Te ☞ Printing arts

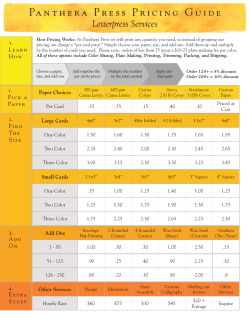

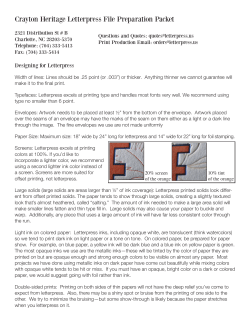

☞ Te Printing arts n By S o nja H a k a l a Photography by J o n G i l ber t F o x T he windows of Bob Metzler’s basement studio in North Thetford, Vt., give viewers an eye-level perspective across an expanse of frozen grass to the Connecticut River, almost lake wide at this point in its journey from north to south. The natural light that streams into the large space, even on a frosty morning in midwinter, illuminates a scene that makes visitors feel as though they’ve stepped back into the 18th century. Metzler is a devotee of letterpress printing, what some enthusiasts call “the black art.” This is the print technology that ruled the world from the time of Johannes Gutenberg’s inventions in the 15th century until it was superseded by more mechanized methods in the early 1900s. It was once the norm for putting every sort of document — from magazines to books, broadsides, pamphlets, calling cards and stationary — on paper. While Metzler’s fascination with this method of printing is not genetic, it’s close. “My mother bought me a toy printing press when I was 10,” he explains. “I still have it in a case in my shop.” continued on PAGE 28 26 Upper Valley Life Bob Metzler in his North Thetford, Vt. letterpress studio. He is holding a composing stick with the 19th century DeVinne wood type. 27 The Printing Arts continued from PAGE 26 When Metzler was in eighth grade, his parents upped the ante by giving him a tabletop version of a hand platen press accompanied by drawers full of metal type. A platen is the plate part of a press where paper is held while it is kissed by inky letters that make an impression that we can read. There is an equivalent in typewriters in the rubber-coated cylinder that holds paper in place while an operator strikes the keys. “This was a common gift given to boys throughout the 1800s,” Metzler says. “There was a company in Meriden, Conn. — the Kelsey Company — that sold kits with presses, type and the other tools you need to print by hand.” By the time he entered college to major in print management, Met(Above) Composing metal zler had his own letterpress shop in type and (right) the printed his family’s garage where he earned sample with a photo extra cash by doing commercial engraving. The blue ink used work. Though interrupted from was a special formula made time to time, Metzler’s devotion of three different inks. to letterpress and setting type by equipment availhand has remained constant in his life. able for those who He’s been seriously collecting equipment, want to produce tools and cases full of metal and wooden beautifully printtype since 1957. He once ran a weekly ed books, posters, newspaper in Windsor, Vt. (the Windsor invitations and Chronicle), which had a letterpress shop, brochures by and now teaches the book arts workshop hand. Mechaniat Dartmouth College as well as giving cal presses, such classes in his own shop. Printing by Hand as the eight in Metzler’s basement shop, Even though no one manufactures were built to last. “As long as you oil the machinery you need for letterpress them, a hand-operated press just goes on printing any longer, there is still plenty on and on,” Metzler says. Unlike other types of printing, such as digital or offset, letterpress is a handson art, craft and skill. Every element that You know the “Wanted” posters in goes into the application of ink to paper old cowboy movies? Well, the original in letterpress involves touch. “Wanted” posters were probably As any practitioner of handcrafts printed using wood type. Fonts will attest, the act of personal creation in larger sizes are made of wood gives one a new appreciation for many because they are lighter and easier to of the articles we live with every day. use. Since there’s not a huge call for Anyone who’s ever knitted readily underbillboard-sized lettering, the wood stands the effort behind a sweater or a actually lasts quite a while. well-made pair of socks. With the touch of a finger, a woodworker perceives the Wood vs. Metal Type 28 skill and time that goes into a bit of well-done joinery. And when someone such as Metzler gazes at a well-designed book, he is aware of the impact that the combination of font, spacing and placement have on a reader’s pleasure. In other words, if you’ve ever spent time setting a few lines of type by hand, you will be forever awed by the existence of books. As with other handcrafts, it’s important to decide where you want to go before you begin. That’s why Metzler starts every class in his well-organized basement with the same question — what do you want to print? A coupon book for Christmas giving? Tickets for a community theater performance? Business cards? A poster? That question is followed by others such as: What sort of paper do you wish to use — something smooth and white like an index card or perhaps a cream-colored page that feels slightly rough to the touch? When all is said and done, how big will your final project be? Like many devotees, Metzler is a historian about the object of his passion. He can tell you where many of the presses that he owns were once housed, and lovingly describes how he rescued some of the wooden cases where his collection of fonts are kept. He relates how 19th century typesetters held contests for public entertainment to see who could put a page of type together in the fastest time. One famous typesetter could correctly pull the letters, spaces, numerals and punctuation together for a page while blindfolded. If you turned the drawer holding the letters upside down, he could still set type accurately. Where to Start Metzler explains that typography begins with a student’s selection of a font. A font is the term used to designate all of the letters, numerals and punctuation marks made in a certain style and meant to be used as a group. There are Upper Valley Life more than 1,000 fonts — in both metal and wood — in Metzler’s collection. (See sidebar) When you set type by hand, all of the letters, spacers, numerals and punctuation you need of your chosen font in your chosen size are contained in partitioned wooden drawers. The drawers and the cases that hold them are beautifully made with rugged joinery that catches the eye. The letters in each drawer are arranged according their frequency of use. This is the same reasoning that explains why the top line of letters on a keyboard are Q-W-E-R-T-Y and not A-B-CD-E-F-G. Since it can be difficult to determine which letter you’re holding — the metal has been well inked over the years — Metzler supplies a diagram marking the location of the small letter e, the capital letter M or the en spacers you place between words. As they are selected, each letter is placed in a hand-held composing stick, face up but backwards so that when they’re inked and pressed to paper, the letters appear in their readable form. When the composing stick is full and all of the lettering is spaced correctly, the student steps up to a proofing press where the acid test will be administered. Are all of the words spelled correctly? Are all the letters turned in the right direction? Are the spaces between words, sentences and paragraphs correct? Suddenly, the student becomes aware of the delicacy of type, the care needed to produce an eye-pleasing bit of text. How much ink is enough? How much difference does the choice of paper make? And what’s involved if you want to print something in more than just one color? Jane Applegate from Sharon, Vt., takes a letterpress class. She inks up the plate (above) and pulls the lever (below) of the tabletop platen press to make an impression. Guardian of the Art As other forms of printing — offset and then digital — became the norm in the 20th century, the letterpress print industry imploded. Owners literally threw away their hand-operated presses and cases of type as interest in letterpress printing faded. But like so much else in our society, letterpress never died continued on PAGE 31 November 2010/February 2011 29 The Printing Arts continued from PAGE 29 completely. In fact, it’s now enjoying a noticeable resurgence all over the United States and Europe as enthusiasts gravitate toward the quality of this hands-on craft, and enthusiasts such as Metzler are considered the guardians of the art of printing. Metzler notes that unlike the letterpress practitioners of previous centuries, most of the contemporary enthusiasts are women. In fact, most of the students at his workshops at Dartmouth and the classes he teaches in his North Thetford home are female. There are now letterpress societies, museums dedicated to printing, people carving molds for new fonts to be used on hand platen presses, and a lively online trade in printing tools. Rare book enthusiasts pay large sums for books printed with letterpress technology. Martha Stewart sparked a national lust for wedding invitations printed in this fashion with a spread in one of her magazines, and Metzler receives a weekly newspaper from Colorado that’s typeset and printed by hand. “He won’t let me pay for it,” Metzler says of the publisher. “I keep sending him money but he keeps sending it back.” When asked why so many people are drawn to letterpress printing, Metzler points out that the handcrafted quality of this art is easily seen. “It’s not perfect because every decision and every move made by the printer is reflected in what you see on the paper,” he says. In a world where the push is toward sameness, that quality makes all the difference. Learn More Bob Metzler teaches letterpress printing and typesetting in his home studio in North Thetford in day-long workshops on the first Saturday of each month from November through April. You’ll find his phone number in the book, as Metzler says, or you can reach him at his home address: PO Box 85, North Thetford, VT 05054. November 2010/February 2011 31

© Copyright 2026