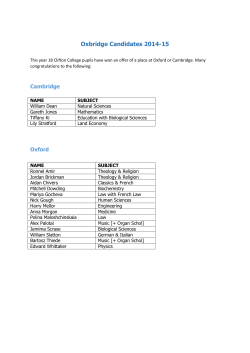

Religion and Philosophy