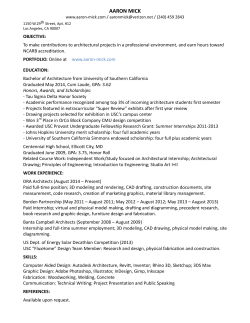

Historical Dictionary of Architecture