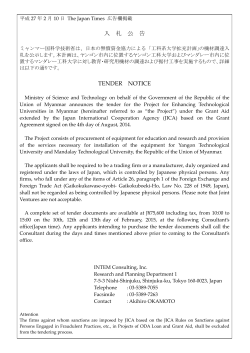

MYANMAR lNVESTMENTS lNTERNATlONAL LTD Leading the