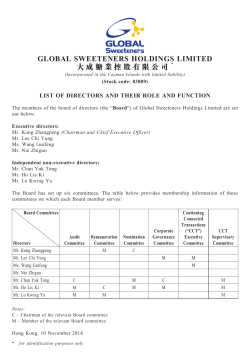

Optimal board independence with non