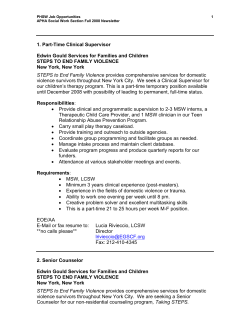

Delegate Reference Materials - American Pharmacists Association