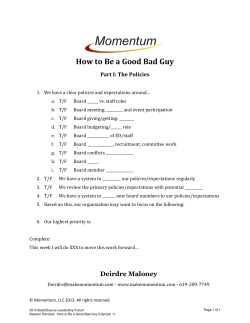

Document 211940