Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in

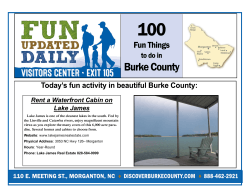

Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Jan Åberg Department of ecology and environmental science SE-901 87 Umeå Umeå 2009 Copyright © Jan Åberg. All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-91-7264-878-4 Cover photos by Jan Åberg. Printed by: VMC-KBC, Umeå, Sweden, 2009. Till Susanne, Noomi och Miriam Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..................................................................1 The global carbon cycle ...............................................1 The role of lakes...........................................................2 Production of CO2 in lakes...........................................3 Emission of CO2 from lakes.........................................4 Aims and outline of the thesis.....................................5 METHODS............................................................................7 Hydrology, meteorology and water chemistry............7 Carbon measurements................................................8 Net CO2 production.....................................................8 Emission of CO2.........................................................10 Statistics (selected approaches)................................10 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION............................................13 Causes of CO2 variation in the surface water............13 Internal CO2 production............................................14 Fluxes of CO2 to the air..............................................15 Concluding remarks...................................................16 SVENSK SAMMANFATTNING ........................................19 Artikel I......................................................................20 Artikel II.....................................................................20 Artikel III....................................................................21 Artikel IV....................................................................22 Avslutningsvis............................................................22 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................23 REFERENCES....................................................................25 + Four research papers, listed on the next page List of Papers PAPER I: Anders Jonsson, Jan Åberg and Mats Jansson (2007): Variations in pCO2 during summer in the surface water of an unproductive lake in northern Sweden Tellus Series B-Chemical and Physical Meteorology, 59(5), 797-803, doi:10.1111/j.16000889.2007.00307.x. PAPER II: Jan Åberg, Mats Jansson, Jan Karlsson, Klockar-Jenny Nääs and Anders Jonsson (2007): Pelagic and benthic net production of dissolved inorganic carbon in an unproductive subarctic lake Freshwater Biology, 52(3), 549-560, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.2007.01725.x. PAPER III: Anders Jonsson, Jan Åberg, Anders Lindroth and Mats Jansson (2008): Gas transfer rate and CO2 flux between an unproductive lake and the atmosphere in northern Sweden Journal of Geophysical Research-Biogeosciences, 113(G4), doi:10.1029/2008JG000688. PAPER IV: Jan Åberg, Mats Jansson and Anders Jonsson: The importance of water temperature and thermal stratification dynamics for temporal variation of surface water CO2 in a boreal lake Manuscript submitted to the Journal of Geophysical Research – Biogeosciences Paper I and II is reprinted with permission from Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Paper III is reprinted with permission from the American Geophysical Union. J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Introduction Introduction This doctoral thesis aims to bring further knowledge about production and emission of carbon dioxide (CO2) in lakes. This first chapter begins by introducing the global carbon cycle and its importance for the atmospheric CO2 concentration. Then, the role of lakes as CO2 sources, and the processes of in-lake CO2 production and emission, are briefly reviewed. The last part of the introduction gives the specific research aims of the thesis. In the chapters following, the research methods and results are summarized and discussed, with references to the four included research papers. The global carbon cycle The greenhouse effect caused by heat absorption in the atmosphere, has regulated the climate on Earth for billions of years. Water vapor (H2O) is the most important greenhouse gas, followed by carbon dioxide (CO2), which has contributed to climate regulation during most of the time of abundant life on Earth [Royer et al., 2007; Retallack, 2009]. CO2 has also been widely noted due to the fact that fossil fuel burning increases the air concentration of CO 2 and very likely contributes to global warming [IPCC, 2007]. The major processes regulating the air concentration of CO2 are related to carbon uptake in the planet's surface and carbon release from the surface into the atmosphere. In the preindustrial times after the last glaciation a global balance between carbon uptake and release resulted in a stable store of ca 280 ppmv CO2 in the atmosphere1. At present, the air CO2 concentration is more than 388 ppmv2, with a yearly release and removal of CO2 from the atmosphere corresponding to approximately 218 Gtons and 215 Gtons of carbon, respectively [Denman et al., 2007]. Fossil fuel burning and global land-use change account for 8 Gtons of the release-flows, while approximately 5 Gtons of the carbon uptake represents nature's feedback response to the increasing air CO2 concentration. The release flows are thus large enough to exceed the total uptake, and significantly increase the air concentration of CO2. 1. The present atmospheric CO2 content is higher than in the last 420 000 years [Petit et al., 1999], but still low - or much lower - than most time of the current Phanerozoic eon [Berner, 2006]. 2. 388ppm in the global CO2 trend data from August 2009. Websource: ftp://ftp.cmdl.noaa.gov/ccg/CO2/trends/CO2_mm_mlo.txt Doctoral thesis 2009 1 (28) Introduction J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden The continuously increasing levels of CO2 in the atmosphere have been well known since the 1960's [Keeling, 1960], and have not been much questioned, due to the fact that atmospheric CO2 is simple to measure. On the other hand, the possibility of significant climatic effects due to the CO2 increase have been strongly debated and are still questioned, although most data now indicate that the increasing atmospheric CO2 concentrations very likely contribute to increased air temperatures on Earth [IPCC, 2007]. The global carbon cycle is expected to respond to global warming by different feedback mechanisms, such as carbon storage release due to permafrost melting or changes in global respiration and photosynthesis when global vegetation zones are moving. But, although today’s knowledge clearly points out a great importance of the global carbon cycle, its response to warming is not easy to predict. Many of the processes transforming carbon within ecosystems are still poorly understood, resulting in still large uncertainties of the terrestrial carbon budgets [Janssens et al., 2003; Canadell et al., 2007; Heimann and Reichstein, 2008]. The role of lakes Due to the particular warming of the northern hemisphere predicted by IPCC [2007], carbon cycle studies in northern ecosystems are of great interest. The specific importance of northern lakes is related to the high abundance of lakes in the north [Downing et al., 2006]. Northern forests and undisturbed peatlands are generally regarded as sinks of CO2 removing CO2 from the atmosphere [Janssens et al., 2003]. Also lakes and streams were earlier regarded as sinks of CO2, but was later shown to be net heterotrophic instead of autotrophic, with a whole lake respiration of organic carbon that exceeds the CO2 uptake by the photosynthesis [del Giorgio et al., 1997]. The net release of CO2 to the atmosphere from inland waters thus contrast the general net uptake by the terrestrial biosphere [Heimann and Reichstein, 2008]. Globally, inland waters are estimated to make a net contribution of approximately 0.75 Gton carbon per year to the atmosphere [Cole et al., 2007]. Of these, about 0.15 Gtons represents emissions of CO2 from lakes [Cole et al., 1994]. The lake estimate is however likely underestimated, since only half of the global lake area was accounted for in the calculation [Downing et al., 2006]. Furthermore, CO2 emissions from lakes have mostly been estimated with quite simple models, in contrast to the still very few studies in which lake CO2 2 (28) Doctoral thesis 2009 J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Introduction emissions have been directly measured [Anderson et al., 1999; Eugster et al., 2003; Vesala et al., 2006; Paper III]. Taken together, the inland water carbon cycling is neither well known nor well integrated in the calculations of terrestrial carbon budgets [Cole et al., 2007]. Consequently many questions are raised related to how aquatic processes affect the landscape net ecosystem exchange of carbon. Better understanding of the inland water carbon cycling will not only improve the terrestrial carbon budgets. It will also benefit the management of inland waters, due to the great importance of terrestrial carbon for aquatic ecosystem dynamics [eg. Jansson et al., 2007]. Production of CO2 in lakes The production of CO2 in lakes is mainly a result of organism respiration of organic carbon either fixated by in-lake photosynthesis (autochthonous organic carbon) or coming in to the lake from the catchment (allochthonous organic carbon) [Cole et al., 1994; del Giorgio et al., 1997]. With increased allochthonous input the total community respiration can exceed the lake primary production, turning lakes net heterotrophic [Cole et al., 1994]. Significant importance of allochthonous organic carbon in aquatic food webs has been shown especially in humic waters where poor light climate and nutrient limitation favors microbial metabolism [Grey et al., 2001; Kritzberg et al., 2004; Karlsson et al., 2009]. A large part of the CO2 production in unproductive lakes is therefore a result of bacterial respiration of allochthonous organic carbon. The importance of this process is stressed by low growth efficiencies (<10%) of bacteria in unproductive lakes3. Production of CO2 is also related to photochemical mineralization of organic carbon, although the rapid light attenuation in most natural waters means that this process is generally not important for controlling the CO2 supersaturation [Sobek et al., 2003]. Microbial respiration processes in both pelagic and benthic habitats significantly contribute to the CO2 concentration of the lake water. Generally the pelagic contribution of CO2 has been reported to be larger [Pace and Prairie 2005], but with considerable variation and with few data from unproductive lakes. In sum, the net production of CO2 in lake water is a net result of the balance between photosynthesis and respiration of organic carbon in 3. A growth efficiency of 10% mean that 90% of the total carbon consumption is used for respiration (CO2-production). Doctoral thesis 2009 3 (28) Introduction J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden the different lake habitats. External inflow of CO2 may, additionally, increase the concentration [Jones et al., 2001; Huotari et al., 2009]. And furthermore, the in-lake CO2 balance is strongly influenced by the abiotic processes which determine the transport of CO2 within the water column and the exchange of CO2 across the lake surface [Eugster et al., 2003; Huotari et al., 2009]. Emission of CO2 from lakes The water column of net heterotrophic lakes become supersaturated with respect to CO2, which results in a net flux of CO 2 from the lake surface to the atmosphere [eg. Cole et al., 1994]. The mean emission from boreal Swedish lakes is calculated to be 79 mg C/m 2/d [Algesten et al., 2004]. Gas emissions from a water surface occur either by diffusion or the release of gas bubbles (ebullition). Due to the high water solubility of CO2 most of the CO2 emission can be expected to occur via diffusive fluxes, while CH4, which is less soluble, to a greater extent is released via ebullition [Casper et al., 2000; Huttunen et al., 2001; Poissant et al., 2007]. The direction and magnitude of the diffusive flux of CO 2 and other gases through the air-water interface are dependent on the concentration gradient between the air and the surface water. The magnitude of the flux depends also on the gas exchange coefficient, k, determined by the particular properties of the micro boundary layer between air and water [Liss and Slater, 1974; Cole and Caraco, 1998]. One widely used model for estimating CO2 emissions from lakes was developed by Cole and Caraco [1998], who measured different gas pathways and factors which characterized gaseous loss of SF6 in Mirror Lake (Hubbard Brook, USA). There are at least two main difficulties using models; to get accurate predictions of k, and to get representative samples on temporal and spatial scales. To solve the temporal problem, logger techniques can be applied [Sellers et al., 1995; Carignan, 1998; Huotari et al., 2009], but a reliable k is very difficult to obtain unless a lake-specific model calibration/validation is conducted. Another approach for measuring gas fluxes is to capture the flux in chambers floating on the lake surface [St Louis et al., 2000; Huttunen et al., 2003]. This method has the benefit of also capturing 4 (28) Doctoral thesis 2009 J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Introduction gas bubbles. However by putting chambers on the surface, the gas exchange coefficient will likely be altered in comparison to the natural state. Duchemin et al. [1999] found that the boundary layer method gave significantly lower fluxes than those obtained from floating chambers, but that both methods gave values within the same order of magnitude. A more recent study [Matthews et al., 2003] showed that fluxes measured from floating chambers are likely to be overestimates, at least in low wind environments. Direct measurements using the eddy covariance (EC) technique [Valentini, 2003], have been published from Williams lake (Minnesota, USA, 37 ha) [Anderson et al., 1999]; Toolik Lake (Alaska, USA, 150 ha) and Soppensee (Schweiz, 25 ha) [Eugster et al., 2003] and Lake Valkea Kotinen (Finland. 4.1 ha) [Vesala et al., 2006]. Williams Lake was monitored for about three weeks distributed over three years, and Toolik Lake and Soppensee for about three days in each lake. Lake Valkea-Kotinen was monitored during one ice-free season. The EC-technique is, in contrast to the boundary layer technique, a direct measurement of turbulent scalar flows such as CO 2 emissions. In principle, the vertical movement of the air is correlated with the concentration of a scalar (e.g. CO2) that occurs across a virtual surface at a certain distance above the lake surface [Baldocchi, 2003]. The resulting output is the flux in a specific area upwind of the measuring sensors, often referred to as the ‘footprint’ or the ‘source area’. Aims and outline of the thesis Carbon turnover in lakes has mostly been studied in North America and Northern Europe [Sobek et al., 2005]. This thesis follows this tradition, but focuses on the less studied high latitude lakes. The major aim of the thesis is to bring further knowledge about high latitude lakes, with emphasis on analysis of whole lake carbon turnover processes in one subalpine lake with short water retention time, and one boreal lake with long water retention time and an area large enough for EC-measurements in many wind directions. The whole lake approach used in the four research papers aims to (1) assess the relative importance of pelagic and benthic CO2 production processes (2) to apply and confirm the EC-technique for measurements of CO2 fluxes in the lake-atmosphere interface, and (3) to analyze the causes of the CO2 variation in the surface water. Doctoral thesis 2009 5 (28) Introduction J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden The questions addressed in the thesis is generally related to where in a lake CO2 is produced and how large the net lake ecosystem exchange of CO2 is. In Paper I the variation of surface water CO2 in the subarctic Lake Diktar-Erik is analyzed, while Paper II addresses the pelagic and benthic net production of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in the same lake. Paper III presents the result of ECmeasurements of the exchange of CO2 between the boreal Lake Merasjärvi and the atmosphere, while Paper IV analyzes the relationship between the surface water CO2 concentrations and variables related to hydrology, meteorology, water chemistry and the vertical thermal stratification of the lake water, in Lake Merasjärvi. 6 (28) Doctoral thesis 2009 J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Methods Methods With focus on carbon turnover processes, two lakes in northern Sweden (Figure 1) were intensively studied using both manual sampling and automated methods. Paper I and II present results based on data from the ice-free period in 2004 in the small subalpine Lake Diktar-Erik (8.8ha, 68°26'44"N, 18°36'18"E). Paper III and IV presents results from the larger Lake Merasjärvi (380ha, 67°33'00"N, 21°58'30"E), with data from the ice-free period in 2005. Some of the lake characteristics are compared in Table 1. 600 km Figure 1. Lake Diktar-Erik is located in the sub-alpine zone of the northern Scandes, while Lake Merasjärvi is located within the boreal forest zone of the north Swedish archean plains. Hydrology, meteorology and water chemistry In order to supply detailed data about hydrological, meteorological and chemical characteristics, logger systems were placed in the inlets Doctoral thesis 2009 7 (28) Methods J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden and outlets, and on the lakes. Campbell loggers, models CR10 or CR10X, were used for all data storage except for vertical temperature profiles which were logged with a set of Gemini TinyTag loggers at different depths in the deepest part of the lake. For methodological details about data logging see respective paper, or Paper IV which includes a multivariate analysis of most of the logged variables in Lake Merasjärvi. Carbon measurements Dissolved and particulate organic matter (DOC and POC) were sampled manually in the inlets and outlets and at different depths and locations in the lakes, and analyzed with standard methods (all four papers). A more detailed analysis of the low molecular weight compounds of the DOC was made in a study not included in the thesis [Jonsson et al., 2007] but discussed in Paper I. Inorganic carbon was analyzed both manually and with a logger system. With manual sampling (used in all four papers) both the total dissolved inorganic carbon concentration and the amount of dissolved CO2 were analyzed with infrared gas analyzers (IRGAs). The logger system only recorded dissolved CO2 in surface water (0.20.5m depth), but with 30 minute time-resolution (Paper I, III and IV). The carbon source of the DIC produced in Lake Diktar-Erik was analyzed with stable isotope analysis (Paper II). Net CO2 production In both lakes the net production of DIC was measured in the sediments and in the pelagic waters (Paper II and III). The pelagic net production of DIC was measured in incubation experiments as the difference in DIC concentration between the start of the experiment and after 48-72h. The incubations were made under in situ light and temperature conditions at the sampling depths in the lakes (Figure 2). Similarly, the benthic net production of DIC was measured as the difference in DIC concentration between start of the experiment and after 24 h incubation (in situ). Methodological details for both approaches are described in Paper II. 8 (28) Doctoral thesis 2009 J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Methods Figure 2. Preparation of an incubation tube for DIC-production measurements in Lake Merasjärvi. Anders Jonsson. (photo: J Åberg). Table 1. Characteristics of the two studied lakes and their catchments. Lake Diktar-Erik Lake Merasjärvi Elevationa (m) 375- ca 500 306- ca 500 Lake area (ha) 8.8 380 Max depth (m) 16.5 17 Mean depht (m) 5 5 0.45 19.61 37, 28, 11 275, 162, 118 DOC (mg/l) 5.3 (3.3 to 6.6) 6.2 (5.8 to 6.7) Secci depth (m) 4 3.2 Total N (µg/L) 200 113 6 6.6 Catchment area (km ) 6.1 59 Bedrock in catchment acidic acidic Major landcover in catchment Bare bedrock (49%) Boreal forest (51%) Mean annual air temperaturec -1°C -1°C 3 Volume (Mm ) Water renewal times (days) b Total P (µg/L) 2 a) above sea level (m) (from lake to top of the catchment) b) Three water retention times are given based on data from 2004 (Diktar-Erik) and in 2005 (Merasjärvi). The values are given in the following order: annual mean, mean for the ice-free period, mean for a theoretical epilimnion volume (0-5m depth) in July. c) average for the years 1969-1990 Doctoral thesis 2009 9 (28) Methods J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Emission of CO2 The diffusive fluxes of CO2 presented in Paper I and III were calculated using a boundary layer model [Cole and Caraco, 1998], where the k600 was recalculated to the actual temperature in the surface water, using the Schmidt number at the measured water temperature [Wanninkhof, 1992]. Air-borne flows of CO2 was measured over Lake Merasjärvi using an EC-system (Figure 3). The footprint area of the EC-system was estimated with Kljun’s webbased footprint calculator (http://footprint.kljun.net). The main sensors of the system used in Lake Merasjärvi were a sonic anemometer (Gill inc. model R3) and an open-path infrared gas analyzer (IRGA, Licor inc., model LI-7500), which had fast responses (20Hz sampling rates) in order to accurately record the turbulent movement of CO2 in the air. The raw EC-data were processed in the software Ecoflux 1.4 [Grelle and Lindroth, 1996], and thereafter quality filtered (see paper III). The performance of the EC-system was tested with a cross spectrum analysis and an energy balance closure calculation, and by comparing the EC-fluxes with the carbon budget of the lake. All three performance tests indicated that the quality filtered data were of good quality. For details about the processing and validation of the EC-data, see paper III. Statistics (selected approaches) Statistical methods found to be especially useful during the work with Paper I-IV, are listed in brief below: Sampling simulation (similar to the Monte-Carlo approach) was performed in Paper I. In order to calculate confidence intervals for averages based on differing number of samples, weighted standard deviations were used (Paper II). In paper IV the variables were many and dependent, which made the partial least squares regression (PLS) a good choice for surface water CO2 modeling. The statistical framework 'design of experiments' (DOE) was applied for making multiple linear regression (MLR) meta-models of the Ecoflux software during the preparations of Paper III. Fast fourier transformation (FFT) was used both for scanning of frequencies in time series (during the preparation of Paper IV) and for the cross spectrum analysis in Paper III. 10 (28) Doctoral thesis 2009 J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Methods Figure 3. The eddy covariance (EC) system in Lake Merasjärvi measured fluxes of CO2 between the lake and the atmosphere. The system was composed of four parts; a pole with sensors (left), a main raft (middle) and two solar panel rafts (right). The pole and the main raft (3×3 m) were placed approximately 350 m from the nearest shoreline. (photo: J. Åberg). Doctoral thesis 2009 11 (28) J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Results and discussion Results and discussion This chapter summarizes the findings in Paper I-IV, with concluding remarks in the last section of the chapter. Causes of CO2 variation in the surface water In Lake Diktar-Erik the surface water concentration of CO2 showed a large seasonal variation, with one especially large CO2 peak connected to a summer rain-storm that caused extreme water discharge. The high surface water CO2 concentrations were however not likely caused by increased inflow of CO 2, since the relationship between discharge and inlet water DIC was negative in Lake DiktarErik (Paper I). Increased concentrations of DOC and a higher bioavailability of organic matter, on the other hand, were linked to the CO2 increases (Paper I, [Jonsson et al., 2007]). The rate of DIC production needed to explain the large CO2 increases during the storm event was calculated to be 250 μg C/L/d, which was higher than the measured maximum DIC production rate in Lake DiktarErik (157 μg C/L/d, cf. Paper II), but comparable to mineralization rates in other similar systems [Graneli et al., 1996; Pace and Prairie, 2005]. The stratification depth in Lake Diktar-Erik probably also influenced the CO2 of the surface water by controlling upwelling of deep water CO2 and by regulation of the volume in which mineralization of DOC occurred. Also in Lake Merasjärvi the surface water concentration of CO2 varied considerably (Figure 4), but not in connection to discharge and DOC, due to the long water retention times. Instead the CO2 concentrations increased with increasing temperatures in the water column, and showed significant diurnal changes caused by diurnal variations in the depth of the mixed layer (Paper IV). High surface water CO2 concentrations were also clearly linked to upwelling of CO2 rich hypolimnetic water during periods with hypolimnion erosion. Emissions of CO2 have earlier been related to mixed layer dynamics by MacIntyre et al., [2001] and Eugster et al., [2003]. In summary, the levels of the surface water CO2 concentrations were linked to mineralization of organic carbon in both Lake Diktar-Erik and Lake Merasjärvi. In Lake Diktar-Erik, the large variation of organic carbon was the driver of the CO2 variation, while the low Doctoral thesis 2009 13 (28) Results and discussion J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden variation of DOC in Lake Merasjärvi highlighted the effects of temperature on respiration and the regulation of vertical transport caused by dynamics in the vertical thermal stratification. Internal CO2 production In both lake Merasjärvi and Lake Diktar-Erik the benthic habitats were net heterotrophic and showed little temporal variation in the net DIC production (Paper II and III). The pelagic water had a more variable net DIC production which clearly dominated over the benthic net DIC production in both lakes. During the season, 69% and 85% of benthic+pelagic DIC production occurred in the pelagic water of Lake Merasjärvi and Lake Diktar-Erik, respectively. These values agree well with the findings by den Heyer and Kalff, [1998], but differ from the conditions in clear-water lakes where the benthic habitat can be net autotrophic, while the pelagic water is still clearly net heterotrophic [Ask et al., 2009]. The net DIC production in Lake Diktar-Erik decreased with depth both in the pelagic water and in the sediments, and most of the net DIC production occurred in the upper water column (Paper II). A similar effect was seen in Lake Merasjärvi, where high temperatures of large water volumes was correlated to high CO 2 concentrations (Paper IV). Stable isotope data inferred that nearly 100% of the accumulated DIC in the hypolimnion of Lake Diktar-Erik was of allochthonous origin (Paper II). Similarly, 85% of accumulated DIC Figure 4. Selected logger data for Lake Merasjärvi, showing the dynamics of the surface water CO2 concentration in relation to the thermal stratification of the lake: A) the surface water CO2 concentration expressed as the concentration in excess of the atmospheric equilibrium (supersaturation). Black line = 24h (48pt) running average. B) the vertical water temperature profile where the contours represents water temperature (°C) in 0.5°C intervals. 14 (28) Doctoral thesis 2009 J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Results and discussion was indicated to have an allochthonous organic carbon source in the epilimnion. The pelagic DIC production, and most of the whole-lake net production of DIC, were thus the result of respiration of allochthonous organic carbon. Fluxes of CO2 to the air Lake Merasjärvi (380 ha) was the fifth lake in the world studied with the EC-technique. The system used had an open-path design which gave minimal flow distortions and required less processing of the data in comparison to the traditional closed-path systems [e.g. Song et al., 2005]. Best possible performance was indeed needed due to the low sensor height required to capture lake-only footprints (cf. Paper III). Paper III showed that measurements using the EC-technique had good quality and that the near 100% footprints were shorter than the fetch in all cases. The impact from surrounding forest on the flux was therefore expected to be minimal. The data from the EC-system were additionally in line with the independently calculated energy balance and an independent carbon budget, while the indirect estimates of CO2 fluxes with the boundary layer technique were not (Paper III). Consequently, the EC-measurements were considered to better than the other measurement-methods reflect actual exchange of CO2 between lake water and the atmosphere in Lake Merasjärvi. The summarized EC-flux of CO2 from Lake Merasjärvi during summer 2005 was two times higher than the fluxes predicted with models [Cole and Caraco, 1998; Wanninkhof, 1992]. By deriving the gas transfer rate, k, from the EC-data (Paper III) this difference could be related to underestimations made by the models during the most common wind speeds over Lake Merasjärvi (Figure 5). The correlation between the short-term EC-fluxes and the surface water CO2 concentrations was found to be low (R2=0.146) (Paper IV), which was to some extent counter-intuitive, considering the importance of the CO2 concentrations in the flux-models [e.g. Cole and Caraco, 1998]. On the other hand, the connection between flux and concentration is expected to be both positive and negative on a short-term time scale, since a high concentration promotes a high flux, while high fluxes also tend to decrease the CO2 concentration. Doctoral thesis 2009 15 (28) Results and discussion J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Figure 5. At common wind speeds the gas transfer rates derived from EC-data were found to be higher than predicted by models. The graph shows the normalized (to 20°C) median gas transfer rate of CO2 (k600) as a function of the wind speed at 10 m height (U10). Data were structured into bin classes of 1 m/s. The black circle represents the k600 at wind speed less than 1 m/s and was not accounted for in the regression. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval. Data are compared with boundary layer estimates based on the models presented by Cole and Caraco [1998] and Wanninkhof [1992]. Concluding remarks In both Lake Diktar-Erik and Lake Merasjärvi, the surface water CO2 variations were mainly related to a pelagic respiration of allochthous organic carbon, regulated by DOC input and whole lake water temperatures. Both lakes thus contributed to reduce the effect of carbon uptake by the land vegetation [cf. Cole et al., 2007]. Noticeably, the surface water CO2 concentration in Lake Merasjärvi was related to the whole lake water temperature, at the same time as the relationship between the surface water CO2 and the surface water temperature still was weak [cf. Sobek et al., 2005]. This indicates that predictions of surface water CO2 may benefit from including factors related to the whole water column dynamics rather than only factors in the surface water. The concentration of CO2 in the surface was highly dependent on diurnal and longer-term vertical water movements related to thermal 16 (28) Doctoral thesis 2009 J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Results and discussion stratification dynamics and hypolimnion erosion. This in combination with changes in respiration rates, by temperature changes or changing DOC levels, may contribute to large dynamics of the CO2 level in the surface of many lakes. In lakes with large CO2 variations, accurate estimates of the average CO2 concentration were shown to be dependent on a relatively intense sampling (Table 2 in Paper I). Conditions of hydrological stability or complete mixing of the water volume (especially in autumn), on the other hand, can be expected to decrease the CO2 variation allowing less intensive sampling (cf. Figure 1 in Paper IV). For CO2 flux calculations it must be pointed out that the short term variation of the EC-flux was not clearly related to the CO 2 concentration (Paper IV). Also, the two CO2 flux models clearly underestimated the gas transfer rate, k, at moderate wind speeds. These circumstances indicate that accurate estimates of k may be even more important for CO2 flux estimates than frequent sampling of CO2. In summary, the thesis bring more knowledge about carbon turnover processes in high latitude lakes, with applications related to future sampling and modeling of production and emission of CO2. The results show that the pelagic habitat can be very important for the inlake CO2 production. They also point out a need for further studies with direct (eddy covariance) measurements of emissions from lakes. A strong indication of the results is that CO2 concentrations and CO2 emissions change fast due to changes of the organic carbon loading and the temperature of the pelagic water. Doctoral thesis 2009 17 (28) J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Svensk sammanfattning Svensk sammanfattning De flesta sjöar släpper ut koldioxid (CO2) till luften i så pass stor mängd att även en liten tjärn bidrar med lika mycket CO 2 som en genomsnittlig svensk medborgare. Bidraget från världens trehundra miljoner sjöar är därför märkbart även i global skala. Än så länge bidrar dock sjöarnas koldioxidutsläpp sannolikt inte till ökad global uppvärmning. Detta kan förklaras med att sjöarnas kolomsättning och koldioxidutsläpp har varit en del i ett relativt stabilt kolkretslopp i tusentals år före den industriella revolutionen. Däremot saknas ännu mycket kunskap om sjöarnas roll i det globala kretsloppet av kol. Det finns exempelvis ännu många oklarheter kring hur sjöar producerar och släpper ut CO2, och inte minst hur sjöarnas koldioxidutsläpp förändras som följd av global uppvärmning. Sammantaget bidrar resultaten i denna avhandling till att ytterligare belysa kolomsättningen i sjöar. Delar av de intressanta resultaten är kopplade till användningen av en koldioxidlogger som med hög tidsupplösning visade hur koldioxidhalterna i ytvattnet varierade stort både på lång och kort sikt i både Diktar-Erik, 9 ha, och Merasjärvi, 380 ha (artikel I respektive IV). Med hjälp av inkubationer av sjövatten och efterföljande analyser visas i artikel II och III att större delen av koldioxiden producerades i vattenmassan och inte i sedimenten. Vidare redovisas i artikel IV att koldioxidproduktionen och ytvattnets halt av koldioxid ökade med ökad vattentemperatur, och att detta samband komplicerades av att vattenmassans värmeskiktningar styrde vid vilka tidpunkter som koldioxiden uppträdde i ytvattnet. Utsläppen av CO2 till atmosfären styrdes till stor del av vindhastigheten, vilket var i linje med vad tidigare studier visat. Däremot framkom att storleken på CO2-utsläppen i Merasjärvi var ungefär dubbelt så höga som de utsläpp som beräknats med de två vanligaste beräkningsmodellerna (Artikel III). Med början på nästa sida sammanfattas de fyra artiklarna var för sig. Doctoral thesis 2009 19 (28) Svensk sammanfattning J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Artikel I Variationer av koldioxid (Diktar-Erik) I studien framkom att koldioxidhalten i ytvattnet kan variera relativt mycket i en svensk fjällsjö. Artikeln diskuterar att koldioxidökningar inte kan förklaras med ett ökat vattenburet inflöde av CO2, eller annat oorganiskt kol, utan istället sannolikt beror på att främst bakterier ökar förbränningen av färskt organiskt material. Eftersom det underliggande kalla djupvattnet i sjön – hypolimnion – var rikt på oorganiskt kol diskuterades också möjligheten att detta förråd under vissa perioder kunde levera CO2 upp till ytan, och koncentrera effekten av kolförbränningen i sjön. Vinden diskuterades som en ytterligare viktig faktor som kan skapa både ökad koldioxidemission från sjöytan och ökad uppvällning av koldioxidrikt djupvatten. En viktig slutsats var att variationerna av CO2 i ytvattet visserligen påverkades av inflödet av löst kol, men att de ökade halterna av CO2 till största del måste härledas till interna transportprocesser och en mycket dynamisk intern koldioxidproduktion. Tack vare den höga tidsupplösningen på data, analyserades också hur provtagningsfrekvensen påverkar osäkerheten för mätningar av CO2 i ytvattnet. På grund av den stora variationen av CO2 under sommaren förbättras osäkerhetsmarginalen avsevärt vid provtagning varje vecka, jämfört med provtagning varje månad. Artikel II Intern produktion av koldioxid (Diktar-Erik) I Diktar-Erik skedde 85% av den totala koldioxidproduktionen i vattenmassan, och 15% i sedimenten. Att en stor del av koldioxiden producerades i vattenmassan kan tyckas förvånande, eftersom sedimenten innehåller mycket mer organismer som bryter ned organiskt material. Volymen sediment som bidrog till produktion av koldioxid var dock så liten i förhållande till den volym vatten som fanns i sjön att det slutliga resultatet ändå blev att vattenmassan bidrog med mest koldioxid. I brunvattensjöar med stor sedimentyta i förhållande till vattenmassa kan man däremot förvänta sig att bidraget från sedimenten får en mer framträdande roll för utsläppen av koldioxid (visas t.ex. i en studie av Åberg m.fl., [2004]). 20 (28) Doctoral thesis 2009 J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Svensk sammanfattning I djupvattnet i Diktar-Erik bildades i stort sett all CO2 genom förbränning av organiska ämnen med ett ursprung i vegetationen på land. Även i den övre delen av vattenmassan kom merparten av koldioxiden, ca 85%, från sådana organiska ämnen. Ekosystemet i sjön hade därmed en energitillförsel som till stor del var beroende av produktionen av biomassa på land. Genom att ett sådant sjöekosystem till större delen 'importerar' den energi som går in i basen av näringskedjan, betecknas det som 'netto-heterotroft', i motsats till exemplelvis de generellt sett 'netto-autotrofa' skogsekosystemen som både tillväxer i sin biomassa och 'exporterar' överskottet till sjöar och vattendrag. Artikel III Koldioxidflödet mellan sjö och atmosfär (Merasjärvi) Att mäta koldioxidutsläpp från sjöar är förknippat med vissa svårigheter: Först och främst är det är praktiskt taget omöjligt att fånga upp och mäta den gas som avgår från en normalstor sjö. Att däremot fånga upp gas från små ytor i små kammare går bättre, men med problemet att kamrarna riskerar att störa den naturliga gasutbytesprocessen, samt att mätningar på en procentuellt sett mycket liten yta av sjön inte nödvändigtsvis är representativa för hela sjön. Indirekta beräkningsmodeller för gasflöden mellan vatten och luft är också möjliga att använda, men dessa bygger på ett flertal förenklingar och antaganden som begränsar noggrannheten. Ett alternativ till både kammartekniker och beräkningsmodeller är den så kallade eddy-covariance (EC)-tekniken, som med hög tidsupplösning mäter flödena av koldioxid i luften över en relativt stor yta på sjön, utan att störa varken lokalklimat eller vind, samt med en mindre grad av förenkling jämfört med en indirekt beräkningsmodell. I artikeln redovisas resultat från EC-mätningar i sjön Merasjärvi, några mil söder om Vittangi i Norrbotten. EC-mätningarnas resultat jämförs med två vanliga indirekta beräkningsmodeller för gasflöden mellan vatten och luft. Jämförelsen visade att beräkningsmodellerna underskattade flödet av koldioxid till atmosfären med ungefär hälften. Detta något kontroversiella påstående ansågs dock vara välgrundat, eftersom EC-mätningarna hade kvalitetsgranskats på flera olika plan: dels kvalitetstestades alla data med ett urval av publicerade testmetoder, dels undersöktes systemets förmåga att mäta den virvelstorlek som förekom vid den specifika sjön. Vidare Doctoral thesis 2009 21 (28) Svensk sammanfattning J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden gjordes oberoende mätningar av sjöns kolbalans och energibalans i förhållande till EC-mätningarnas resultat, samt därtill beräkningar som visade att CO2-signalen som fångades av systemet inte kom från skogen utan enbart från sjön. Artikel IV Betydelsen av vattentemperatur och termisk skiktning för variationen av koldioxid i ytvattnet (Merasjärvi) I Merasjärvi användes strömsnåla loggrar för att med hög tidsupplösning mäta en mängd olika variabler, i luften ovanför sjön, i sjön, samt även i sjöns inlopp och utlopp. Även ytvattnets halt av koldioxid mättes med hög tidsupplösning. Sammanlagt kunde 26 variabler sammanställas och ställas i relation till ytvattnets halt av koldioxid. I själva analysen användes den statistiska metoden partial least squares regression (PLS), som är speciellt anpassad för analyser av många variabler. Resultaten av PLS-analyserna visade att koldioxidhalterna i ytvattnet var tydligast kopplade till vattentemperaturens variationer, samt till djupvariationer i skiktningarna mellan varmt och kallt vatten. Produktionen av koldioxid kunde därmed kopplas till att respirationen ökade med ökad temperatur, samt att värmeskiktningarnas variationer både påverkade respirationen och reglerade tillgången på CO2 i ytvattnet. Ett grunt epilimnion (det övre varma skiktet) hade i enlighet med detta, totalt sett en lägre tillförsel av CO2 via respiration, samtidigt som det genom att vara grunt förlorade mycket CO2 genom emission till atmosfären och genom fotosyntes. Avslutningsvis... Likt pusselbitar som läggs till ett ganska stort och svårt pussel bidrar resultaten i denna avhandling till att öka förståelsen om sjöars kolomsättning. Resultaten som presenteras indikerar t.ex. att sjöar som Diktar-Erik och Merasjärvi snabbt kan öka CO2-produktionen vid ökat inflöde av kol och vid ökad vattentemperatur. Trots det är det ännu för tidigt att utifrån enbart detta arbete dra generella slutsatser kring sjöars respons på t.ex. global uppvärmning. Resultatens kanske främsta betydelse är istället att de ökar den totala kunskapsmassan och lägger ytterligare grund för hur CO2-provtagning och CO2modellering – på bästa sätt – bör utföras i sjöar. 22 (28) Doctoral thesis 2009 J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Acknowledgments Acknowledgments First of all, I thank my wife and life companion, Susanne Åberg, for her support during my thesis work. Her earthy common sense and every day presence have helped me to stay balanced in a windy world. She also decided to move 720 km, to Vittangi, and live there together with me and our newborn baby during the summer of 2005. This, definitely played a crucial role for my commitment in Lake Merasjärvi, and for the results in Paper III and IV. Also on my top-list of supporters are my two daughters Noomi and Miriam. Their love and attitude to life is such a great inspiration. In the context of academic work I especially acknowledge their extraordinary insights in the noble art of thinking outside the box. Support of fundamental importance was also given by my two supervisors Mats Jansson and Anders Jonsson. They have been very professional and helpful, during all these years. They have also helped me much to understand the inside of the box. Without them this thesis would not have been possible to write. I also thank the following co-authors: Anders Lindroth for working with Paper III, and for making the 'flux-course' in Lund in 2003 such a great experience; Klockar Jenny Nääs for analysis of data, skillful fieldwork, and for philosophical conversations above the waters of Diktar-Erik and Merasjärvi; Jan Karlsson for being a great colleague and for an important contribution with the stable isotope analysis in Paper II. Thomas Westin in Abisko is acknowledged for field assistance of fundamental importance, and for skillful work with rafts and sampling equipment. I also thank Ingemar Bergström for sharing knowledge about Lake Merasjärvi and for his help with essential practicalities in the village of Merasjärvi. Financial support was provided by the Swedish Research Council, The Kempe Memorial Fund, Ebba and Sven Schwartz stiftelse, Stiftelsen Längmanska Kulturfonden, The Lars Hierta Memorial Foundation and Umeå University. Abisko Scientific Research Station contributed with parts of the meteorological data. The work was also a collaboration within the Nordic Centre for Studies of Ecosystem Carbon Exchange and its Interaction with the Climate System (NECC). Finally, a list of important persons that I wish to thank: My best friend and brother Andreas for his love, inspiring ideas and visits during fieldwork, and for introducing me to DOE and MLR-modeling; Anita and Torgny for their visits during field work and for day and night support in my life; my friend Anna who dropped by in Abisko; and Urban who also visited me in Abisko; Sven-Erik och Ingegerd for visits and great support; Anja, Christoffer and Andrea for their visits in Vittangi and Merasjärvi; the staff at In Situ Instruments/Flux Systems in Ockelbo, with special thanks to Micke for all help with software and hardware; the staff at Climate Impact Research Centre and the Abisko Scientific Research Station, with special thanks to Anne for being so hearty and kind; all people at EMG - past and present – with special thanks to 1) my former room mates Åsa and Mårten, 2) my limnologist colleagues Anki, Grete, Martin and Jenny, for help in many different ways, 3) teachers who improved my teaching: Tom, Hans, Tord, Jonatan, Rich, Johan and Lena, 4) the administrative staff, especially Kerstin K and Ingrid, and 5) my former 'kroken-neighbors' Matilda, Jan P, Veronica, Annika H and Carola. Och sedan till er andra: alla kära släktingar, vänner, grannar, kurskamrater, kollegor, flyktiga bekantskaper och så vidare, som jag inte nämnt. Tack för att ni finns! Jag önskar er all lycka! Kanske ses vi snart igen. Doctoral thesis 2009 23 (28) J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden References References Åberg, J., A. K. Bergström, G. Algesten, K. Söderback, and M. Jansson (2004), A comparison of the carbon balances of a natural lake (L. Örtrasket) and a hydroelectric reservoir (L. Skinnmuddselet) in northern Sweden, Water Research, 38(3), 531-538. Algesten, G., S. Sobek, A. K. Bergström, A. Ågren, L. J. Tranvik, and M. Jansson (2004), Role of lakes for organic carbon cycling in the boreal zone, Global Change Biology, 10(1), 141-147. Anderson, D. E., R. G. Striegl, D. I. Stannard, C. M. Michmerhuizen, T. A. McConnaughey, and J. W. LaBaugh (1999), Estimating lake-atmosphere CO2 exchange, Limnology and Oceanography, 44(4), 988-1001. Ask, J., J. Karlsson, L. Persson, P. Ask, P. Byström, and M. Jansson (2009), Wholelake estimates of carbon flux through algae and bacteria in benthic and pelagic habitats of clear-water lakes, Ecology, 90(7), 1923-1932. Baldocchi, D. D. (2003), Assessing the eddy covariance technique for evaluating carbon dioxide exchange rates of ecosystems: past, present and future, Global Change Biology, 9(4), 479-492. Berner, R. (2006), GEOCARBSULF: A combined model for Phanerozoic atmospheric O2 and CO2, Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta, 70(23), 5653-5664, doi:10.1016/j.gca.2005.11.032. Canadell, J. G., D. Pataki, R. Gifford, R. A. Houghton, Y. Lou, M. R. Raupach, P. Smith, and W. Steffen (2007), Saturation of the terrestrial carbon sink, in Terrestrial Ecosystems in a Changing World, edited by J. G. Canadell, D. Pataki, and L. Pitelka, pp. 59-58, Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg. Carignan, R. (1998), Automated determination of carbon dioxide, oxygen, and nitrogen partial pressures in surface waters, Limnology and Oceanography, 43(5), 969-975. Casper, P., S. C. Maberly, G. H. Hall, and B. J. Finlay (2000), Fluxes of methane and carbon dioxide from a small productive lake to the atmosphere, Biogeochemistry, 49(1), 1-19, doi:10.1023/A:1006269900174. Cole, J. J., and N. F. Caraco (1998), Atmospheric exchange of carbon dioxide in a low-wind oligotrophic lake measured by the addition of SF6, Limnology and Oceanography, 43(4), 647-656. Cole, J. J., N. F. Caraco, G. W. Kling, and T. K. Kratz (1994), Carbon-Dioxide Supersaturation in the Surface Waters of Lakes, Science, 265(5178), 15681570. Cole, J. J. et al. (2007), Plumbing the global carbon cycle: Integrating inland waters into the terrestrial carbon budget, Ecosystems, 10(1), 171-184, doi:10.1007/s10021-006-9013-8. Doctoral thesis 2009 25 (28) References J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Denman, K. L. et al. (2007), Couplings Between Changes in the Climate System and Biogeochemistry, edited by S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K. Averyt, M. Tignor, and H. Miller, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. Downing, J. A. et al. (2006), The global abundance and size distribution of lakes, ponds, and impoundments, Limnology and Oceanography, 51(5), 23882397. Duchemin, E., M. Lucotte, and R. Canuel (1999), Comparison of static chamber and thin boundary layer equation methods for measuring greenhouse gas emissions from large water bodies, Environmental Science & Technology, 33(2), 350-357. Eugster, W., G. Kling, T. Jonas, J. P. McFadden, A. Wuest, S. MacIntyre, and F. S. Chapin (2003), CO2 exchange between air and water in an Arctic Alaskan and midlatitude Swiss lake: Importance of convective mixing, Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres, 108(D12), 1-19. del Giorgio, P. A., J. J. Cole, and A. Cimbleris (1997), Respiration rates in bacteria exceed phytoplankton production in unproductive aquatic systems, Nature, 385(6612), 148-151. Graneli, W., M. Lindell, and L. Tranvik (1996), Photo-oxidative production of dissolved inorganic carbon in lakes of different humic content, Limnology and Oceanography, 41(4), 698-706. Grelle, A., and A. Lindroth (1996), Eddy-correlation system for long-term monitoring of fluxes of heat, water vapour and CO2, Global Change Biology, 2(3), 297-307. Grey, J., R. I. Jones, and D. Sleep (2001), Seasonal changes in the importance of the source of organic matter to the diet of zooplankton in Loch Ness, as indicated by stable isotope analysis, Limnology and Oceanography, 46(3), 505-513. Heimann, M., and M. Reichstein (2008), Terrestrial ecosystem carbon dynamics and climate feedbacks, Nature, 451(7176), 289-292, doi:10.1038/nature06591. den Heyer, C., and J. Kalff (1998), Organic matter mineralization rates in sediments: A within- and among-lake study, Limnology and Oceanography, 43(4), 695-705. Huotari, J., A. Ojala, E. Peltomaa, J. Pumpanen, P. Hari, and T. Vesala (2009), Temporal variations in surface water CO2 concentrations in a boreal humic lake based on high-frequency measurements, Boreal Environment Research, 14 (Suppl. A), 48-60. Huttunen, J. T., J. Alm, A. Liikanen, S. Juutinen, T. Larmola, T. Hammar, J. Silvola, and P. J. Martikainen (2003), Fluxes of methane, carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide in boreal lakes and potential anthropogenic effects on the aquatic greenhouse gas emissions, Chemosphere, 52(3), 609-621. 26 (28) Doctoral thesis 2009 J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden References Huttunen, J. T., K. M. Lappalainen, E. Saarijarvi, T. Vaisanen, and P. J. Martikainen (2001), A novel sediment gas sampler and a subsurface gas collector used for measurement of the ebullition of methane and carbon dioxide from a eutrophied lake, Science of the Total Environment, 266(13), 153-158. IPCC (2007), Climate Change 2007 - The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC, edited by S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K. Averyt, M. Tignor, and H. Miller, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. Janssens, I. A. et al. (2003), Europe's terrestrial biosphere absorbs 7 to 12% of European anthropogenic CO2 emissions, Science, 300(5625), 1538-1542. Jansson, M., L. Persson, A. M. D. Roos, R. I. Jones, and L. J. Tranvik (2007), Terrestrial carbon and intraspecific size-variation shape lake ecosystems, Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 22(6), 316-322, doi:10.1016/j.tree.2007.02.015. Jones, R. I., J. Grey, C. Quarmby, and D. Sleep (2001), Sources and fluxes of inorganic carbon in a deep, oligotrophic lake (Loch Ness, Scotland), Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 15(4), 863-870. Jonsson, A., L. Ström, and J. Åberg (2007), Composition and variations in the occurrence of dissolved free simple organic compounds of an unproductive lake ecosystem in northern Sweden, Biogeochemistry, 82(2), 153-163, doi:10.1007/s10533-006-9060-4. Karlsson, J., P. Byström, J. Ask, P. Ask, L. Persson, and M. Jansson (2009), Light limitation of nutrient-poor lake ecosystems, Nature, 460(7254), 506-U80, doi:10.1038/nature08179. Keeling, C. D. (1960), The Concentration and Isotopic Abundances of Carbon Dioxide in the Atmosphere, Tellus, 12, 200-203. Kritzberg, E. S., J. J. Cole, P. M. L., W. Granéli, and D. Bade (2004), Autochthonous versus allochthonous carbon sources to bacteria: Results from whole lake 13C addition experiments., Limnology and Oceanography, 49, 588-596. Liss, P. S., and P. G. Slater (1974), Flux of Gases across the Air-Sea Interface, Nature, 247, 181-184. MacIntyre, S., W. Eugster, and G. Kling (2001), The Critical Importance of Buoyancy Flux for Gas flux Across the Air-water Interface, in Gas Transfer at Water Surfaces, edited by M. A. Donelan, American Geophysical Union, Washington, D.C., USA. Matthews, C. J. D., V. L. St Louis, and R. H. Hesslein (2003), Comparison of three techniques used to measure diffusive gas exchange from sheltered aquatic surfaces, Environmental Science & Technology, 37(4), 772-780. Doctoral thesis 2009 27 (28) References J. Åberg Production and emission of CO2 in two unproductive lakes in northern Sweden Pace, M. L., and Y. T. Prairie (2005), Respiration in lakes, in Respiration in aquatic ecosystems, edited by P. A. del Giorgio and P. J. le B Williams, pp. 103-121, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Petit, J. R. et al. (1999), Climate and atmospheric history of the past 420,000 years from the Vostok ice core, Antarctica, Nature, 399(6735), 429-436. Poissant, L., P. Constant, M. Pilote, J. Canário, N. O'Driscoll, J. Ridal, and D. Lean (2007), The ebullition of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, methane, carbon dioxide and total gaseous mercury from the Cornwall Area of Concern, Science of The Total Environment, 381(1-3), 256-262, doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.03.029. Retallack, G. (2009), Greenhouse crises of the past 300 million years, Geological Society of America Bulletin, 121(9-10), 1441-1455, doi:10.1130/B26341.1. Royer, D., R. Berner, and J. Park (2007), Climate sensitivity constrained by CO2 concentrations over the past 420 million years, Nature, 446(7135), 530532, doi:10.1038/nature05699. Sellers, P., R. H. Hesslein, and C. A. Kelly (1995), Continuous Measurement of CO2 for Estimation of Air-Water Fluxes in Lakes - an in-Situ Technique, Limnology and Oceanography, 40(3), 575-581. Sobek, S., G. Algesten, A. K. Bergström, M. Jansson, and L. J. Tranvik (2003), The catchment and climate regulation of pCO2 in boreal lakes, Global Change Biology, 9(4), 630-641. Sobek, S., L. Tranvik, and J. J. Cole (2005), Temperature independence of carbon dioxide supersaturation in global lakes, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 19(2), doi:10.1029/2004GB002264. Song, X., G. Yu, Y. Liu, X. Sun, C. Ren, and X. Wen (2005), Comparison of flux measurement by open-path and close-path eddy covariance systems, Science in China Series D-Earth Sciences, 48, 74-84, doi:10.1360/05zd0007. St Louis, V. L., C. A. Kelly, E. Duchemin, J. W. M. Rudd, and D. M. Rosenberg (2000), Reservoir surfaces as sources of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere: A global estimate, Bioscience, 50(9), 766-775. Valentini, R. (2003), Fluxes of carbon, water and energy of European forests, Springer, Berlin. Wanninkhof, R. (1992), Relationship Between Wind-Speed and Gas-Exchange Over the Ocean, Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans, 97(C5), 7373-7382. Vesala, T., J. Huotari, U. Rannik, T. Suni, S. Smolander, A. Sogachev, S. Launiainen, and A. Ojala (2006), Eddy covariance measurements of carbon exchange and latent and sensible heat fluxes over a boreal lake for a full open-water period, Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres, 111(D11). 28 (28) Doctoral thesis 2009

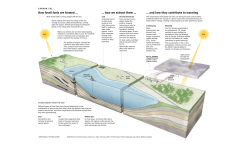

© Copyright 2026