For the Birds: Backyard Hens + Forkli Materials =... By Elizabeth McGowan

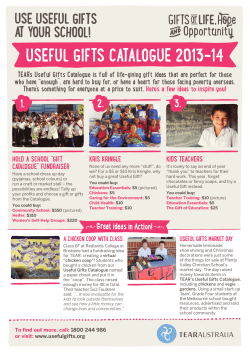

For the Birds: Backyard Hens + Forkli Materials = “Eggs‐cellent” Results that he jokes about having musical a en on deficit disorder. Covert, who grew up in Takoma Park, graduated from art school with a degree in metalsmithing. She’s now studying for cer fica on as a health coach. By Elizabeth McGowan Back in mid‐December, Nathan Graham and Natala Covert feared a certain speckled Sussex hen would put the kibosh on the agricultural enterprise they had hatched for their Mount Rainier back yard. Yes, they both are fond of the eggs that the hens provide. But it’s about more than just cul va ng a backyard food source. There’s a certain beauty to the whole reuse cycle. The hens supplement their diet of organic pellets and scratched‐up bugs with kitchen scraps and spent grain from DC Brau, where Graham’s younger brother is the brewmaster. The coop’s soiled pine shavings are composted and then recycled in the adjacent vegetable garden. Plus, Graham and Covert admire the birds’ tenacity as well as the grace and coordina on they display while balancing upon the s cks they sleep on at night. The suspect chicken was evidently the diva of the quartet of hens adap ng to their new life in the couple’s Community Forkli ‐inspired coop. Alarmingly, she felt compelled to regularly serenade the neighbors. “She was always singing,” Covert said. “And we thought, oh no, everyone in the neighborhood will hear her. We’d told everybody we wouldn’t be ge ng a rooster, so we didn’t want this to be a nuisance.” Graham said their neighbors almost like it when he and Covert leave town for a few days because they know they will be “paid” in eggs for watching the hens. Natala Covert and Nathan Graham sketched a series of coop possibili es before tackling the actual construc on in their Mount Rainier, Md., garage. Over in rural western Howard County, Ryan and Tabatha Cooper totally understand how mesmerizing chickens can be. The two 28‐year‐olds some mes relax on their one‐acre Mount Airy lot by propping lawn chairs near their handmade coop and sipping wine. “I happen to like pets that live outside,” said Kennedy, who has experience with small‐scale chicken farming. “Some people are cat people, some people are dog people and some people are chicken people.” Community Forkli certainly champions those chicken people. Miss Franklin, le , earned her name because of her robust set of pipes. Here, she shares space in the coop with The Machine, who cranks out eggs as if she’s automated. The roos ng area behind the li le latched door to the le is where the chickens lay their eggs. Fortunately, the neighbors became enamored with the fowl’s powerful, persistent yet pleasing set of pipes. “They made a point of telling us that they enjoy hearing the sounds of the farm in Mount Rainier,” Graham interjected. Naming the speckled Sussex soloist, of course, was a no‐brainer. She was christened Miss Franklin as a tribute to the soulful Aretha. And she is evidently content to have set up housekeeping with her sister hens—a golden comet called Goldilocks for obvious reasons and a white leghorn named The Machine for her assembly‐line like egg produc on—in suburban Washington, D.C. The fourth hen was the unfortunate vic m of a run‐in with the family dog several months ago. Small‐scale, urban backyard chicken farming is all the rage in metropolitan regions na onwide but it’s a bit of a dicey proposi on in Mount Rainier and other developed parts of Prince George’s County where zoning regula ons are somewhat ambiguous and contradictory. Graham, 28, and Covert, 25, are among those who want the Prince George’s Council to follow the lead of a report on urban agriculture issued by the Maryland‐Na onal Capital Park and Planning Commission last fall. It specifically recommends that the county legalize small flocks of hens as a trigger to spur mini‐farms in its ci es. Brentwood resident Bradley Kennedy has carefully tracked the ins and outs of backyard chicken farming since 2010 when she helped to spearhead a pe on drive as a representa ve of an advocacy group called Prince George’s Hens (www.pghens.com). The organiza on has collected at least 1,000 signatures since the summer of 2010 from locals in favor of allowing county residents in single‐family homes to rise up to half a dozen hens. But Kennedy and her cohorts are s ll wai ng for a council member to sponsor legisla on at the county level so chicken farming can gain momentum instead of being a slightly stealth opera on. Prince George’s Hens makes it clear that cock‐a‐doodle‐doing roosters would not be part of the mix. One, roosters are too loud to mingle in residen al neighborhoods. And two, the males are only necessary for farmers needing more chickens. Hobbyists such as Graham and Covert want to harvest only eggs. For starters, the 34,000‐square foot warehouse offers the mother lode of materials for chicken coop constructors. Plus, the Forkli wrote a le er in early April encouraging the Prince George’s Council to allow homeowners in all residen al zones to keep small flocks of chickens because “the resurgence of backyard hen‐ raising across the na on is partly driven by the same “green” and cost‐conscious values that Community Forkli serves.” Indeed, Graham and Covert were mo vated to try hen tending a er visi ng like‐ minded friends in Portland, Ore., last summer. Covert’s mother, a local jewelry maker and sculptor, had introduced her daughter to the wonders of Community Forkli several years ago. So the Edmonston treasure trove was top of mind for the duo when they rented their Mount Rainier bungalow last October and received approval from their landlord to begin scheming their coop. They knew the dimensions they wanted for the roost box and “a c” perches because Covert had studied organic chicken farms while traveling in Europe. A er sketching a series of rough blueprints, they trekked to the Forkli to si through the goodies. Once they uncovered a bundle of 1‐inch by 6‐inch boards that were the perfect length, they knew they’d hit the jackpot. They also found ordinary plywood for the walls, cork‐covered plywood for the roof, beadboard for the interior, carpet squares for insula on and a large hinge for the li le latched door to the roost where the eggs are collected. A Forkli wood‐frame window—opened via a repurposed drawer pull—was transformed into the door the chickens use to access their ramp to ground level. “We found things we could use and then we made them work,” Graham said, adding that plas c roofing, chicken wire and hardware odds and ends were all they needed to buy elsewhere. “It’s a fun place with cool folks. You just feel crea ve when you walk into the Forkli . I see things and think, ‘What can I turn that into?’ Both Graham and Covert work evenings in the restaurant business, so they tag‐ teamed the coop construc on in their garage during their free daylight hours. What emerged Dec. 2 was a sturdy, spacious and func onal 5‐foot by 10‐foot structure that’s 6 feet high featuring a roost box, a ramp and s cks in the “a c” that serve as perches at night. The main door and an interior trap door both open into an airy, wire‐enclosed “English basement” that serves as a refuge from predators and a place with easy access to the dust that chickens cherish because it protects them from sun exposure and mites. Lawn chairs, glasses of wine and backyard chickens are all Ryan and Tabatha Cooper need to relax at their Mount Airy, Md., home. They built the coop with Community Forkli materials. “Chickens are fascina ng to watch, even if they’re just scratching around during supervised play me when we let them out,” said Ryan, a hor culturist and plant scien st employed on the University of Maryland’s Rockville campus. “They’re not loud and they’re not dirty. And the fer lizer they produce is great. We save that for our garden.” With a surname such as Cooper, it would seem poultry would be Ryan’s des ny. But he hadn’t envisioned hens as part of his future un l Tabatha, a dairy ca le gene cist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, enrolled them in a chicken‐ keeping course several months ago. A erward, they received clearance from their landlord and neighbors before checking out resources such as backyardchickens.com for coop designs. “That’s when Community Forkli popped into my head,” said Ryan, a talented woodworker and metal fabricator. “Rather than make a long drive and pay retail prices at Home Depot, I figured we could make a longer drive and spend less money.” At the Forkli , they scored some lumber, a window and handfuls of hardware. Two of their favorite finds were a piece of Corian countertop and a metal‐clad door. Ryan cra ed the countertop into a small pop‐up door that operates on a rope pulley system so the hens have access to their enclosed run. The metal door is the coop entrance and exit. Both doors are heavy and slick enough to keep predators at bay. “I was kind of making it up as I went along,” he said, adding that the 12‐foot by 6 ½ ‐foot structure that is 7 ½ feet high at its peak was 97 percent complete when their 11 chicks arrived in early April. “I hear lots of conversa ons where people are worried about what color they should paint their coop’s interior. Believe me, as long as the chickens are warm enough in winter, cool enough in summer, well fed and safe from predators, they don’t care about paint.” He and Tabatha are in the midst of planning a coop‐warming party for late May. Whether raising chickens in Mount Rainier or Mount Airy, these hen aficionados say there’s no down side to caring for their feathered friends. They are elated to have “pets” that provide protein for their breakfasts, lunches and dinners – and even the desserts they bake. Not only do the eggs taste be er, their excep onally orange yolks just look more appealing in the skillet. “Every other major metropolitan area in the country allows backyard chickens,” Kennedy noted. “We’re a li le behind the curve. This would be an opportunity for Prince George’s County to take the lead.” She pointed out that chickens are representa ve of the modern green sustainable movement because not only are their eggs a local food source, but they also provide natural pest control, eat food scraps and are an bio c‐free. Oh wait, there might be just one ny drawback. “I just wish,” Covert concluded a bit wis ully as she cracked a few eggs into a bowl of chocolate chip cookie dough, “that the hens would be willing to cuddle a li le bit more.” Natala Covert and Nathan Graham have access to some of the freshest eggs in Mt Rainier. Despite the coop’s urban se ng, crows s ll sound their dis nc ve warning when hawks and other threats approach, promp ng the chickens to scurry to safety in the coop or behind the wire fencing. “Going to the Forkli gives you something to do and a erward you feel good about what you did with what you bought there,” Graham said. “The corpora ons of the world are racking up money. We understand there’s a place for that but we’re just not into it. They don’t need our money. We’re trying to be as self‐ sustaining as possible.” Natala Covert, holding Miss Franklin, and Nathan Graham, holding The Machine, show off the eggs the hens made and the coop they built in their Mount Rainier back yard. Graham, a na ve of Maryland’s Calvert County, earned a degree in economics and classical music. He’s content with his decision to morph from a cubicle‐bound professional to a free‐ranging drummer and banjo player whose taste is so eclec c A rich orange yolk and the transparent membrane under it are a sign that an egg is ultra‐fresh. Here, Nathan Graham fries one he collected just a few hours beforehand.

© Copyright 2026