View PDF - Cincinnati History Library and Archives

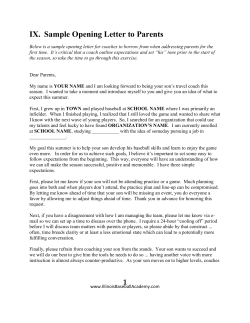

Baseball's Immortal Red Stockings by LEE ALLEN The origin of baseball as an amateur endeavor is shrouded in doubt. It was, originally, a game for boys, and grew up without printed rules or documentary evidence of any kind as to its earliest days. But the origin of professional baseball is undisputed: The first entirely professional team was supplied by the Cincinnati Red Stockings of 1869, a club that played from Maine to California wherever opposition could be found. The Red Stockings engaged in sixty-five games without once losing, traveled nearly twelve thousand miles by rail and boat, appeared before more than two hundred thousand spectators, and scored 2,395 runs to 575 for their opponents. The importance of the Red Stockings to baseball history does not lie in their extraordinary achievement on the field, impressive though that was. Their contribution consisted of establishing the fact that baseball could succeed on a professional basis. They drew so much attention to the game that clubs began to spring up in their wake as indiscriminately as dandelions. These clubs grew so strong that by 1871 they were able to form baseball's first major league, The National Association of Professional Baseball Players, forerunner of the National League of which Cincinnati is still a member. The first baseball club of any kind was organized in Cincinnati in 1860 by Matthew M. Yorston, a resident of the city. He made by hand the baseballs that were used, and the team played informally at various sites in the downtown area: at the foot of Eighth Street, near the present location of the Crane & Breed Manufacturing Company; at the Orphan Asylum lot on Elm Street, where Music Hall now stands; on the old potter's field that is now Lincoln Park; and eventually in the Millcreek bottoms, where the Red Stockings were at home and where the Union Terminal was later built. As an amateur team, the Red Stockings were formed on July 23, 1866, at the law offices of Tilden, Sherman & Moulton, in the old Selves Building, 17}^ West Third Street. The original members included some of the most prominent citizens of the city. 192 The Bulletin Among them were Alfred T. Goshorn, Aaron B. Champion, Henry Glassford, William Tilden, J. William Johnson, and George B. Ellard. Baseball at the time supplied activity for gentlemen at leisure, and among the Cincinnatians interested enough in the sport to participate were Bellamy Storer, Drausin Wulsin, Stanley Matthews, J. Wayne Neff, John R. McLean, and Andrew Hickenlooper. There was no thought of professionalism, at least until August 1865, when William Henry (Harry) Wright, a native of England and resident of New York, was brought to Cincinnati at a salary of $1,200 a year to serve as bowler for the Union Cricket Club, which had been in existence since 1856. Wright was more interested in baseball, however, than cricket. In 1867 the Red Stockings leased the Union Cricket Club's grounds, and many of the cricket players became members of the baseball team, an event that gave the comparatively new game greater emphasis. Attendance increased rapidly at the baseball games, and Wright became the leader of the movement to form a professional team. This was the natural outgrowth of the desire for victory. The lower classes supplied the best players, and these athletes were principally interested in money, an attitude that is not difficult to understand. But the decision to turn professional was not received enthusiastically in all quarters. One of the early amateur players, George A. Wiltsee, later in life explained the point of view. In 1916, in a conversation with William A. Phelon, baseball writer for the Cincinnati Times-Star, he said: Professional ballplayers were under a social ban, and the amateurs were not supposed to associate with them or even recognize them off the field - the only conversation between the two classes was on the diamond, and limited to subjects of the game. When the great Eastern players who composed the majority of the Reds were imported to Cincinnati, a trick was resorted to - a trick which has been copied at many a college and by many a semi-professional or alleged amateur ball club in more modern days. All these professionals were given jobs in the business houses of the team's backers jobs where they reported every morning, were visible to callers or doubtful skeptics, and drew small salaries, although few of them ever did a stroke of work. In this manner, the gap between amateur and professional was bridged; the Reds became, nominally, local businessmen who didn't have to play RED STOCKINGS OF 1869 — From Harper's Weekly, July 3, 1869 Baseball's Immortal Red Stockings 193 194 The Bulletin ball for a living and, slowly, month by month, the barrier between 'gentlemen' and 'professionals' was broken down. The team assembled as the Red Stockings of 1869 was as follows: PLAYER AGE Harry Wright Asa Brainard Douglas Allison Charles H. Gould Charles J. Sweasy Fred A. Waterman George Wright Andrew J. Leonard Calvin A. McVey Richard Hurley "OCCUPATION" Jeweler Insurance Marble cutter Bookkeeper Hatter Insurance Engraver Hatter Piano maker None 35 25 22 21 21 23 22 23 20 20 POSITION Center field Pitcher Catcher First base Second base Third base Shortstop Left field Right field Substitute SALA $1,200 $1,100 $ 800 $ 800 $ 800 $1,000 $1,400 $ 800 $ 600 $ 600 It is interesting to observe that Gould was the only player on the squad who was a native Cincinnatian. Leonard and Sweasy were residents of Newark, New Jersey; George Wright, Waterman, and Brainard came from New York City; Allison from Philadelphia, New Jersey, and McVey from Indianapolis, Indiana. George Wright, a brother of Harry, was the first acquisition. He was such a celebrated shortstop that small boys used to say, "I'd rather be Wright (George) than President." The pitcher, Brainard, was next obtained, and it was then believed imperative to find a catcher who could hold him. Colonel John P. Joyce, secretary of the club, and Alfred T. Goshorn went East to find one, and stopped first at the Continental Hotel in Philadelphia. Goshorn was not feeling well and remained in his room, but Joyce went out for a walk. He ended up in the suburb of Manyunk, and perched on a fence to watch a sandlot game. Doug Allison was catching, and Joyce's first impression was that he was ungainly. But at bat Allison suddenly began to move with grace and hit a long home run to center field. After the game, Joyce introduced himself to Allison and took him on a carriage back to the Continental. Telling Doug to wait, he rushed up to Goshorn's room and said, "Goshorn, I've got him." They both went to the street, and Allison was found sitting there in the carriage, a tanned and freckled country boy whose boots and clothes were covered with brickyard clay. On his head was a twenty-five cent straw hat with half the rim gone. Joyce and Goshorn bought him a suit, made him get a haircut, and took him on the train back to Cincinnati. Baseball's Immortal Red Stockings 195 It seems singularly appropriate that this great, undefeated team should have had as its president a man named Aaron Burt Champion, a gentleman of real distinction and a man who devoted his life to public service. Born at Columbus, Ohio, on February 9, 1842, he attended Antioch College when the famed educator, Horace Mann, was president of that institution. He became an attorney and began to practice in Cincinnati in 1863. In 1872 he was a delegate from the second Ohio district to the national convention at Baltimore which nominated Horace Greeley for the presidency. As attorney for the ThompsonHouston Electric Company, he was considered to be the most knowledgeable man on electrical matters of any attorney in the western country. He was also active as a trustee for Antioch and president of the board of the House of Refuge. It was during the presidency of Champion that the Red Stockings adopted the uniform that became their trademark and still survives. Baseball players originally wore cricket uniforms, but at the suggestion of George Ellard an order was placed with a Mrs. Bertha Bertram, who conducted a tailor shop on Elm Street, near Elder, for short, white flannel trousers, white flannel shirt, and the famed red stockings. When the pitcher, Asa Brainard, came to Cincinnati, he boarded at the home of a family named Truman, a once wealthy clan whose male members had been associated with Truman & Wilson, the firm that came to be known as Wilson, Hinkle & Company; Van Antwerp, Bragg & Company; and eventually the American Book Company. (This firm was engaged in publishing, one of its publications being the McGuffey readers.) But somehow the Trumans became impoverished and had to take in boarders, one of whom was Brainard. Almost immediately after moving in with the family, he became ill of smallpox. He was nursed back to health by Mary Truman and her sister, Margaret. When Asa recovered, he and Mary became married. Mary and Margaret Truman, by this time enthusiastic followers of baseball, began sewing red stockings to supplement those supplied by Bertha Bertram. The season of 1869 opened on April 17, with the Red Stockings defeating a picked nine of local players, 24 to 15. After handily winning several other games, the team set out on its first road trip, accompanied by Harry M. Millar, a writer on the old 196 The Bulletin Commercial. The first sports writer to travel with a professional baseball club, Millar also served the team as scorer; his scorebook is preserved today in the Albert G. Spalding collection of baseball literature in the New York Public Library. The first stop was at Yellow Springs, where Antioch College was defeated. The team then rolled on to Mansfield, Cleveland, Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, Albany, Troy, Boston, New Haven, and Brooklyn, routing the opposition in all those communities by decisive scores. The first real test came in Brooklyn on June 15 when the Red Stockings struggled against the Mutuals of New York and barely defeated them, 4 to 2, an unprecedented score for that early day. There was an enormous amount of gambling on that game, for the Mutuals had a formidable club. A crowd of fully ten thousand persons filled the Union Grounds at Brooklyn, and hundreds of others looked on from housetops overlooking the field. By this time the Reds had won seventeen games without defeat, and it seemed that all New York wanted to see the streak broken. Meanwhile, in Cincinnati, a crowd of two thousand milled around the Gibson House awaiting the telegraphed score. When the news of the victory finally came through, red flares were set, salutes fired, and cheers echoed through the streets. A wire was dispatched to the team, as follows: Cincinnati, 0. June 15, 1869 Cincinnati Baseball Club, Earle's Hotel, New York: ON BEHALF OF THE CITIZENS OF CINCINNATI, WE SEND YOU THIS GREETING. THE STREETS ARE FULL OF PEOPLE, WHO GIVE CHEER AFTER CHEER FOR THEIR PET CLUB. GO ON WITH THE NOBLE WORK. OUR EXPECTATIONS HAVE BEEN MET. ALL THE CITIZENS OF CINCINNATI, PER S.S DAVIS The noble work did continue. The Red Stockings won three games in Philadelphia, one at Baltimore, two at Washington, and one at Wheeling before returning home. In July more victories were earned in Washington, Rockford, Illinois, St. Louis, 197 Baseball's Immortal Red Stockings and Milwaukee. By this time the entire nation was watching to see who would be the first to send Cincinnati to defeat. The closest call came in late August in Troy, New York. There the Reds met a team known as the Haymakers, owned by a remarkably unique character named John Morrissey, who was, among other things, a pugilist, gambler, and Congressman. Morrissey placed a large bet on the Haymakers that day, some saying the amount wagered was $60,000, a figure that may be apocryphal. But whatever the truth of the matter, Morrissey never had to pay off. With the score tied, 17 to 17, in the sixth inning, Morrissey instructed his players to get into an argument with the umpire and use this as a pretext to stop play. This was done, and the game was ruled a tie. Under present rules the victory would be awarded the Red Stockings by forfeit. The Haymakers later offered a written apology for the incident, but in the records the game remained a tie. In September the team visited California, winning five games in San Francisco from teams known as the Eagles and Pacifies. The boys returned home in October, after stops in Nebraska, Illinois, and Indiana, and brought the season to a close on November 5, defeating the Mutuals again, 17 to 8. It was at a banquet following the season that Aaron B. Champion rose to his feet and said, "Someone asked me today whom I would rather be, President Ulysses S. Grant or President Cham- — From In Memoriam — Aaron B. Champion AARON B. CHAMPION 198 The Bulletin pion of the Cincinnati Baseball Club. I immediately answered him that I would by far rather be the president of the baseball club." Who were these men who called themselves Red Stockings, and how did they fare in later life? It has been possible to trace all of them except Richard Hurley, the substitute, who went to live in Washington and disappeared in the stream of that city's life. But here is what is known to have happened to the others: Earry Wright - The manager of the Red Stockings, a kindly, gentle man became famous as a field leader in the major leagues. Patriarch of the professional game, he wore a beard and commanded the respect of his players in about the same way that Connie Mack later did. Wright managed in Boston, Providence, and Philadelphia from 1871 to 1893, then became the National League's supervisor of umpires. He died of pneumonia at the age of sixty at Atlantic City on October 3, 1895, and is buried at West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia. George Wright - Harry's young brother was the best shortstop in baseball in the 1870's. He retired as a player following the season of 1882 and founded the sporting goods house, Wright & Ditson, in Boston. That business prospered to such an extent that he became a millionaire. He died on August 21, 1937, at Boston at the age of ninety of heart trouble, and is buried in Holyhood Cemetery, Brookline, Massachusetts. Asa Brainard - The pitcher retired as an active player in 1874. He deserted his wife and little son, Truman Brainard, in Cumminsville; when the boy died in January 1879, aged seven, the mother entered the Widows' Home. In August 1882 Asa was reported running an archery club at Port Richmond, Staten Island. After being badly hurt in the back of the hand by an arrow, he drifted to Denver, Colorado, where he operated a poolroom. He became the first of the Red Stockings to die, breathing his last at Denver on December 10, 1888. Charles H. Gould - The only Cincinnatian on the team, he managed the Red Stockings in the National League in 1876, the first season that the circuit operated. He then became, successively, a clerk in the Cincinnati Police Department, a conductor on Car 612 of the Fairmount Electric Street Car Line, and a pullman conductor on the run to New Orleans. He eventually died at the home of a son, Charles Fisk Gould, at Flushing, Long Island, April 10,1917. He was buried at Spring Grove. When Warren G. Giles, Baseball s Immortal Red Stockings 199 then president of the Reds and now president of the National League, learned in 1951 that Gould lay in an unmarked lot, he had a suitable shaft of granite erected to his memory in a ceremony witnessed by the entire Cincinnati team. Doug Allison - Brainard's catcher remained in baseball through 1883, then became a federal employee in Washington, serving as a post office clerk, and guard at the National Museum. He was a talented crayon artist, and remained a lifelong baseball fan. Letters that he wrote to August (Garry) Herrmann, president of the Reds from 1902 to 1927, are now preserved at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum at Cooperstown, New York. He died of heart disease in Washington on December 19, 1916. Charles J. Sweasy - For years the fate of this player represented a peculiar puzzle because two obituaries exist. One relates that he died at Newark, New Jersey, on March 30, 1908; the second has Fort Worth, Texas, on March 24, 1939. Internal evidence would indicate that the Newark death is correct and that the Fort Worth man was an impostor. It is known that after Sweasy retired as a player in 1878 he went to Newark and became a street vendor, peddling oysters. The Texas "Sweasy" was a pioneer brewer in that state, founder of a liquor house, a Presbyterian, and an Elk. He was survived by one sister, three nieces, and two nephews — all of whom refused to answer questions by mail concerning the identity of their deceased relative. Andrew J. Leonard - Aside from the Wright brothers, Leonard was perhaps the most accomplished player on the team. Born in Ireland but a lifelong Bostonian, he played until 1882 and died at the Eoston suburb of Roxbury, August 22, 1903. Calvin A. McVey - This player, like Gould, became a manager of the Reds in the National League, piloting the team during the the season of 1879. He then moved to California, engaged in business in San Francisco, and was wiped out by the fire that followed the esrthquake in 1906. The National League granted him a small pension, and he died in the poorhouse at San Francisco, August 20, 1926. Fred A. Waterman - Although Gould was the only native Cincinnatian on the Red Stockings, Waterman became a resident of the city after concluding his baseball career in 1875. He joined the Cincinnati police force in 1880, after which he became a private watchman at the old Fifth Street Garden in 1884. 200 The Bulletin His subsequent decline, as traced through city directories, reads like the progressive degeneration of Hurstwood in Theodore Dreiser's "Sister Carrie." Waterman was at various times a clerk, bartender, bricklayer, plasterer, and day laborer. A lifelong bachelor who lived at 535 West Fourth Street, he died of tuberculosis at Cincinnati Hospital, December 16, 1899. Newspapers recalled that he had been a member of the Red Stockings, and a popular subscription of funds resulted in his being spared the ignominy of a burial in the potter's field. His remains were placed in Wesleyan Cemetery. The Red Stockings took the field again in 1870, with all the regular players returning, and started the year in the same spectacular fashion, continuing the string of victories. Early in the year they visited the South, winning games by such one-sided margins as 79 to 6, 94 to 7, and 100 to 2. But defeat came eventually, and under heartbreaking circumstances. Cn the afternoon of June 14, 1870, before a crowd of nine thousand at the Capitoline Grounds at Brooklyn, the Red Stockings were defeated by the Atlantics, 8 to 7, in eleven innings. The setback ended a string of triumphs that had reached 130 starting in 1868. After nine innings, the game between the Red Stockings and Atlantics was tied, 5 to 5. The Atlantics wanted to call the game a draw, but Harry Wright's boys insisted on playing extra innings. When the Reds scored twice in the eleventh, it appeared that victory would be theirs. But the Atlantics rallied for three runs and the game. A key play occurred when an exuberant Brooklyn spectator jumped on the back of Cal McVey as he was in the act of fielding a fairly hit ball, thereby permitting a run to score. President Champion announced the sad news in a telegram to Cincinnati: NEW YORK, JUNE 14, 1870 - ATLANTICS 8; CINCINNATI 7. THE FINEST GAME EVER PLAYED. OUR BOYS DID NOBLY, BUT FORTUNE WAS AGAINST THEM. ELEVEN INNINGS PLAYED. THOUGH BEATEN, NOT DISGRACED. AARON B. CHAMPION, CINCINNATI BASEBALL CLUB WONDER TEAM IN ACTION AGAINST ATLANTICS — From Harper's Weekly, July 2, 1870 Baseball's Immortal Red Stockings 201 202 The Bulletin Baseball fans are notoriously fickle, and their lack of support of the team following that first defeat provided an early example of the fact. Attendance at the games declined, the players became restless, and five other defeats followed before the season was over. Other teams were springing up now, and many of them made generous financial offers to the Cincinnati players. That the great team would break up was becoming apparent, a feeling confirmed by a circular sent out by the new president, A.P. Bonte, on November 21, 1870, and which read as follows: Dear Sir: According to the custom, the Executive Board reports to the members of the CINCINNATI BASEBALL CLUB its determination in reference to the baseball season of 1871. We have had communication with many of the leading baseball players throughout the country, as well as with the various members of our former nine. Upon the information thus obtained, we have arrived at the conclusion that to employ a nine for the coming season, at the enormous salaries now demanded by the professional players, would plunge our club deeply into debt at the end of the year. The experience of the past two years has taught us that a nine whose aggregate salaries exceed six or eight thousand dollars can not, even with the strictest economy, be selfsustaining. If we should employ a nine at the high salaries now asked, the maximum sum above stated would be nearly doubled. The large liabilities thus incurred would result in bankruptcy or compel a heavy levy upon our members to make up a deficiency. We are also satisfied that payment of large salaries causes jealousy, and leads to extravagance and dissipation on the part of the players, which is injurious to them, and is also destructive of that subordination and good feeling necessary to the success of a nine. Our members have year after year contributed liberally for the liquidation of the expenses incurred in the employment of players. We do not feel that we would be justified in calling upon them again; and, therefore, for the reasons herein stated, have resolved to hire no players for the coming season. We believe that there will be a development of the amateur talent of our club, such as has not been displayed since we employed professionals, and that we will still enjoy the pleasure of witnessing many exciting contests on our grounds. We take this opportunity of stating that our club and grounds are Baseball's Immortal Red Stockings 203 entirely free of debt; and, deeming it our first duty to see that they remain so, we pursue the course indicated in this circular. For the executive board, A.P. Bonte, President So died the Red Stockings, but their legend was already secure. Their feat of playing an entire season without defeat was unparalleled. More important, their action in bringing publicity to the city and the game led to the formation of teams that made possible a professional league of players. All nine of the Red Stockings joined that league, the National Association of Professional Baseball Players, in 1871. Two of the team, George and Harry Wright, are now members of the Hall of Fame at Cooperstown, a select gallery that includes only eighty-six of the ten thousand men who have played in the major leagues. The last chapter of the story of the Red Stockings took place at Cincinnati on October 25, 1916, when the tokens and relics of the historic team were sold at public auction. Included were a group picture of the team, a faded uniform, three of the original baseballs used in 1869, the cap of Asa Brainard, and a rubber mouthpiece used by Allison, the catcher. At the Stacey auction rooms on Gilbert Avenue, these sentimental relics were sold by the estate of Harry Ellard, who had guarded them until his dying day. There were two principal bidders: Garry Herrmann, who wanted the mementos for the office of the Reds; and William C. Kennett, Jr., son of a man who served the Reds as president in 1880. Such sentiment as Herrmann felt could not compete with the bidding of Kennett, who purchased the souvenirs. They were later destroyed in a fire at his home. But one reminder of the glorious story escaped. The old clock that ticked away the hours in the office of the club is now measuring time at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. It was kept by the family of Aaron B. Champion and donated to the Hall of Fame in 1960 by Robert Champion Rowe. In a letter to the author of this article, Aaron Burt Champion Rowe, a descendant of the president of the Red Stockings, recently wrote: In October of 1919 as my grandmother (Mrs. A. B. Champion) lay dying, she in some of her lucid moments hoped to 204 The Bulletin hear of the Cincinnati Reds winning a World's Series. She died just before the final game and she never knew of the scandal that followed. But downstairs in the kitchen of that house the old clock was ticking out those fateful moments. When we moved in 1924, the clock was taken down. I am reminded of some lines in Longfellow's poem - "The Old Clock on the Stairs." '0 precious hours! 0 golden prime, And affluence of love and time!' " HOW A REPORTER ADJOURNED THE CITY COUNCIL — 1861 The City Council met as usual last evening, and was called to order after the members present had got through with their wonted preliminary confabulation. Several papers of no value to any but the owner were offered, and passed by the unanimous vote of the respective individuals offering them. The representative of a timehonored constituency introduced a bill to paint a lamp-post in the Eighteenth Ward, which caused the lightning bolts of eloquence and the thunder gusts of oratory to electrify the hall in a manner undreamed of by Demosthenes and never attempted by Cicero. Probably the twilight of this glorious anniversary would have shed a dim luster over one of the City Fathers, as in Websterian attitude he demonstrated the impracticability of the project spoken of, while his brethren in authority paid the silent homage of attention to his words of wisdom, but for the announcement, privately circulated by an ingenious local, that a dispatch had been received at the newspaper offices, containing the sad news of the defeat of the Federal troops at Alexandria, and the contemplated march of Beauregard into Washington immediately. The sympathetic nerves of the City Fathers were stirred, and with unutterable anguish portrayed in each countenance, a motion to adjourn was passed instanter. The official dignitaries, after a vigorous feat of pedestrianism, reached the newspaper offices only to learn that they had been the subject of a mercantile transaction, commonly called a "sell." Cincinnati Daily Gazette, July 4, 1861.

© Copyright 2026