piece of bamboo approximately 1m in length and 6mm in diameter A piece of wood, complete with boring insects and ants, believed to be a fruitwood; A zip-lock bag containing star anise, pimento/allspice, nutmeg and cinnamon stick; A piece of pewter; A zip-lock bag containing somewhat felted raw wool; and The green “enviro” shopping bag in which it was all stored. Upon receipt of the bag and initial inspection our thoughts turned to what could be done with the contents. Initial thoughts with what could use the most bits and pieces, was to incorporate most of the items into a “Plague Doctor” costume and accoutrements. This would have consisted of the beak mask, hood, cape, pomander, stick and censer (thurible). Unfortunately although we could find references to plague doctors and their contracts and the above woodcut of an Elizabethan Physician, believed to be 16th Century, we could not find conclusive evidence for the classic plague doctor costume prior to 1665. This also uncovered a lot of information about other medical practices of the times but nothing that would use the mystery items. Following on from the mask idea, we then turned to the theme of ‘labour and leisure’. The Plague Doctor mask appears to be an extension of the leather masks used in the Italian Commedia Dell’Arte and is now more commonly known as the dottore della peste mask of Carnivale fame. In keeping with the doctor theme, we decided that we would undertake a leather commedia dell’arte mask for the stock character of Il Dottore. The cotton cord provided was used to make the ties for wearing the mask. Commedia dell’Arte also provided the stimulus for what may be done with the wood, linen and cotton webbing. Unfortunately the wood was too insect infested and damaged to cut a battacchio from, even though this was our original plan. The cotton webbing provided will form part of the handle and spacer required to make the clap. A battacchio is better known by modern audiences as a slapstick. Traditional Il Dottore props also include a linen handkerchief. The wool originally tempted us toward angling and the use of artificial baits, ie flies and lures. The bamboo and fabric reminded us of kites; most period references refer to these being made of paper or silk. The piece of pewter was well hidden in the wool and prompted us thinking about making a token for the Drakkar Sweep. Casting was the obvious choice and has led to research for the use of cuttlefish bone. Other award tokens were then considered, including the Gallant Drakkar, for which there is not a current token. As we are both neighbours rather than members of Stormhold, we could see the humour in creating a token for an award which is only given to those who are not members of the Barony. This left us with the calico, wood and spices. The wood was really only fit for burning, however all the pieces that came off (bark and borer residue), were rendered down to see if they could be used as a dyestuff. The bugs were identified. However, zoology and entomology are products of the 17th and 18th centuries. The burning of the wood prompted what we could do the rest of the items; making the wood into kindling, calico into char-cloth and a waterproof bag, and the spices into the makings for a mulled wine/spiced cider mix, or other period recipe. As a later addition we also decided to spin some somewhat felted raw fleece, and use it for knitting and making a drawstring cord for the waterproof bag. In keeping with our emerging theme of ‘Labour and Leisure’ we decided to use the calico to make a Bruegel style apron. Such an apron would have been made of linen, not cotton. Detail from the Bruegel painting “Children’s Games”. Any of our ‘Labour’ activities could incorporate the use of an apron. The green enviro bag will continue to be used in its initial role, to transport everything around and house the bits till needed! Decisions now made on what to do with our mystery items, experimentation and craft time begin. Labour and Leisure here we come! Commedia dell’Arte – Il Dottore Mask: Traditionally leather commedia masks are made on a wooden matrix. 1 Getting to the wooden matrix requires: A plaster negative to be cast from the players face and then press moulding clay into this cast. The characteristics of the mask are then further defined with clay and then this clay matrix is cut into pieces approximately 15mm wide. These pieces are then used to cut timber pieces that are laminated together, carved, trimmed and sanded to form the wooden matrix. As our wood working skills and equipment are limited, we decided to use a medium that would allow us to make a form. To this end we decided to use papier mache. We started with newsprint which had been soaked for three days, and then diluted PVA was added to the paper. Once the basic shape was formed, we used green tissue paper to further build the mold to the shape of the mask. This was then left to dry and then varnished to make a water resistant matrix over which wet leather can be placed and beaten into shape. The varnish used was 5 coats of high resistant polyurethane. The beating of the leather required a couple of specialist mallets, these were crafted using the piece of wood. Although damaged from the bug infestation (more ants were discovered during cutting) this provided enough timber for two mallets, and two smoothing tools. 1 http://www.isebastiani.com/Masks/MaskMaking.html The mask was then trimmed, stained and treated with a wax based leather sealer. Other features such as the eye brows and moustache were added. These were made from the provided raw fleece which had been scoured using urine to remove grease and dirt from the wool. Holes were punctured in the eyebrow ridge of the mask using an awl to allow the eyebrows to be sewn to the mask. The cotton cord from the mystery bag was used to make ties for the mask. These ties would probably have been made from leather thonging on original masks of the period. The eyebrows and moustache were trimmed to an appropriate shape. Commedia dell’Arte Props: Il Dottore traditionally carries a linen handkerchief. This was made using the fabric square which looked more like a linen, with a simple hand stitched rolled hem. As the original wood provided was too damaged to cut satisfactory pieces to construct the battocchio, we substituted a piece of pine lattice to make the clappers. These were shaped and sanded prior to the handle being bound with the cotton webbing. The webbing also provides the wedge that spaces the two halves of the battocchio in order to create the clapping effect. In keeping with the quality of the original wood provided, the wood we used was found behind the shed in Jon’s parents’ backyard. It was not purpose bought for the task. A battocchio of Antonio Fava’s, one of the few Italian masters of Commedia today, a depiction of Arlechinno with a battocchio, 1671, and ours. The Commedia dell’Arte was a theatre form which originated in Italy during the 15th Century. It was originally a form of street theatre performed by a single performer, in the character of a servant/menial, which developed to include two performers, often in a master/servant relationship. These two street performers often worked with a mountebank, hence the introduction of ‘the commercial break’ some 500 years ago. By the 16th century the popularity of this form of theatre had grown so that there were permanent troupes of professional actors who toured across Europe performing pieces that were largely improvised around simple scenarios rather than scripted. The most famous of these was probably the Gelosi.2 The Commedia dell’Arte troupe was comprised of actors who played stock characters/stereotypes. All characters, except the Amorati/Lovers wore half masks made of leather. The Amorati wore thick, stereotypical makeup which acted in much the same way as the masks of the other characters. 2 Commedia dell’Arte – An Actor’s Handbook John Rudlin, Routledge, London 1994 pp 8,9 The Book of St Albans, printed by the Schoolmaster Printer in 1496 contained The Treatise on Hawking, Hunting and Heraldry, as well as A Treatyse of Fyssynge with an Angle. The latter contains information on how to construct a fishing rod, horsehair line, flies and floats. It also instructs on different rigging methods for tackle depending on the angler’s target species. Utilising the dyestuff extracted from bark and wood debris: Some of the wool was dyed using natural dyes to match the description of the materials from A Treatyse of Fyssynge Wyth an Angle. Other natural colour fleeces were used as required; these included a black fleece and a mid brown/dun fleece. In this publication Dame Juliana Berners lists patterns for fly making by the month. Jon used these patterns to make flies as listed for the months from March to August. March April May June July August Jon also made a ‘peacock fly’. The appendix includes Jon’s adaptations for these patterns to construct his flies. Spices Because we would no longer use the spices as part of our ‘Plague Doctor’ plan, as a nosegay or pomander, we decided to use the spices – cinnamon, nutmeg, pimento/allspice and star anise – in creating food and beverages. Cinnamon and nutmeg were used in medieval cookery and they can be found in ingredients lists in many extant recipes. However pimento/allspice was a ‘New World’ spice which was brought back from the Caribbean to Spain by Columbus. Columbus, realising the value of pepper, brought this spice back having incorrectly identified it as pepper. (Not surprising really as Jon and I initially made this mistake too.) The word ‘pimento’ means pepper in Spanish. The more common name of ‘allspice’ came into common use in the 17th century. Star Anise is native to China and Vietnam and was not introduced into Europe till the 17th Century, hence we cannot find medieval recipes with star anise listed as an ingredient. However, a very similar flavour comes from anise. “Anise has been cultivated in Egypt for at least 4,000 years. A reference was found in an Egyptian papyrus dating around 2000 BCE. Pharaonic medical texts indicate that the seeds were used as a diuretic, to treat digestive problems, and to relieve toothache. Anise is mentioned in the works of Hammurabi. Hippocrates recommended it to clear the respiratory system. Dioscorides listed it as a medicinal plant and wrote, in the 1st century CE, that anise "warms, dries, and dissolves". Although mainly used in food, its licorice flavour has been used medicinally as a treatment for abdominal upsets and intestinal gas, as well as for a breath freshener. William Turner recorded in 1551 that "anyse maketh the breth sweter and swageth payne". Although rooted historically in the Mediterranean area, it is widely available in South America. Spanish colonists brought it to the New World in the 16th century. Its fragrance was said to have been as valuable as a perfume. In medieval times, anise was used as a gargle with honey and vinegar to treat tonsillitis. Pliny recommended chewing it upon awakening to get rid of "morning breath", but he also advised keeping it near the bed to stave off bad dreams. The Romans used it as a form of currency; and Hippocrates used it to treat coughs, as did the healers before him. In the 16th century, Europeans discovered mice were attracted to anise and baited their traps with it.”3 The similarity of star anise to anise means that it is not anathema to substitute one for the other in medieval recipes. After a great deal of research and perusing medieval recipes and their more modern redactions we decided to use our mystery spices in 3 culinary items. All spices were crushed and used in a crushed or ground form in our recipes. 3 http://www.innvista.com/health/herbs/anise.htm Spiced apple juice for which we used a PotusYpocras recipe from Gode Cokery, 14th century England, as the inspiration.4 We decided to make spiced apple juice for two reasons: non alcoholic so anyone can drink/taste and can be consumed pretty much straight away and does not require storage time as Ypocras does. We have made 2 variants of the spiced apple juice. Both were strained through cloth 4 times after sitting for about 36 hours. We could not use either of the fabrics provided as the weave of both the calico and the synthetic blend was too close to be an effective strainer. Recipe 1: 750 ml commercial apple juice, 1 tablespoon cinnamon, 1 tablespoon nutmeg, 1 tablespoon star anise, ½ tablespoon ginger, 1 tablespoon cloves, 1 tablespoon white pepper. Recipe 2: 750 ml commercial apple juice, 1 teaspoon cinnamon, 1 teaspoon nutmeg, 1 teaspoon allspice, 1 teaspoon star anise. Unlike Ypocras recipes we did not add sugar as apple juice is already extremely sweet. They could be drunk cold or warmed. The spice ingredients were also used in a fried ‘rissole’ recipe and a baked pie recipe.5 Rissoles au Common from Menagier de Paris, 14th century, is a sweet dish of fruit and spices wrapped in pastry and fried. There are a number of references to such dishes supplied in our research and resources appendix. We worked from the original references and also from a redaction. However we did make some further changes to the recipe as well. RISSOLES AU COMMON Margie’s Redaction Resources: Menagier de Paris 1393 - Rissoles.Redaction by Jacques Bouchut (internet Maitre Chiquart) Ingredients: (20 rissoles) Dough: 4 See appendix on spices and recipes. Ibid 55 ½ kg flour 100g butter 1 egg ~200 ml water to mix Make dough and rest for at least 1 hour – up to 3 hours – in a cool place, covered with a towel. Filling: 2 large apples, I used Pink Lady 15 or 16 soft dried figs 60g raisins 50 g walnuts ¼ - 1/2 tsp star anise ¼ tsp pimento/allspice ½ tsp ginger ½ tsp cinnamon ¼ tsp nutmeg Cook grated apples with a little water. Add chopped figs and raisins, and continue to cook. Add chopped nuts and spices. Mix well. Roll dough very finely. Cut strips 7cm wide. Cut each strip into 8cm rectangles. Place small spoonful of filling on each rectangle and press the moistened edges together around the filling. Fry in hot oil until golden. Drain on paper towel and dust lightly with icing sugar. Feedback is provided, though have to say Anora’s is the favourite – “Leave the plate here please!” The fruit and meat pies I made were inspired by medieval recipes such as Lombard Pasties, 14th century, and Pies of Parys, 15th century. I did not use an extant recipe but made up my own based on the recipes above. Fruit and meat pies Redaction by Margie of Glen More Ingredients: 1 large apple grated 300g minced beef ½ onion, finely diced 1 jar fruit mince (but could make own) Cinnamon Nutmeg Pimento Pepper (Spices were added to taste, about a teaspoon of each.) Brown meat and onion. Add apple and cook till soft. Stir through fruit mince and add spices and pepper to taste. Remove from heat. Pastry: 500g flour 200g butter Rub butter into flour. Add water as necessary to form dough. Let stand at least one hour. Roll dough out thinly. Line muffin tins. Place dessertspoon of mixture into each. Top with pastry circles and seal. Glaze with beaten egg if desired. (Makes 2 dozen.) (NB this could also be made as one large pie rather than individual ones.) Cook at 180oC for 20 mins. (The fruit mince I used was “Socomin” brand and contained currants, sultanas, apple, citrus peel and undisclosed spices.) We made some of these pies in a patty cake tray rather than muffin tray and these were very popular as they were more bite sized. Feedback is provided. Fleece: The fleece was rather dirty and slightly felted. It looked very familiar to me and I surmised that it may have come from Master William Cumyn’s sister as I have a couple of fleeces from her in a very similar state. Hence I decided that we had plenty of fleece so could use it for a number of things. It was used for spinning and then knitting the rough peasant style fingerless mittens and also for making a drawstring cord. Some fleece was dyed and then used for making the fishing flies, together with some natural coloured fleeces as required. Fleece was also used to make the eyebrows and the moustache on the Il Dottore mask. We decided that before we did anything else we should try to clean the fleece that came in the mystery bag and I also cleaned enough fleece for dyeing. The scouring of the fleece to remove grease and other impurities was done with urine. The fleece was put into a snap lock bag and covered with urine and then put into a damp place for the ammonia to develop. It was left for three days and then removed and rinsed. ” Human urine was used for scouring and cleaning wool and for dying wool, where it was used as a mordant. The woollen cloth industry had to compete in certain areas for supplies of urine with the alum and the saltpetre industries. Urine provides a very convenient and accessible source of alkali in the form of ammonia, which is produced as the urine becomes stale and the urea, within the urine, decomposes to ammonia. This ammonia was useful for cleaning wool, prior to spinning as well as fulling. In many wool-processing areas, a urine collection was set up in urban areas to collect the 'chamberlye', 'wash' or 'lant'; large quantities were even collected in London and sent up north by ship.”6 The urine did an excellent job of cleansing the wool. Scoured wool on left, untreated on right. Except for the blue dye all dyes were natural plant based dyes. From top right: madder, eucalypt leaves with copper after mordant, eucalypt leaves, brown onion skins, bark of the ‘mystery’ wood which we believe was a fruit tree. 6 Isle of Wight Industrial Archaeological Society report The Treatysse on Fyssynge with an Angle gives information on what colours will be needed to make the flies, and what materials to use to make the dyes.7 The wool is used to form the bodies of the flies. The scoured but undyed fleece was sewn into the leather commedia mask. Moustache sewn in, making holes for sewing in eyebrows. The fleece that was spun was not scoured prior to spinning, it was ‘spun in the grease’. It was deliberately coarsely and roughly spun. For fine treatment of such fleece it would have been carded and combed prior to spinning. Our aim was to make a very rough yarn that could be used to knit gloves suitable for manual labour that would be both protective and warm. Labourers apple picking Luttrell Psalter 14th C. Although initially the aim was to make a pair of men’s gloves, as during medieval times it is men you see in artists’ depictions wearing gloves to do manual labour, it soon became apparent that it would be unlikely that they would ever be worn. Therefore one man’s sized glove was made and then a small pair were knitted knowing that they would be used. 7 See appendix. I used a spinning wheel with a flywheel such as was used after 15th century in Europe. The yarn was Z spun and S plied. It was then skeined and washed, then rolled into balls prior to knitting. Knitting was done on 4 needles as was common practice prior to 17th century. This yarn was also used to make the drawstring for the waxed pouch. Tinderbox: The piece of wood in our mystery box inspired many creative ideas however it was really only fit for one thing – burning! It was infested with ~50 dome-backed spiny ants (Polyrhachis australis) and two different types of borer; the round headed wood borer (coptocercus rubripes) and a very small but much nastier variety that I can’t find where I put the name for. And no, we didn’t make anything out of our mystery insects! Did kill and preserve the round headed wood borer but seems Ry threw him out. So insects gone, we moved on to how and why to burn our wood. Our piece of bamboo was also damaged about half way down so could not be used as a full length, so it seemed that burning at least some of this might be a good idea too. OK, so if we were going to start a fire we would need a flint and steel, and tinder. We had mystery fabric so making charcloth was our next endeavour. One of the mystery fabrics was a synthetic/cotton so was unsuitable for turning into charcloth as it melted. We found that both cotton and linen would turn into charcloth well but cotton performed better when used with flint and steel to start fire. We also did the same treatment to some non woven fibre which we believe to be cotton/kapok. Of the fabrics we tried the soft, open weave cotton provided by the ADF to clean their firearms was by far superior as charcloth. Our first effort was done outside using linen and the BBQ. We did not leave it on the heat long enough and the linen was only scorched rather than charred. Further experiments were done straight over the naked flame of a gas burner of domestic cooktop. This was much more successful. Our mystery wood and excess bamboo was reduced to kindling and shavings. A steel was made from an old file, and quartz was used as flint. And one spark will light the best of the charcloth, and voila – Fire! Left:Firestrikers. Right:our tinderbox. We also used a piece of the mystery calico to make a waxed drawstring bag to hold our tinder box and keep it dry. It was treated with a mix of beeswax and linseed oil, and hand sewn using double running stitch for extra strength. Beeswax has been used as waterproofing agent since pre history and linseed oil is hydrophobic; it repels water. Linseed oil is made from flax seeds, from the same plant used to make linen. During medieval era charcloth would have been made over an open flame/fire, and would have predominantly been linen or hemp. This is why we were disappointed when our linen did not work as well as the cotton charcloth. Casting/Pewter: It was not till well after we had started that we remembered the chunk of pewter hiding in the zip- lock bag. We very quickly decided that making a prototype for a Stormhold token would be our aim as you often hear about groups being short of tokens to give out in court. So token for what? Bit of research into which Stormhold awards did not have tokens. We looked at the Drakkar Sweep and then the Gallant Drakkar. Years ago the token for the Gallant Drakkar was a simple button and we were fairly sure there was not a current token. There was also some irony in us making an award token for those who do not reside in the Barony. So from there we looked for images that might be appropriate. It seemed appropriate to have something to do with a drakkar on the token, so we looked at whole images of drakkars and also images of prows. For ease of construction we did not go with our favoured idea which was to make an annular brooch with ends resembling a drakkar prow and stern. We thought of using the following image and tightening it into more of a circle and adding a pin. Rather we went with a drakkar which is symmetrical and seems to have a prow on both ends, like it is both coming and going. Seemed appropriate for a token given to non Stormholders. We cast two different designs. One was a copy of a drakkar pendant that I have had since about 1973 and the other was based on an extant piece, and is a drakkar which is symmetrical and seems to have a prow on both ends, like it is both coming and going; seemed appropriate for a token given to non Stormholders. This bronze brooch was designed as a stylized drakkar, dragon heads on the prows and shields along the side. It belongs to the Danish National Museum in Copenhagen, and was discovered at Lillevang on the Island of Bornholm in Denmark. Once a design was chosen we needed to find a simple method of pewter casting, and although we looked into sand casting and lost wax we decided to experiment with cuttlefish casting to see if we could get a decent cast from it. We bought cuttlefish from the local pet supply shop. This was cut with a fine hacksaw and then sanded to achieve a flat surface. Because we already had the designs we wanted to cast these were simply pressed into the cuttlefish. We made the mistake the first time of trying to get a more 3 dimensional cast by pressing into both front and back pieces of cuttlefish. This was not terribly successful due to difficulty of lining up the front and back of the cast. After that we focused on pressing the shape into one of the sides of the cuttlefish. The details were enhanced by further carving of the cuttlefish prior to pouring the pewter. We also experimented with having the sprue (for pouring) on the top of the casting and then below which worked better. We also successfully cast two tokens at a time. Cuttlefish bone is the internal shell of Sepia officinalis This mollusc is appreciated in Mediterranean cuisine. There is evidence of cuttlefish casting being used during medieval times. It leaves distinctive marks on the reverse of the casting. You can see these marks on the backs of our castings. In Baden- Württemberg, Germany, two belt buckles dating from the VI or VII century have been found, showing these dinstinctive marks left by the cuttlebone. In extant shopping lists of goldsmiths' workshops in Florence and Venice, at the beginning of the Renaissance, there is evidence that sums were reserved to purchase cuttlefish bones. The cuttlebone gives off a rather masty, fishy smell especially if it burns during the pouring process. However, this in no way affects the casting. After casting the tokens were cleaned up with a fine hacksaw and then with files. A dremel was also used on the double prowed drakkars. To melt the pewter we used a small coffee pot on a gas stove top and also a small spirit stove that took somewhat longer to melt the pewter. Pewter melts at 300oC so is a very easy metal to work with. During the medieval era cast pewter was used for pilgrim tokens, jewellery, and dress accessories like buttons and belt fittings. These are pewter pilgrim tokens from medieval pilgrims who visited the shrine of Thomas A’Beckett at Canterbury Cathedral. Bamboo: Well what do we do with that? Nothing from Medieval Europe we think. Bamboo species are found from cold mountains to hot tropical regions. They occur across East Asia, through to Northern Australia, and west to India and the Himalayas. They also occur in sub-Saharan Africa, and in the Americas from the Mid-Atlantic United States, south to Argentina. Continental Europe is not known to have any native species of bamboo, though they had seen kites which had been brought back to Europe by travellers such as Marco Polo. Medieval banner kites. Kites! India and China. Traditional Indian fighter kite (modern materials) NB we used balsa for this kite as could not find a suitable piece of bamboo with enough length. We used two pieces of bamboo for the cross span to balance the unevenness of the bamboo. But our bamboo is broken...we can find more. Fortunately only a kilometre away from home on Margie’s walking track is a substantial stand of bamboo. So load up Jon’s truck and we have heaps to work with. The problem we found was finding any bits of consistent diameter as the nature of it as a grass is that it gets thinner as it get towards the top. (And another problems with it; it makes the cats throw up if they chew on the leaves when you leave it lying in the lounge room.) The original piece of bamboo was used for a strut on one of the kites and also in the construction of a spool for the kite line. This spool also utilised end discs made from the ‘mystery’ wood. The bamboo that we couldn’t use has been added to our store of materials for burning. Our kites are constructed predominantly from bamboo and tissue paper – rice paper or silk would have been more common pre 1600. We used PVA glue rather than an animal sinew glue which would have been used historically. We have made a traditional Chinese kite, see picture above, and ancient Chinese kite – the flat square one, and an Indian Fighter kite though the line has not been treated with ground glass to slice through an opponent’s kite string. In 478 BC it was recorded that a Chinese Philosopher, Mo Zi, spent 3 years making a hawk from wood which flew. Was this a kite? Early Chinese kites were made from bamboo and silk, but later on paper was also used. “In 200 BC a Chinese General Han Hsin used a kite to fly over a castle he was besieging then used the length of the kite line to ascertain how far he had to tunnel so that he could successfully enter the fortress. Another General under siege used kites with harps fitted to them and at night flew them over the enemy camp. He sent spies into the camp and when the kites started making a wailing noise the rumour was spread around that the Gods were warning them of a great defeat the next day and consequently the enemy fled in terror. In the 13th century Marco Polo wrote about how the shipping merchants tied someone (usually a drunk) to a huge kite and launched the kite with the drunk attached before the ship set sail. If the kite went high and straight it meant a quick and prosperous voyage but if it crashed or didn’t fly well it was a bad omen which meant no-one set sail.”8 (The name for kite in China is FEN ZHENG, fen is wind and zheng is a stringed musical instrument.) 8 http://www.kiteman.co.uk/CHINESE%20KITE%20HISTORY.htm Don ypron clene and gloves warme. Tak olde logge and chop hym yp fyne. Strike flynt with steele and let light charclothe and tynder. Mak yp wele. Cast kyndlyng ynto fyre. Scour wolle in yrine stronge and dye divers hues in olde vats overe fyre. Of other wolle spyn and mak cordes and knytte. Melte mettle over gode hete and poure hym forth to mak things of joye. Mak mask by hyttinge lether with mallets of wode and waxe hym wel. Fyx wolle on visage. Bind divers wolle and fethers onto hookes of yron with sylke for to catch fysh with an angle. Ypon the fyr, warme the cyder and fry rissoles so that they be gode to ete. Whenne sated cast a kyte into the skye for plesure, or caste flys to catch fysse. To watch commedia is to gretely revel and to lighten the soule.

© Copyright 2026