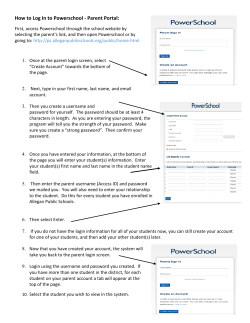

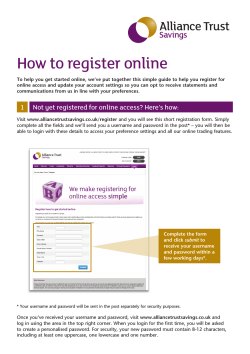

How-to Booklet