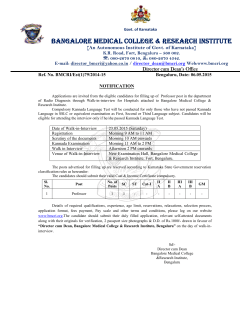

Miscellaneous