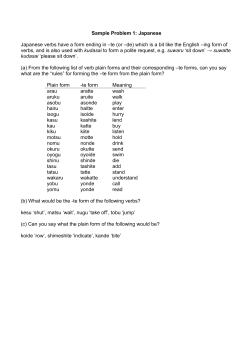

Current Print Edition* April 2015 PD