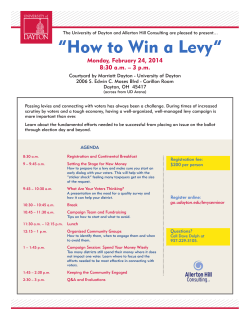

Document 249875