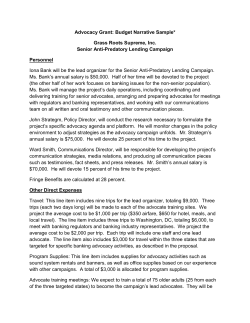

Building Blocks for Change: A Primer on Local Advocacy for