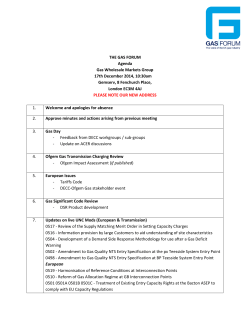

Suppliers-Governance-Demand