How to Measure Sales Against Market Potential in Construction

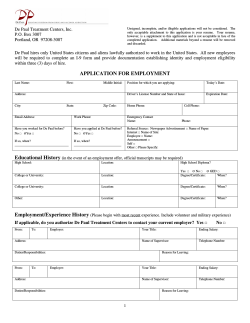

How to Measure Sales Against Market Potential in the Construction Industry KENNETH R. TELFER Sales managers of building products selling +o new construction often ask: • How can sales be related to market potential? • How can market penetration be determined? • How can more realistic sales goals be established? Here is a simplified statistical answer to these questions, based on constructioncontracts activity. for those with sales and research responsiF ORTUNATELY bilities in the field of new construction, the problem of relating sales to market potential can be tackled more readily and probably more accurately in the dynamic construction industry than in many other industries struggling with the same problem. The explanation lies in the reliability of the economic indicator with which sales or shipments can be correlated—construction contracts. Construction contracts are commitments for future construction. Many a contemplated job never gets beyond the planning stage. But once a contract is awarded, a commitment has been made: the job will go ahead. Buying action begins because this commitment establishes needs; and only when needs exist can sales be made. A vast series of purchases of products and services to supply those needs takes place as the j'ob progresses from plans to completion. Thus, detailed construction contracts as they are accumulated from month to month for any given area summarize the total construction activity in any given project type for the particular area and month in question. In short, these data, expressed in numbers of projects, square feet of new floor space, or dollar valuation, reliably represent the entire potential market in new construction to which a manufacturer, distributor, sales agent, or dealer can sell his products. Individual firms selling building products, materials, and equipment compete for this known potential. It is logical to assume that there is a direct relationship between product sales or shipments; and the amount of building that takes place of the type that represents a market for that product. Depending on whether the product goes into a new project quite early, somewhat in the middle, or during the later stages of construction, there will be a corresponding time lag between the construction contract and the point when shipment is made to the market. Inventory buildup or depletion sometimes has a bearing on this time factor. Usually an average time lag can be determined. When it is found that shipments correlate with the appropriate construction contracts, and a consistent time lag exists between contracts and shipments, a firm can measure current sales performance against market potential for individual sales territories, or in aggregate, and also engage in more accurate quota setting and forecasting. 35 Journal of Marketin}^, January, 1962 MeaHuring Current Sales Performance Correlation analysis LS simply a method of measuring the relationship between two sets of factors. To measure sales performance against market potential, it is first necessary to discover a relationship between the fluctuations in a company's sales or shipments and the appropriate construction coniracts; next to determine the dependability of the relationship; Mnd then to obsei-ve the number of months by which sales, or shipments lag behind construction contracts.. This much established, there remains merely the process of dividing construction contracts into the sales or shipment figures, appropriately lagged, to obtain the dollars of "take" from the market. These are the payoff ratio figures. Expressed as dollars of product sold per thousand dollars of new construction of the kind to which the company sells, these sales ratios are completely valid for comparing territories one with another or with the over-all company ratio of market penetration. The month-to-month trend of this latter ratio dearly indi.cates the progress the company makes in keeping pace with market potential. Those sales territories showing the lowest dollar of "take" from the market are disclosed as areas of weak pcn-formance where management will want to take remedial action. Procedure Three preliminary considerations regarding construction contracts require attention before taking the few simple steps incident to relating the two series of data: 1. Careful .selection of the project types representing the market for the product. 2. Determination of the unit of measurementnumbers or projects, square feet of floor area, or dollar valuation. •i. Establishment of the geographic area or areas to hi, studied, This may be a single county, grraips of counties, a state, groups of states, or all states. Example to Illustrate Procedure The A.R.C. Company, with headquarters in Newark, sell, s.nd, gravel, cement, concrete, and cinder block throughout northern New Jersey. It maintains a branch office in Jamaica, with salesmen selling over most of Long Tsland; and another branch in Philadelphia, with salesmen covering all the metropolitan area counties. !t keeps its records by shipment;-:. A.ii.C. attempts to sell its materials to all nonresidential and residential projects. These provide or underlie construction contracts for the classification known as Total Building, and are broken out mto Total Nonresidential and Total Residential Building-. As to the significant unit of measurement: A.B.C. relates its materials shipments to the number of square feet of Total Building in each of the three areas to be studied, since the floor area of most buildings has a direct bearing on the quantities of the company's materials that are needed. To use dollar volume of construction contracts as the statistical unit of measurement in this instance could be somewhat misleading, since high-cost buildings would not necessarily require more building materials of the kind sold by A.B.C, than low-cost structures. Having selected Total Building, with breakouts for Total Nonresidential and Total Residential as the proper project classification to represent the total potential market; square feet of floor area as the best unit of measurement; and northern New Jersey, Long Island, and Philadelphia and vicinity as the three areas to be studied, the setting: up of a continuing procedure now involves five basic steps. These steps are fundamental to all correlation studies. It is not unusual to employ similar steps in relating two series of data. But to many in the management of iarge and small businesses serving new construction, the concept of applying this method to construction contracts as representative of market potential is unique. Its reliability is authenticated by the accuracy of construction eontract data m reflecting the total market of available business. First, it is necessary to combine all throe branch areas, and relate total shipments to Total Buildmg. The same procedure is repeated with respe^H to detailed studies of each branch: first, for branch .shipments to Total Building in the branch area next for branch .shipments to the Nonresidential market, and again to the Residential market in the branch area. Detailed to this extent, weak and strong area, of .selling become readily ;,pparent. Step 1 Post monthly figures in thousands of square feet of Total EuiJdin,^ for a period of four to five years (Table 1). This represents an adequate period over which to determine correlation, and observe the lajr time between shipments and construction contracts' • ABOUT THE AUTH"O"R7 "K7ni^;fhX Telfer has been a Marketing Con-.ul+ani in New York for the last ten years with the F. W . Dodge Corporation. His previous experience was as an Assistant to the President of the Crowell-Co)l;er Publishing Company; and subsequently, as owner and publisher of the East Hartford Gazette, New England's oldest, continuously published, weekly newspaper. . . " ^ " / ' I l ' / T r ^ , ^'' ^•^•^- '" f^^^t-f'"g from the HarAB d t i 1 ^"''"''^ A d - ' " ' ^ ' - ^ - . . following an A.B. degree cum laude from Oberlin College. 37 How to Measure Sales Against Market Potential in the Construction Industry TABLE 1 A . B . C . COMPANY PRODUCT (UHIT Yr.- Honth January f«bru«ry Harch Atrl) Hay Juna July 5«pt«al>ar Octobar Novainbar Dmevtbtr YEAR Ho. April Mar July »UOU.^t Saptembgr Octobtr Noveirbar Deombcr YEAR $ ): Yr.M.T. 447 754 827 776 874 895 868 875 880 757 629 8995 16495 15939 22902 22051 22616 16360 22797 15310 17696 21253 1599! 23248 ^32658 Yr.. 1955 H.T. Ha. 487 687 739 715 822 767 809 849 779 760 480 502 739 785 952 1082 910 917 940 870 878 7(0 9795 Mo. 18870 18332 24899 24991 32662 26249 22908 16869 21553 24208 24208 25380 281129 Yr.- I Northern New Jersey Area8:\ Long Island ^^Philadelphia and Vicinity Yr.M.T, 235033 237426 239423 242363 252409 262298 262409 263968 267828 270780 ^278997 281129 Ho. Yr.- 1957 Yr.M.T. M.T. 1958 Yr.M.T. Ho. Ho. M.T. 497 9111 497 9499 559 9874 341 519 9453 8933 9937 565 656 9854 662 9459 529 8800 820 9495 786 8766 784 9853 1001 9902 961 9455 898 8703 1042 9862 804 9217 969 8868 877 9829 921 9261 885 8832 94f 9823 852 9J72 869 8849 767 9650 870 9275 877 8856 962 9742 963 9276 820 8713 864 9728 722 9134 680 8671 543 9563 520 91)3 9561 9111 Northern K. J. and Long Island, N. Y. countiea; Philadelphia vicinity counties of BerkSj Bucks, Chester, Dauphin, Delaware, Lancaster, Lehigh, Montgomery, Northampton, Philadelphia, and York. 9062 9117 9102 9060 9236 9444 9459 9538 9603 9593 9714 9795 Yr.- 1955 1956 Ho. TOTAL BU;LlflHfi tr.- 1954 M.T., SHEET t1.T. Ho. 843! 8391 8458 8546 8607 8659 8787 8846 8872 8973 8970 8995 M-SQ.FJ.) Ind: Tr.- 1953 TOTAL WORK BUILDING MATERIALS - SHIPMEHTS 1(13 eoij 8452 MOVING 1954 4311- Mo. Januarj' Fobrusry March M- 1953 CONTRACTS (UHlT Honth 12-MOUTH M.T. 1956 Mo. 22097 284356 23948 21467 287491 25209 32086 294678 32182 29192 298879 34567 23963 290!80 30972 26320 290251 24! 82 34537 301880 258! 4 24488 ^ 0 9 4 9 9 24867 21825 30977! 20085 25833 311396 21440 24018 311206 20151 30243 316069 18344 316069 J0I76I Step 2 Post monthly dollar shipment figures, in thousands, for the ^ame period of time. See upper half of Table 1, The two series of data are thus contained on a single sheet; and as figures for future months become available, they may be posted to the same sheet. Step 3 Convert these figures for both sets of data into 12-monlh.s moving- totals or 12-months ending- figures, as they are more properly called. This eliminates the se;isonal element which exists in all new construclhm. ennhllng the true trend to hecome diseernible. Table 1 shows the process whcroby 12-months ending figures are obtained by adding the new month to the total ^or the preceding- twelve, and subtracting- the same month a year ago, Step 4 Plot the two series of 12-moriths ending figures on separate sheets of semi-logarithmic tracing paper. Semi-log paper makes it possible to match the rate of change, up or down, of the two completely different series of data, regardless of their Yr.- 1957 M.T. Mo, 317920 321662 321758 327133 334142 332004 323281 323660 321920 317527 313660 301761 !6489 14340 25664 20856 24582 24351 22638 23125 20036 21690 21769 13776 249316 M.T. 294302 283433 276915 263204 256814 256983 253807 252065 252016 252266 253884 249316 Yr,- 1958 Mo, 14098 14034 18409 19509 24423 20628 24770 27261 27238 27459 22678 Yr.M.T, »o. H.T. 246925 246619 239364 238017 237858 234135 236267 240403 247605 253374 254283 magnitudes, on an exactly comparable basis. When the construction contract sheet is superimposed over the shipments sheet, and the two tracings compared, the construction-contracts sheet may be moved to the right until the curves of both series most closely coincide. It only remains to i)bperve the numbiar of months by which the shipments curve lags behind the construction contracts curveFi'jure I shows the two series on a consolidated graph, with construction contracts foreshadowing a market for A,E.G. Company materials three months in advance of shipments. When construction contracts are recorded for January, for example, shipments are made to those jobs in April. That is why the first point on the chart for construction contracts is the 12-months ending figure for January, 1954; and the first point, on the same vertical line for shipments is the 12-months ending figure for April, 3954, As the 12-months ending figures are plotted for al! the months in 195'1, 1955, 1956, 1957 and 1958, this Jead-lagr relationship continues until the iast 12-months ending figure of construction contracts extends three months beyond the last 12-months ending figure for shipments. 38 Journal of Marketing, January, 1962 70J. .1 •J 1 1 1 1 1 1 — j J ]— Kewarfc and No. K.J. cojTitiBs: Phlla. anil lurraunding counties; Long Island, K. T. — Unit! 601. » IPH 50 3 - Dallirg 2 C KST il T 0 th 0 ing T t a l f ot>l It side t 40 _ al 8 1 di 9 \ enti d 1 — t 0 1 C 20,. 1 . — • , ^ • r*- ' • ,—-— ~ ———-^ .' ——^-.J - ^ - ^ • - _ ^ — 9 1 ^ —^— • ip 7 L— u-—• 1 — ._ _ • — ^ - HI —U j --, D| I ( M A » In iy A S 0 K 0| J F M A M Jn 1, As - - 0 N 0 jj s / ' / - 1 z S 0 NDJJ F M A H I o l y f l S O H C Djj F M A M J n J ^ A S O N D - I - 1 - - 1 _ - 1 - 37.32 36.88 36.07 1 j 6,671 g 8,858 .i B.832 36. 12 s 3,933 36.21 33.28 35.19 ! 9.172 9.275 9,276 9,217 9,728 30.06 i o 29.91 29.07 30.05 o 30.78 I - - - q 1 3 11 s s 1 1 1 ] k 11 11 Oct il _ - - 1 31.93 31.78 s _ — 1 9.795 9.a74 9.937 9,861 9.863 9,902 9,962 9,829 9,823 9.650 32.87 32.38 ? 9,603 9,593 1 • I _[ - - - 1 - 9.117 9. 102 9,060 9.236 9,111 33.98 33.59 B,970 33.82 36. 17 8,787 s s 966 e 8,6iT^ 8,607 ' ? ^ - '- - 1 SHIPMENTS A ; - ' •» 30 al ui M A hi Jn J - s - i; F A K In Jy A S 0 N • ^ - o T -A ae I -^ •^— f - • M B 3* K I F M O§ ^= ---^ — 8,766 8.703 '- - -[ A U In J, A S 0 N D J F H A M In J) A S o n 0 J F U A U In Jj A 3 0 N D11 F U A M In !> A s 0 N 1<<H ISiS t I'JSt i 1951 1 _ 1 _ 1 1 f M A M Jo Jl * S 0 H D^l J F H A M Jn J» A S 0 H COD riOd CO •TS M FMEITS p \ — • — • •—-s 8_ ii _—-"^ -'^^__— 1 . e j 1 I2 11 I I i 8 ss il t 283,133 1 317.627 313,660 1 323,231 323,660 c 3I6.0B9 317.920 3 21,662 321,758 327,133 ! 309,199 290,180 267,825 270,780 I s ! 262,103 236,033 CONSTRUaiON CONTRACTS - d s FIGURE U1 1= r sa o T 1 I y H ^' \ \ S 1 J; — i a s 1 1 •i 1. A.B.C. Company—shipments of buildinf? materials—selected territories vs, total building;. Step 5 The final step indicates the extent to which sales are penetrating the market. It is simply the ratio between construction contracts and shipments, obtained by dividing one into the other, lagged three months in every instance. In this way, current sales performance is measured against market potential. The ratios reflect the dollars of product sold per thousand square feet of floor area. Inspection of the three columns of figures at the bottom of the chart in Figure 1 shows the computations. The 12-months ending figure for January contracts is divided into the 12-months ending figure for April shipments, to disclose $36.36 of materials sold per thousand square feet of floor area. As these ratios are continued, and plotted on the arithmetic scale immediately above, it is evident that the company is losing ground in its shipments to the total available market. This loss of market penetration moves downward from 1954 almost uninterruptedly until the low point of $29.07 is reached in mid-'56. From here on, the company begins to acquire an in- How to Measure Sales Against Market Potential in the Construction Industry HEWARK Total Bldg. Non Res. PHlLADaPHIA Total Bldg. JAMAICA Total Bldg. Non Res. Res. Hon Res. Res. t: :!. Newark. Philadelphiji iin<i Jjimaica bianehes. t-reasing share o±' the available business. A new hig-h of $37.82 in market penetration is achieved in August of 1958. The subsequent falloff during the next two months may only be temporary; and for good and sufficient reasons well known to management —disruption of selling actively hy vacation schedules, a strike, inclement weather and the like. Tf the eatise is unknown, however, this two moTiths' decUru: t^mivda a warning note to A.B.C.'s top management to look into all aspects of sales activity for signs of a letdown in selling efficiency, possible loss of patronage owing to late deliveries, or lower price quotations by competition. Analyses <vf individual sales territories would appear to be indicated. Sales Perforiiunicc By I crritories During- the last year covered by this study, note that tbe A.B.C. Company averaged approximately $3G.5i) of product sold per thousand square feet of flour area to Total Building. The Newark office averas^^'ed approximately SCO for the same period to Total Building. This outstanding performance record may be explained in part ;)t least by what is known ;is S.P.F- (Sales Propinquity F a d o r i . K.P.F. Ls presumed to enable a home ofiice location to sell proportionately greater volume \o its local area than branch office areas. Advances are i'e;jris t ered for all Newark ratio curves: shipments vs. Total Biiiiding, Nonrc'sidcntial. and Residential 'Figure 2 ' . Res. Penetration ratio While not nearly a.s high as Newark, Philadelphia nevertheless shows an average of $34 in shipments vs. Total Building, about equal to the company's 5-year average, and reflects a good selling job of holding position even to the point of improving it, in the face of a declining construction market. Figure 2 reveals that if any additional effort were deemed necessary to boost sales in this branch, it would take the direction of inquiry into sales to the Nonresidential Market. Jamaica turns out to be the only branch with a poor showing. During the most recent three months, two things happened: The 12-months ending construction contracts definitely moved upward, while 12-months shipments declined. The result, of course, is a sharp drop in the penetration ratio curve of shipments vs. Total Building (Figure 2). Undoubtedly this is responsible for the faUoif in tde over-all company operation (Juring the latest month or two. Further insight into this loss of market penetration is gained from the fact that while the penetration ratio curves in both Nonresidential and Residential have slipped recently, the decline is more pronounced and of longer (iuration in trouble spot that management should first take the Residential segment. It is, therefore, in this action. Many factors could account for this slippage, including the noed £m- adding more manpower or even the transfer or replacement of salesmen :n this hi]?hiy competitive Long Island mai'ket. 40 Journal of Marketing, January, 1962 Setting Sales Quotas and Estimating Future Business Quota setting is a function of forecasting. Quotas are baaed on the volume of business estimated for future months. It has been seen that construction contracts led the A.B.C. Company's shipments by three months. In itself this is a forecast—a forecast which, in effect, has already been made. A glance at the company's chart, Figure 1, gives a rough preview of what may happen to shipments some three months hence if they follow the course pursued by construction contracts. To obtain a more specific and accurate forecast in terms of estimated dollars of shipments, however, the ratios are projected three months ahead on the penetration-ratio portion of the chart. Each of the three projected ratios is then multiplied by the corresponding 12-months ending figure for construction contracts. This reverses the process by which the earlier ratios were obtained. The results are the estimated dollars of shipments (in 12-months ending figures) that may be expected for each of the succeeding three months, assuming selling efBciency continues at the same rate and that competitive conditions remain about the same. In sum, a statistical approach can be helpful in the setting of sales quotas, at least for the period of months represented by the lead-lag relationship of a correlation, and for a projection beyond that point. Most companies selling to new construction place their chief reliance on field reports and personal observations weighed and adjusted, where necessary, by management judgment in the light of past sales, knowledge of industry conditions, and analyses of sales expenses to sales volume. A statistical approach, employing lead-lag correlation of two key series of data dealing directly with performance and market potential, can assist in preparing more realistic quotas. Applications of Method Faced with rising competitive pressures and mounting costs, most firms today recognize the need for improved sales controls. They are looking for new ways to measure sales performance, and new means to make more accurate sales predictions. In a market as large and complex as the giant construction industry, relatively few are interested in the total market. Most companies selling within the new construction market become specialized with respect to size, product mix, areas of operation, and type of business; and hence their needs for market information are correspondingly specialized. To determine their market potential, they need only those project types in construction contracts that represent the market to which they sell. In measuring sales performance against market potential, they need construction contracts expressed in the unit of measurement best suited to their type of business. Their sales areas may be limited to a single county or group of counties, or they may cover the nation, broken out into major sales districts—and for this they need the data that construction contracts can supply along county and state lines. The A.B.C. Company, selected to ilustrate statistical procedures for large and small firms in the method under consideration, also sei'ves id illustrate the specialized market informational needs of individual concerns. Obviously other firms would require different market data. A ceramic tile manufacturer, for examjjle. selling nationally through distributors and tile contractors, would still work with square feet as the best unit of measurement for market potential, as there is a direct relationship between sizes of various buildings and square feet of tile required. Since he sells relatively little tile to Manufacturing Buildings, however, he would exclude this large category from his project data. Construction contracts have been found to lead shipments by five months in the tile industry. A leading manufacturer of hospital operating equipment, sterilizers, and surgical supplies finds that booked orders follow square feet of hospital construction contracts very closely with a 4months lag, and that shipments move similarly with excellent correlation ten months after contracts. A steel company selling pipe and road fabric to sewage systems, roads and highways, airports and landing strips (with an average lag of about two months behind construction contracts) would express its share of this market in terms of tons of product per thousand dollars of specific engineering contracts. One- and two-family houses and apartments are an important market for a boiler or furnace manufacturer. Since he sells but one boiler or furnace to a house or apartment building, units or numbers of houses and apartment buildings are his yardstick for measurement. The same set of conditions pertain to the manufacturer of "central plant" residential air-conditioning equipment. Again, a manufacturer or large distributor of bathtubs and bathroom fixtures can work equally well with dollar figures or fioor area, since larger houses and apartments require more bathrooms. These examples typify some of the ways in How to Measure Sales Against Market Potential in the Construction whicli specialized market information can be used in a simplified statistical approach to a more systematic control over sales. Forecasting, tieasonally adjusted, can be employed by the skilled researcher to give this method added benefits. There is, however, no easy push-button method for forecasting". As a means for predicting future sales, at least to the extent of the lead-lag relationship between two series of data, this method 41 Industry serves a useful purpose in helping management to make better judgments. In all this, there is helpful guidance in measuring sales efficiency; locating weak distribution districts and controlling sales more scientifically; planning raw material stocks and finished goods inventories; allocating advertising expenditures by areas; and setting more realistic quotas and sales goals. MARKETING MEMO Capital Investment A recent study conducted by the author has revealed that a majority of the nation's largest business firms fail to employ a theoretically sound approach to the expenditure of funds for capital investment. These firms fail to recognize two basic principles which economists regard as unarguable. They are: (1) that time has economic value, (2) that the mere rapidity with which an investment is recovered is not an indication of the profitability of the investment. —Donald F. Istvan, "The Economic Evaluation of Capital Expenditures," The Journal of Bttsme.'^.s, Vol. 34 (January, 1961), p. 45. RsprintH of every article in the following prices: Single reprint Two reprints Three reprints are available (as lonci a--^ supply lasts) at $1.00 1.50 1.80 Four to 99, each First 100 Additional lOO'f .? .50 40.00 20.00 Quantity Discount Special prices for large quantities. Send your order to: AMERICAN MARKETING ASSOCIATION 27 East Monroe Street, Chicago 3, Illinois Duplication, reprinting, or republication of any portion of the JOURNAL OF MARKETING is strictly prohibited unless the written consent of the American Marketing Association is first obtained.

© Copyright 2026